People do better throughout their cancer journey when their physical, psychological and spiritual care needs are attended to. But how do we overcome entrenched mind sets that still resist integrating palliative and oncologic care?

Philip Larkin, associate professor in clinical nursing at University College, Dublin, began working as a palliative care specialist 25 years ago in rural West of Ireland. “What was called palliative care then was very much terminal care. We were called at the end of life, literally hours and in some cases minutes before death. It was not unknown to arrive at the house and find that the patient had already died.”

Philip Larkin, associate professor in clinical nursing at University College, Dublin, began working as a palliative care specialist 25 years ago in rural West of Ireland. “What was called palliative care then was very much terminal care. We were called at the end of life, literally hours and in some cases minutes before death. It was not unknown to arrive at the house and find that the patient had already died.”

Larkin contrasts his clinical work today at Our Lady’s Hospice and Care Services in Dublin with the marginal role that palliative care was afforded in a general hospital setting when he began. “We used to go into hospital predominantly to visit cancer patients. If the oncologist was on his ward round we were not allowed on the ward. He did not want to see us; he did not want to know. That has all changed.”

The value of palliative care early in the progression of cancer is becoming increasingly clear. The World Health Organization, and the European and US oncology societies ESMO and ASCO, all advocate its early introduction alongside treatments designed to increase survival.

In 2002, the WHO changed the definition of palliative care to “[care that] improves the quality of life of patients and families who face life-threatening illness, by providing pain and symptom relief, spiritual and psychosocial support, from diagnosis to the end of life”. The definition specifies that palliative care “is applicable early in the course of illness, in conjunction with other therapies that are intended to prolong life, such as chemotherapy or radiation therapy…”

Larkin strongly supported the change. “We started to see that the earlier involvement of palliative care in the overall care of certain groups of patients meant they would have a better outcome in terms of quality of life and the quality of their death. End of life care was still part of the spectrum, but we started to see much earlier referrals, seeing people not within hours of their death but probably within weeks or months.”

Research supports early intervention

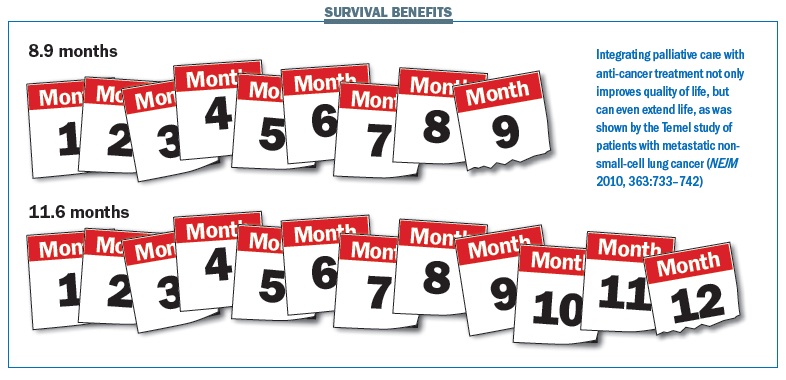

The most cited research comes from Jennifer Temel and colleagues at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, where 151 patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer were randomised to receive early palliative or standard oncological care (NEJM 2010, 363:733–742). Those who received early palliative care reported better quality of life, while fewer had depressive symptoms. The most startling finding was that the patients who received early palliative care survived more than two months longer on average than those on standard care (11.6 months vs 8.9 months), despite receiving less aggressive treatment.

Quality of life in the palliative care group actually improved over the trial period, comparable to improvements seen in patients who respond to cisplatin-based chemotherapy – “a formidable challenge,” Temel observed, “given the progressive nature of the illness.”

Temel speculated that poor quality of life and depression may themselves be factors leading to earlier death. It was also possible that integrating palliative and oncologic care ensured the best possible anticancer therapy, especially during the final months of life.

A larger study, conducted at Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, Ontario, was reported by Camilla Zimmermann and colleagues in the Lancet in February 2014. Oncology units were randomised to deliver early specialised palliative care or standard oncological care to 461 patients with advanced cancer. Specialist intervention included a multidisciplinary assessment, telephone contact from a palliative care nurse, a monthly outpatient clinic and a 24-hour on-call service. The trial measured change in quality of life, symptom control and satisfaction with care.

