Studies indicate that a significant proportion of patients live to regret saying ‘yes’ to cancer treatments because of the impact on how they look, function or feel. Simon Crompton talks to patients and physicians about how oncologists and surgeons can minimise the number of their patients who end up feeling that way.

It was only once she had arrived at hospital, donned her surgical gown, and begun her pre-operative check that Joanna Moorhead acknowledged to herself and her surgeon what she had known all along. The surgery wasn’t going to go ahead. A mastectomy was not for her.

It was only once she had arrived at hospital, donned her surgical gown, and begun her pre-operative check that Joanna Moorhead acknowledged to herself and her surgeon what she had known all along. The surgery wasn’t going to go ahead. A mastectomy was not for her.

She’d been told a few weeks before that she had a 10-cm-long grade 2 invasive tumour. But the diagnosing surgeon had barely met her eye, and straight away started talking about mastectomy and reconstruction.

He seemed more keen to talk about surgery dates than to help her make sense of the news. Joanna, a journalist who wrote about her experiences for The Observer newspaper in the UK, knew the surgeon was not right for her. So she consulted another one, who talked, listened, and in the end agreed with Joanna. There were alternatives to mastectomy, and she could remove the tumour with a good margin.

“My breasts seemed such an important part of me,” says Joanna. “My big fear was that I’d be diminished by a mastectomy, that I’d never feel comfortable with myself again. I denied those feelings until the morning of the operation, when there was nowhere to hide.”

For others in the same circumstances, mastectomy might have been the correct decision. Sometimes making treatment choices for any kind of cancer isn’t just a matter of long-term disease outcome or even quality of life. It’s about making a choice that fits your personality – what’s important to you, what you do, how you see your body.

How well do clinicians help patients through this process, taking conversations beyond cool analysis of risk and benefit? Not very, according to Kari Tikkinen, consultant urologist and adjunct professor of clinical epidemiology at the University of Helsinki and Helsinki University Hospital.

“We should do shared decision-making better,” says Tikkinen, who has studied how men make choices in prostate cancer. “We not only need to provide evidence-based information, but also to let the patient talk and then really listen. Many clinicians will say they do this already, but they don’t. They do it too quickly. You can’t get the big picture of patient values, expectations and preferences in a short appointment.”

The research would seem to back him up. A study looking at breast cancer survivors found that almost 43% regretted some aspect of their treatment five years later – most often relating to primary surgery (PsychoOncol 2011, 20:506–16). Another study, looking at attitudes among long-term survivors of localised prostate cancer, found that 15 years after treatment, 15% of men regretted deciding on surgery for prostate cancer, and almost 17% regretted deciding on radiotherapy. Reasons for regret were dominated by sexual function problems (JCO 2017, 35:2306–14).

For some people, the most troublesome implications of treatment are about long-term effects on who they are and what their new body says about them. If these issues of self-image haven’t been addressed before decision-making, the real implications of treatment often only hit people once it’s too late.

A 2013 survey of 600 women who had been treated for breast cancer found that almost nine out of ten felt the disease and its treatment had had a negative impact on how they felt about their bodies, and only one in four felt they had been prepared for what was to come (bit.ly/BC_Self-Image).

Joanna Moorhead feels she had a close escape. She might never have had the courage to acknowledge her feelings and call off surgery at the last minute if, after the shock of diagnosis, she hadn’t taken time to research all her options and find a surgeon she could talk to.

“My big fear was that I’d be diminished by a mastectomy, that I’d never feel comfortable with myself again”

“I needed to get my head around the fact that I had cancer. Many of us have this deep-rooted feeling that cancer means we’re going to die, but I had to expunge that and recognise that early stage breast cancer is probably not something I’m going to die of.”

Joanna says a few short discussions with her new surgeon, Fiona, went a long way. “Fiona and I talked about how one size does not fit all. The risks I was happy to take would have been totally unpalatable to others. Good clinicians understand that there is no one way, but that it all comes down to how each individual accepts risk. My philosophy is that the best way to live life is to take risks, but I wouldn’t impose that on anyone else. It’s really about understanding someone’s inside track.”

