It is crucial to address disparities and harmonise standards for all European cancer patients. An event at the European Parliament in Brussels, organised by the ABC Global Alliance focused on working rights and policies to protect patient autonomy

European politicians and policymakers were called on to implement consistent and flexible policies to enable cancer patients and cancer survivors to return to work, at an event at the European Parliament in Brussels organised last November by the ABC Global Alliance, the multistakeholder organisation for tackling the many issues faced by people with advanced breast cancer.

The meeting heard from a range of speakers about the increasing number of cancer survivors and in particular about those with advanced and metastatic breast cancer, as one of Europe’s most prevalent cancers; how employers should be helping people return to work or keeping their jobs; current legislation at European and national level; and various projects and resources that are informing policy and patient advocacy.

Lieve Wierinck, a Belgium MEP, and a cancer survivor, opened the meeting by emphasising that cancer has impact in the personal, social and working relationships of people, and that it is part of the big picture of addressing the cancer burden in Europe by providing more options for patients. It is crucial to address disparities and harmonise standards for all Europeans, she said. Many people want to continue working for financial security and to have a helpful distraction from their illness, and they should expect flexible support from their employers, as the effects of cancer treatment such as pain and fatigue can differ at various times.

Scale of the issue

Fatima Cardoso, a medical oncologist in Portugal and chair of the ABC Global Alliance, said that 1 in 8 to 10 women will have breast cancer in their lifetime, and the number of annual deaths will rise to more than 800,000 globally by 2030, about 43% more than the 560,000 deaths or so recorded in 2015. In Europe, there is a breast cancer diagnosis every 2.5 minutes and a death every 6.5 minutes. Cardoso explained that about a third of those diagnosed with early stage breast cancer will later relapse with a recurrence, and an important point that was made several times at the meeting is that cancer registries do not record the occurrence of recurrence. For this reason, the actual number of patients living with advanced cancer is currently unknown.

This makes it harder to convince policymakers about measures that need to be taken in areas such as workplace provision. Indeed, the meeting heard that an MEP, Deirdre Clune, has been pushing for EU funds for a pilot project to gather data on the employment status of people with metastatic cancer, with a focus on breast cancer patients, to assist in designing better policies and service provision.

Cardoso introduced the charter of the ABC Global Alliance, which among its 10 goals calls for doubling of median survival, increasing access to multidisciplinary care, improving communications and information, and reducing stigma. Last but by no means least among the goals is “help patients with ABC continue to work by implementing legislation that protects their rights to work and ensure flexible and accommodating workplace environments”, which given the rising incidence of breast cancer will mean more women (and some men) having to negotiate workplace arrangements (which of course also applies to those with other advanced cancers).

Working with employers and employees

Barbara Wilson, founder of Working With Cancer, which advises organisations and people on how to manage work during and after cancer treatment, had three key messages for the meeting:

- It is possible for most people with cancer, even those who are terminally ill, to continue to work (and she gave the recent example of a senior British civil servant who worked until a month of dying from lung cancer).

- Information must be given to employers and employees on what to expect during and after cancer treatment and how to manage at work. This means regular communication about the side-effects of treatment and having the flexibility to make adjustments for a gradual and successful return to work.

- There must be a consistent EU-wide framework that supports all people with cancer who face discrimination in the workplace. Wilson said that the UK Equality Act 2010, while not fully taken onboard by every employer, does a lot to protect cancer survivors against discrimination at work and to support their return to work, through for example, the requirement for employers to make reasonable workplace adjustments.