After three months, the change in scores from the baseline were significantly different between the two groups for Quality of Life at the End of Life (QUAL-E), and satisfaction with care (FAMCARE-P16), though not for symptom control (Edmonton Symptom Assessment System, ESAS) or for communication with healthcare providers (CARES-MIS). The change in the score for the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy- Spiritual Well-Being (FACIT-Sp) scale – which was the primary endpoint – was also better in patients receiving palliative care than the control group (an improvement of 1.60 compared to a deterioration of -2.00), but the result was not statistically significant. At four months, however, the improvements in the intervention group were significant on all scales except for communication with healthcare providers.

Both sets of researchers called for further studies to address these issues.

Helping people to live

Larkin points out that helping people live until they die has been a key principle of palliative care since it was expounded by Cicely Saunders, the founder of the palliative care movement. “We are there to help people to live as fully as they can within the confines of their illness, until natural death occurs.”

However, changing public and clinical perceptions is not so easy. ”We as practitioners can say, ‘This is who we are and this is what we do,’ but it is a bigger struggle to get people to understand that it is not just about the dying.”

Irene Higginson, director of the Cicely Saunders Institute and professor of palliative care at King’s College London, agrees that palliative care is about helping people to live. “I find the term ‘end of life care’ a bit misleading for people, and frightening. A lot of what we do is helping people live well despite a chronic or deteriorating illness or knowing they are dying. If you manage the symptoms, and help people to live as well as possible, when it comes to the end of life they have done the things they wanted to and spoken to the people they wanted to speak to.”

The question of whether someone is living with cancer or dying from it becomes less clear-cut as treatments extend life.

Roger Wilson, president of Sarcoma UK, was diagnosed with a soft tissue sarcoma in 1999 and with regional metastases in the following year. After surgery and chemotherapy, his surgeon told him that the cancer was not curable. “I suppose I have been in palliative care ever since,” he said. “I am now in year 15 and I still have periods with active disease, although none is actually detectable at the moment.”

Wilson, who was an independent producer and writer for the BBC before becoming ill, prefers the term ‘supportive care’ as descriptive of his own experience of episodes of acute treatment, followed by rehabilitation, physiotherapy, prosthetics care and psychological support.

After seven years of remission, a recurrence led to the amputation of the lower part of his left leg in 2007. Further recurrence was treated with surgery and radiotherapy in 2012. In 2013 his doctors discovered lung metastases. After two rounds of specialised surgery, using a laser knife, Wilson has since been tumour free – although not cured.

“The black and white line between curative and palliative care has got to go. We need to adopt a grey scale of curative therapy, supportive care and end of life care. We need to get the medical community on board. Being able to cross these grey boundaries is very important.

“Many patients who are not curable are receiving tyrosine kinase inhibitors and antibodies which can extend life and alleviate disease symptoms and side-effects. Their cancer is not terminal and may never become terminal. In this context, supportive care seems a very practical and sensible term.”

“We need to adopt a grey scale of curative therapy, supportive care and end of life care”

Alongside medical care for symptoms and side-effects and measures to prevent recurrence, Wilson lists psychological care, spiritual support and rehabilitation as key parts of supportive care. “Each patient has a set of needs which have to be connected to some form of service delivery attached to a menu.Patients need to be guided through the menu.”

Higginson agrees that the line between living with cancer and dying from cancer is ever more blurred. “For a lot of people who get cancer, the decision of whether it is curable or not curable is not so much one or the other. There is a grey area where you might be having life extension. Most advances in cancer treatment are not new cures, rather they discover life extension or put someone back into remission.”

Sometimes palliative care is given to resolve symptoms so patients can continue with potentially curative therapy. Severe mucositis, for instance, may need treating in patients with a haematological cancer. Even after a cure, palliative care may be appropriate. Higginson gives as an example someone who was successfully operated on for lung cancer but had a pre-existing chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. “They suddenly got very breathless. The problem was that surgery removed a big part of their lung, and because they had been sitting still they became debilitated. We are able to make them feel a lot better by treating their pre-existing lung disease and strengthening their muscles.”

Nathan Cherny, director of Cancer Pain and Palliative Medicine Services at Shaare Zedek Medical Center, Jerusalem, chaired the ESMO palliative care working group from 2008 until 2013 and has led efforts to integrate palliative care into oncology. He wishes change would happen more quickly. “Oncologists in general are very quick on the uptake of disease-modifying new innovations, but palliative care is one of those innovations where the oncology world in general has been fairly slow. There is a mind-set problem.”