“It might sound ambitious for surgeons to get to know their patients,” she says, “but I think they should all be competent at listening. If I could choose one skill in a surgeon it would be intuition every time.”

Getting it wrong

Women who choose mastectomy also have big decisions to make about reconstruction. But this too can feel rushed. Studies have shown that lack of discussion and information around reconstruction can lead to regret about decisions.

A recent study shows that those who choose reconstruction tend to overestimate how good and attractive it will make them feel, whereas those who decide against reconstruction can be pleasantly surprised at their wellbeing afterwards (JAMA Surg 2018, 153:e176112).

These findings mirror those of Laure Andrillon, a French journalist who investigated the experiences of women who had not had reconstruction for an article in the online magazine Slate (bit.ly/Beautiful-with-one-breast). The article went on to win a Cancer World Journalism Award.

In France, she says, it is assumed that women will want reconstruction and it is discussed at the first possible opportunity. “There’s an assumption that reconstruction is part of the treatment, which is in some ways good,” she says. “But it means some of them feel puzzled, guilty or alone if they don’t take that option… Talking to women who had not had reconstruction, they were quite surprised to find that it could be a positive experience.”

The way that options had been presented implied that reconstruction would bring a much better result for them psychologically. “The phrasing used is very important. Just the way physicians talk about the options shouldn’t imply that some are better than others.”

The wisdom of personal experience

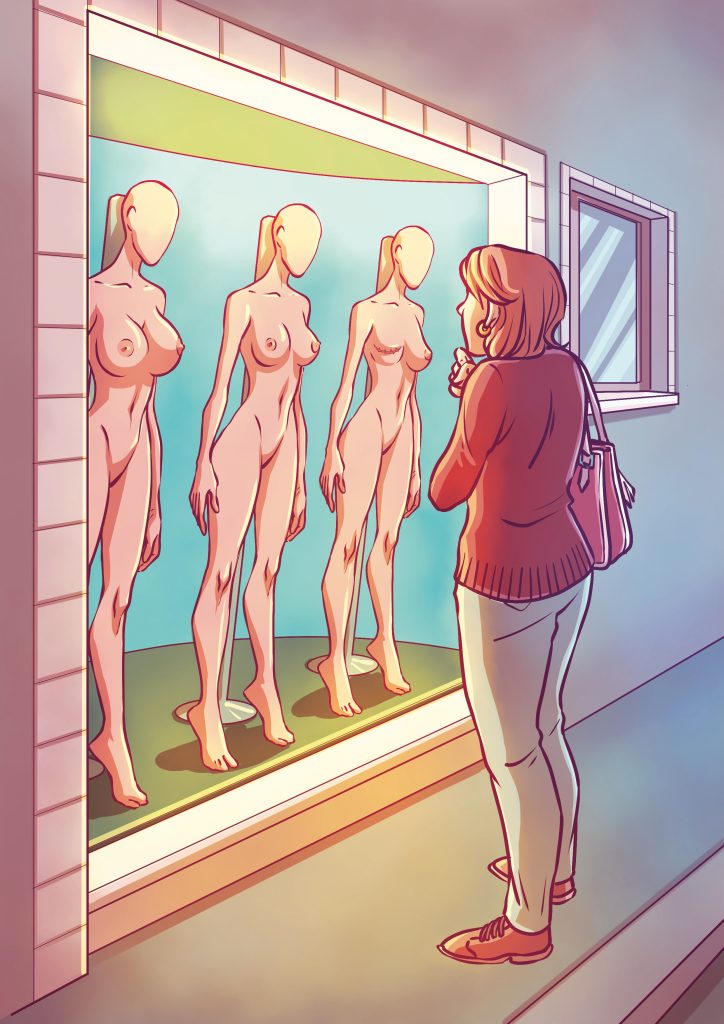

Before making decisions, women need to have a realistic picture of what they might look like – and feel like – after removal or reconstruction. Some breast surgeons have taken this need very seriously. When he was Director of the Breast Surgery Unit at the Maugeri Foundation in Pavia, Italy, breast surgeon Alberto Costa built up a group of ten women who had undergone different breast procedures who agreed to meet patients who were considering similar surgery.