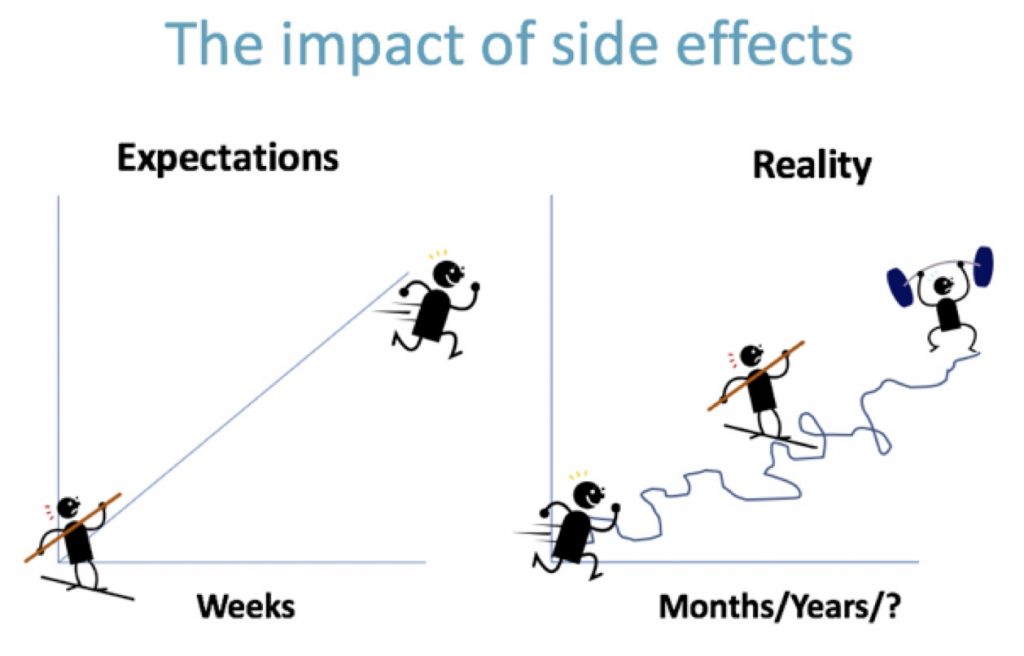

Work, she said, is an important part of one’s identity. It fulfils the need for social structure and provides financial stability, a sense of normality and of purpose. But treatment and medication can cause fatigue, cognitive dysfunction, pain and other symptoms, and the path to getting better is not smooth; there are good days and weeks, but also bad times, and getting back to “normal” is often not possible. Fundamentally it is about establishing a “new normal”, which might take months and sometimes years to achieve; and some things never entirely disappear, particularly the fear of recurrence. Cancer is life changing – physically and emotionally – it would be wrong to think otherwise.

Wilson said a key issue, therefore, in returning to work is the uncertainty of managing periods of illness and that the generic sickness policies of many employers do no not take this into account.

Employment/return to work issues facing people with ABC

Karen Benn, head of policy and public affairs at Europa Donna, the European Breast Cancer Coalition, gave a detailed account of EU and national legislation, and also presented the results of a Europa Donna survey of people with breast cancer about their experiences and support in their countries for employment and return to work.

The EU’s Employment Equality Framework Directive 2000 is the legislative framework that should protect people with both early and advanced cancer from discrimination. But it is an EU Directive and not an EU Regulation, and while it must go onto the statute of the EU member states, each country has the flexibility to define what constitutes disability, and therefore whether or not cancer fits their definition.

Some countries, such as the Nordic countries, Netherlands, Ireland, France, Belgium and the UK do give cancer patients the ability to register as disabled and therefore to benefit from this legislation for their working rights, among other things. However, in many European countries, formal protection is either non-existent or the situation is legally ambiguous, and there is no data on how many cancer patients return to work or how easy they find it to do so. There are also big disparities in how countries help people to return to work after long-term illness – here the Scandinavian countries are good, said Benn, offering every cancer survivor a return to work plan.

Europa Donna’s survey, which was completed at a training course for metastatic patient advocates, found that a majority of the 35 countries represented at the course do indeed have disability discrimination legislation that protects cancer patients, and some countries also have other legislation which protect people living with cancer from discrimination. A majority also said there is information on social security and welfare, and on leave of absence and return to work, and on working part time, although the latter is mostly dependent on the employer. Representatives also reported that pressure from employers and colleagues discourages return to work, and there is stigma and lack of awareness of living and working with cancer.

There is some movement at EU level. A report from the European Parliament, on pathways for the reintegration of workers recovering from injury and illness, now includes amendments on cancer. In May 2018, a group of MEPs led by Rory Palmer (UK) launched the European Dying to Work campaign, which aims to protect terminally ill workers from dismissal; as it stands, there are no specific protections for terminally ill employees.

Also in 2018, MEP Deirdre Clune (Ireland) proposed a pilot project to the European Commission on collecting data on the number of people with metastatic cancer in the workplace, using breast cancer as a model; however, this project has not yet been funded. The aim of the project is to assist in designing better policies and service provision.