Cherny argues that the treatment of patients with early-stage disease and a high possibility of cure is the easy part of cancer treatment. “The care of patients where there is no prospect of cure, integrating the best anti-cancer treatments with the best supportive and palliative care strategies, is much more difficult,” he says. “It requires personal and infrastructural resources, and is much more reliant on interdisciplinary cooperation. There is a need for a higher level of specialisation and expertise to assist in management and optimising the outcomes for these patients.”

“Palliative care is an innovation where the oncology world has been fairly slow. There is a mind-set problem”

Integrated care or separate specialty?

In Cherny’s Shaare Zedek Center, oncologists have palliative care training and the two services share a team of social workers, psychologists and spiritual care providers. They also share space in the day hospital, allowing patients to be screened by palliative care nurses with members of the multidisciplinary team on site to provide care in real time. “The patients who have got physical and psychological symptoms are the same patients who are presenting for chemotherapy or other treatments in the oncology day hospital,” says Cherny.

Most specialists agree on the need for a close working relationship, but believe that palliative care should remain as a distinct specialty. Philip Larkin says: “Palliative care has something unique to offer to the care of patients. In the same way as you have a gerontology team or an oncology team, you should have a palliative care team.”

Higginson says this is especially important as palliative care expands its role for patients with stroke or heart diseases or other conditions. “Increasingly, people who have cancer are also elderly and have arthritis or respiratory conditions or heart disease, because people who get cancer are living longer.” This older age group often misses out on palliative care, and extending provision is essential to avoid discrimination, she says.

However, Higginson also sees the benefits for patients of inviting palliative care specialists into the multidisciplinary team. “I bring something that a lot of other people in the room cannot bring: a wider view of the person’s other medical and health problems. Palliative care doctors are very good at looking at the whole person.

“I bring something that a lot of other people in the room cannot – a wider view of the person’s other health problems”

“Oncology is becoming more specialised as oncologists learn more and more about the specific management of groups of tumour cells. You expect the oncologist to have a certain level of core skills in palliative care, but it is not enough to say oncologists can do it themselves – that would imply that what we do in 10 years’ time will be the same as what we do now. Without a specialty, that is what you would get.”

Palliative care is increasingly seen as cost-effective. Xavier Gomez, who developed the Catalonia Project – a WHO demonstration project that provides inpatient, outpatient and community-based services for more than 23,000 patients across a region of 7.3 million people – says that the €52 million spent on delivering this type of care results in a net saving of €16.7 million by reducing use of acute and emergency beds.

Despite this growing consensus, there are huge gaps in care across Europe, and a need for further research. In 2010 the EU provided a grant worth €4 million to create a EURO IMPACT network in palliative care research, aimed at monitoring and improving palliative care. However, in 2011 Irene Higginson reported that just 0.2% of cancer research funding in the UK was being spent on researching palliative and end of life care.

Personalised care

For the palliative care specialist, ‘personalised care’ means much more than targeted drugs. In his work for ESMO, Cherny promotes a human approach to cancer care, where personalised medicine is about the person, not just about the science, and where people who cannot be cured are just as important as those who can. “There is a clear tendency to focus on the hope for a cure or of avoiding disease or early detection. The patients who are not going to be cured are in a sense like the ugly step-sister of cancer care.

“The term personalised medicine has essentially been hijacked to reflect the bio-science model of medical care, and I think we need to vigorously reclaim the social model. Targeted approaches are potentially important, but biological targeted therapeutics is only a part of personalised medicine.

Cherny argues that patients want to be seen and treated as more than the biology of their diseases. They want a commitment of care that is sensitive to their complex and often changing needs, and they want physicians who are confident, empathetic, humane, personal, forthright, respectful, and thorough.

“The term personalised medicine has been hijacked to reflect the bio-science model of medical care” “When patient needs are well tended and the patient is well cared for, the surviving family will never forget the experience. When they are neglected, it results in harm to the patient and long-term harm to the surviving families – it is never forgiven.”

Irene Higginson uses similar language: “I would really like to recapture person-centred and individualised care being about what the individual needs, with all their diseases, rather than it just being about their genetic make-up,” she says.