“I’ve always been convinced that any explanation by a doctor or nurse – no matter how accurate – is not like contact with a person who has been through the same operation,” says Costa. “You need to see and physically feel what it means.”

“The women were available and accepted that there is no other way to understand what a reconstructed breast is. And this was really beautiful. We left these women in a room in peace, and the patient always came out saying now everything is clear. It was done through seeing and feeling.”

“You need to see and physically feel what it means… there is no other way to understand what a reconstructed breast is”

Such a service, he says, is easily organised by a surgeon or breast nurse. Breast cancer patient organisations can also help. The problem today is time. A system of 20-minute appointments doesn’t permit such flexibility or in-depth exploration, he fears.

Some French doctors, says Andrillon, also organise meetings with former patients. Others have books of photographs of women after surgery to help them understand how the body will look, and how they respond emotionally to that. “For the women I talked to, they see images as a very very important part of the decision,” she says.

Despite systems encouraging early decisions, there is actually plenty of time for women to make their mind up about what happens after cancer removal. “Many doctors have explained to me that usually it’s better to delay reconstruction anyway, so that women have time to think about it, read information, and discover their new body,” she says.

A hurried decision is rarely needed

Similar problems apply in prostate cancer, where clinicians and clinic systems often put unnecessary time pressure on patients. “At diagnosis, in at least 90% of cases it’s not an urgent situation and it doesn’t matter if you make the treatment decision today or next month,” says Kari Tikkinen.

There’s plenty of evidence that radical treatments such as prostatectomy and radiotherapy deserve unhurried consideration of personal implications: they can leave men with incontinence, bowel problems, impotence and a profoundly changed sense of self.

A 2017 review of studies concluded that men experience psychological and social changes after prostatectomy and that their perceptions of their masculinity are affected (Int J Nurs Stud 2017, 74:162–71). Men often described prostate surgery as “life-changing”, and although they recognised the trade-off between survival and postoperative complications, long-term effects such as erectile dysfunction often caused them more distress than the potential return of the disease itself.

Former patients have spoken of their regret. One who had his prostate removed soon after a cancer diagnosis said: “In hindsight, there are questions I wish I had asked. I should have spoken up before the surgery and discussed what I was feeling afterwards too.”

The problem, says Tikkinen, is not that radical curative options are wrong but that they are wrong for some people. And surgeons – and oncologists too – aren’t always suited to assessing this.

They tend to think in terms of abstract facts about survival and quality of life, but patients are often more interested in how everything fits in with their detailed personal agenda. “We tend to think about mortality, incontinence or erection, and actually patients think about whether they can do something – whether they can travel to a wedding that’s coming up, for example, or when they will be catheter free – which we might think of as quite secondary.”

Surgeons, oncologists and other specialists also tend to dictate decision-making by guiding patients towards their own specialty – even if it’s subconsciously. Studies have indicated that whether a prostate patient is referred first to an oncologist or a urologist has a major influence on their treatment decision. “We are all biased towards what we do,” says Tikkinen.

The answer, he says, is to be systematic in treatment decision-making, taking patients carefully through all the options, their risks and benefits, but also allowing them time and space to think and speak. He is an advocate of ‘encounter patient decision aids’ – tools such as infographics and bullet points that allow the clinician to go through vital information with the patient in a structured, considered way. For example, Tikkinen uses pictograms to show risks and benefits of different procedures.

Allow time for thorough discussion

A review of evidence conducted by Tikkinen and his team indicated that such aids help reduce regret about decisions made. But they need to be blended with time for discussion, and exploration of the patient’s outlook and values.

“I always ask questions like: ‘Are you the sort of person who likes to get rid of all kinds of risk?, or ‘Are you the sort of person who’s happy seeing what happens in life?’ They can give an indication, for example, of whether they are suited to active surveillance rather than active treatment.

“It can be challenging. You need time. In most systems you have around 20 minutes, but I’d say that a cancer decision-making appointment usually takes 45 minutes. That leaves me behind schedule but it’s crucial and you have to give it.”