Benn said that a positive step is that the European Network of Cancer Registries (ENCR), which focuses on finding ways to integrate data from Europe’s cancer registries, is now being run at the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre. This may lead to solutions on how to collect data on metastatic recurrences in breast and other cancers.

Costs and value in cancer care

Richard Sullivan, professor of cancer and global health at King’s College, London, provided high level context about health systems in Europe. He told attendees that there are big threats to achieving equitable care for breast cancer and other diseases – social inequalities, which are rising in Europe, and the impact of technology such as new drugs and imaging, which must be subject to guidelines and also have a healthcare workforce that can deliver appropriate care. Otherwise care will become ever more expensive, he said, noting that breast cancer and colorectal cancer, due to their incidence, are the two cancers that particularly determine economic burden and whether policy response can control costs.

Economic impact is framed by direct healthcare costs and informal costs, balanced against productivity losses – and the figures are substantial. In Europe, total costs for breast cancer are over e14 billion, made up of 43% healthcare, 22% informal care, and 35% productivity lost to mortality and morbidity. It was highlighted later in the meeting that productivity loss of people unable to work is one of the biggest concerns for employers, although these figures also show the sheer cost that advanced cancer has on societies as people are lost to the disease, and Sullivan noted that metastatic cancer is substantially more expensive to care for than early stage disease.

Reports and projects

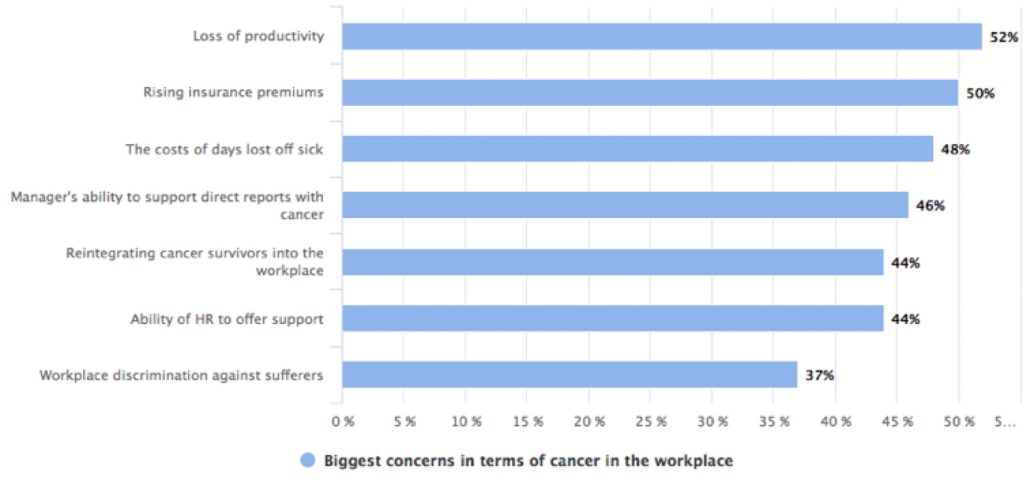

The productivity angle was picked up in the next segment of the meeting, which focused on reports. The first, Cancer in the Workplace, published by the Economist Intelligence Unit in collaboration with Bristol-Myers Squibb in 2016, assessed the challenges that cancer poses for employers and reported that loss in productivity of cancer survivors who were unable to return to paid work in the UK was £5.3 billion in 2010. In a survey, productivity loss was ranked highest among the concerns of employers, followed by rising insurance premiums and the cost of days off sick. Notably, high among the concerns was the ability of managers to support employees with cancer.

The report also surveyed employees and, encouragingly, when asked whether they feel confident that their employer would support them during the period of illness and up to 1 year thereafter, around 75% of respondents said that they would be fairly confident or very confident. This figure is higher among respondents in large companies. However, in the Q&A session later at the Brussels meeting, it was mentioned that in a survey in the Netherlands, it was small, family owned businesses that offered the most support, ahead of larger companies and the public sector.

Another project presented at Brussels was APolicy Roadmap on Addressing Metastatic Breast Cancer, sponsored by pharmaceutical company Lilly, which is raising awareness on clinical, economic and societal burden of metastatic breast cancer. Its recommendations include:

- Provide wider support systems and decision-making tools for metastatic breast cancer patients for coping with their diagnosis, handling their disease, managing their treatment’s side-effects, and organising their lives to allow for minimal disruption

- The European Commission should use the European Pillar of Social Rights as a policy framework to initiate adequate measures to ensure member states provide patients and informal carers with employment regulations that sufficiently protect their work-life balance

- Increase recognition of the role of informal carers and formalise their rights and access to available support systems.

Next up was Donatella Decise from Novartis, who updated attendees on the company’s Here & Now campaign for advanced breast cancer patients, which has evolved into My Time, Our Time. In 2019, said Decise, the campaign will conduct a similar survey to the one that launched Here & Now, to see what has changed for patients and carers in terms of the real-life impact of advanced breast cancer. In 2013, 40% of women in Europe with advanced breast cancer who were surveyed were working and of those, 25% worked full-time; 50% of patients had to make some change to their employment status, with the most common changes relating to a reduced working life.

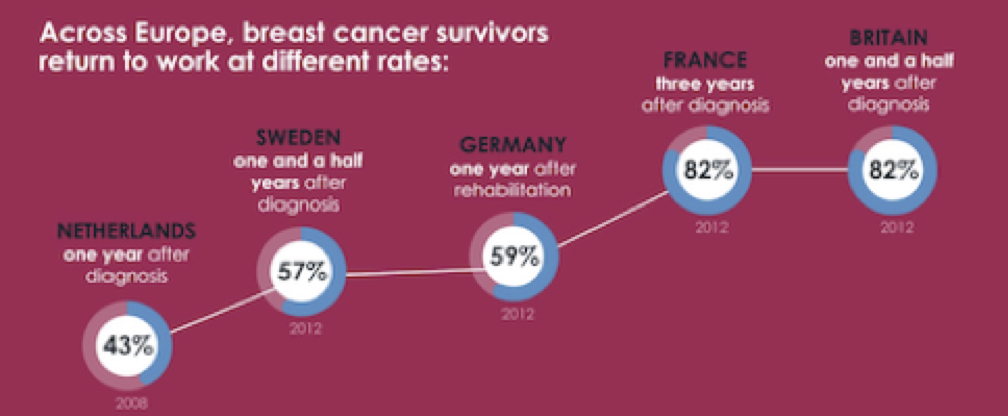

Lastly, Vincent Clay from Pfizer presented another report from the Economist Intelligence Unit, The road to a better normal: Breast cancer patients and survivors in the EU workforce. It notes:

- Societal and medical trends in Europe are intersecting to increase the number of breast cancer patients and survivors who are likely to want to work. In the past 15 years the proportion of European women aged 50-64 in employment has risen steadily, so that now a majority (59.6%) of that group are active in the labour force

- The rate at which breast cancer patients and survivors return to work is highly uneven, suggesting substantial room for improvement. National return-to-work rates for breast cancer patients and survivors who were in a job at the time of diagnosis ranged from 43% in the Netherlands to 82% in France

- Breast cancer and treatment side-effects make returning to work harder, but they are far from the only issues. Important non-medical barriers also impede a return to work, including lack of employer or colleague support, the extent to which work is physically demanding, and the level of education of the women involved. Such factors overlap to make specific populations vulnerable, particularly working-class women.

Q&A

The presentations covered a lot of ground, but attendees still found important points to make in the closing Q&A session:

- There are substantial numbers of self-employed women who do not have a formal workplace to return to, and face financial difficulties in particular. Younger women with breast cancer are likely to be most affected. Richard Sullivan said the only answer is to have mandatory insurance – voluntary schemes do not work

- The public sector should lead by example, but government employers are often the worst at supporting return to work

- People’s privacy must be respected – not all want their employers to know they have cancer, or how advanced it is. But employers cannot make adaptations if they do not have information. This also has implications for data collection, as some people will not be counted

- Organisations may respond better to incentives to adopt flexible policies rather than penalties. However, penalties have been given to companies, such as in the UK, where they have refused to make adjustments

- Fatima Cardoso suggested that legislation protecting the right to return to work part time or with flexible hours, coupled with financial support and/or tax exemption for employers who apply that legislation, could be a solution to protect both employees and employers

- Lieve Wierinck, in closing remarks, emphasised that financial support is crucial to enabling flexibility for employers that find it hard to support unpredictable patterns of absence for cancer patients. Replacement income from welfare that switches in on days when an employee cannot work would help solve this.

A more detailed report with a list of projects and documents is available on the ABC Global Alliance website