The issues apply to every cancer, because the physical changes that come with any radical treatments inevitably change people’s sense of self. In colorectal cancer, for example, a stoma may be indicated for some patients – but this needs sensitive discussion. According to Stefan Gijssels, Executive Director of Digestive Cancers Europe and himself a colon cancer survivor, some older patients decide not to go through with stoma surgery even though that choice may have a significant impact on their life expectancy. “They don’t want to go through the burden of surgery or living with a stoma for the last years of their life,” he says. “This is a choice they should have, an alternative that should be discussed and offered.”

“In most systems you have around 20 minutes, but I’d say that a cancer decision-making appointment usually takes 45 minutes”

For anyone who needs a stoma as a result of gut surgery, there are difficult implications. Some may cope better than others. “Obviously it creates problems in terms of practical day-to-day life, sexual intimacy, self-image. I think these are manageable concerns once people have made their choice, often together with their partner. It’s also good to listen and discuss with other patients who have gone through it.

“I know of people who are quite satisfied after a stoma operation – for them it is better than they had anticipated. But you don’t tend to hear much from the ones who find it difficult, because those who are suffering don’t like to go into a public environment much.”

Gijssels believes that people are far more likely to be able to face life with a stoma if they are given plenty of time to talk to family, friends, surgeons, oncologists and even psycho-oncologists before the surgery. Many hospitals work with patient organisations so that people can find out first-hand from other patients about what it’s like to live with a stoma.

“You don’t tend to hear much from the ones who find it difficult because they don’t like to go into a public environment”

“The important question to ask, which is often forgotten by oncologists, is: ‘What do you expect from life?’ I know that’s really a philosophical question, but it’s about assessing what quality of life means. What do you like? How do you want to continue to live after surgery?”

What do patients want and expect?

Dora Constantinides from Nicosia, Cyprus, who had a colostomy when she was diagnosed with colorectal cancer at the age of 42, believes a lot has to do with a person’s outlook on life. “Cancer can act as a catalyst and bring out the best or worst in us.” Support from family and access to the right healthcare at the right time are also important.

At diagnosis, Dora was young, and very physically active with a young family, so she knew her sense of self would change. But talking to a doctor and stoma nurse about what life might be like after the operation helped her enormously. “They were considerate to ask where

I would like my stoma to be, and asked me how I wore my pants and where it would be convenient if I went swimming.”

Dora stresses the importance of patients knowing the positive and negative impacts of both temporary and permanent stomas. Doctors and former patients are a valuable source of information on both options, she said.

“From the beginning, my health professional team’s open communication and understanding facilitated the difficult journey to recovery and rehabilitation. They gave me an opportunity to make a choice, and every choice they gave was important – to feel you have a degree of control in your pathway. This kind of consideration helped me to accept my colostomy and come to terms with my new image.”

Dora went on to become a municipal councillor for Nicosia, representing the newly formed Green Party. She continues to live a busy and active life. She still swims and cycles, and is Head of Awareness at the Cyprus Association of Cancer Patients and Friends.

“There were changes of course, physically and psychologically. People always used to tell me what a nice figure I had and how beautiful I was, and I was an athlete. So it was a big change, but I felt okay after the initial shock of diagnosis – I’d been lucky enough to enjoy all that before, and I now felt there was more to me than the outside. I would look at myself as I was, and I accepted it. It’s a new part of me. Sharing everything with my family made the transition smoother.”

“It’s not the decision aids or the information package that matter. You have to listen to the patient and what’s useful for them”

Patient accounts are clear about what helps them accommodate the effects of their treatment into their daily lives. They are clear on what helps them make treatment decisions that suit their outlook on life and their sense of self. The question is, are clinicians and their organisations able to learn from those clear messages, and accommodate them into daily practice? Can hospital systems adapt to provide the time and access needed?

“We should be doing better shared decision-making,” says Tikkinen. “We are all so busy now everywhere in the world, and there’s an argument we need to rethink our clinical practice and give more time to help with decision-making. In the end, what really makes a difference is not the decision aids, it’s not the information package that matters. It’s the discussion in the office. You have to listen to the patient and what’s useful for them.”