Higginson devised the Palliative Care Outcomes Scale (POS) to capture patient priorities and concerns, beyond what can be seen in blood tests and scans. “POS tells you what problems someone has, their symptoms, and what matters to them. It is a bit like having a scan for how the person is. We are finding for some diseases that POS is a better marker of deterioration than biological tests. How the person is feeling goes off first, before their blood tests reveal it.”

This suggests that patients should be given a greater role in assessing their own conditions. However, some clinicians are reluctant to let go of their high-tech security blanket. “That’s interesting,” observed one colleague, looking at her data. “It shows we need a better biomarker.”

Higginson sighs: “Why don’t we just get better at asking people what their symptoms are? We do all these fancy tests to look inside the body, when simply asking someone how they are tells you a lot.”

She feels that open-ended questions, such as “What is your main problem at the moment?”, give patients permission to raise issues they did not think the clinical team would want to know. “The job of the clinician is to read those things and try to respond,” she says. “We medics tend too much to go on knowing the answer rather than finding out where the person is.”

POS has identified neglected physical issues, including breathlessness, fatigue and weakness, as well as psychological issues, ranging from the need for information to depression, anxiety and fear, and family issues. “We do all these fancy tests to look inside the body, when simply asking someone how they are tells you a lot”

Supportive care or palliative care?

The language used to describe care and therapy reflects nuances and differences of approach. ESMO distinguishes between ‘supportive care’, to optimise comfort, function and social support at all stages of illness; ‘palliative care’, when cure is not possible; and ‘end of life care’, when death is imminent.

Roger Wilson would expand the definition of ‘supportive care’ to cover everything between a cure and end of life care, and drop the term ‘palliative care’ altogether. But Philip Larkin, while supportive of many of Wilson’s aims, is concerned that language should not confuse patients. “When people speak about the 50% of people they cannot cure as having supportive care, it is not entirely clear who delivers it and where palliative fits within that. We as professionals have a responsibility to be very clear about who we are and what we represent, so that patients don’t get misleading messages.”

He cites the case of a man with prostate cancer having radiotherapy to prevent spinal cord compression and reduce the risk of paralysis. “We know that the radiotherapy is simply to manage the condition. My concern is, does the patient understand that it is not curative? Is there something within them that is hoping that it is?”

Larkin teaches his students that honesty is the best policy, but says that does not mean it has to be brutal honesty. “The first few meetings can be quite gentle as you feel your way to figure out where people are at,” he suggests. “On a first visit a patient may say: ‘The doctor says you are a pain specialist’. I would say, ‘Yes, I am here to deal with your pain and I come from the palliative care team and we look after the symptoms.’ I am constantly checking in with people. Do they have a concept of what the palliative care team means?”

It’s not a question of having to talk about death and dying, he adds, but of being honest with patients about who you are and what your role is. “There may come a time when I need the patient to trust me; that won’t happen if he feels that I misled him at the beginning,” says Larkin.

End of life care

The fact that palliative care has a role to play in many stages of treatment should not disguise the fact that it still has a critical role when a patient is indeed dying.

Larkin challenges his palliative care students to think about what they can do for people who are dying that is different to any other practitioner. “What is your added value, because all nurses care for dying people?” They came to the conclusion that they have particular expertise in managing the transition between living and dying. “If a patient is given bad news about their illness, one of their questions they have in their head is ‘How long have I got?’ That is something that palliative care is very good at being able to manage in a sensitive way. They are able to lead patients and families very gently along a path of realisation.”

Larkin was amazed, when working in the West of Ireland, at how rural communities could read indicators. “There was myself and four women in the community team, and they used to say that if the women came you were doing fine, but if the man came you were on your way.”

They would watch who came to the door and what they brought with them, especially looking out for the syringe driver that allows a combination of drugs to be delivered subcutaneously (and is today used in the active management of symptoms). Larkin recalls: “The lay perception was that if the syringe driver came to someone’s house, it meant they would be going to a funeral in two or three days.”

Roger Wilson believes patients need support to address issues of life and death and their spiritual needs from an early stage. “It comes down, at the end of the day, to being able to answer for yourself some of the difficult questions like, ‘Why did I get this and what happens to me now? If I am going to die – what happens?’

“I am definitely not talking about religion. For people who have a religion, their minister can be a tremendous support and guide, but for those who do not have a religion or reject religion, there is still something needed – some form of existential counselling. ‘I am going to die – what happens?’”

At a critical moment, Wilson found his own guide. “I went through a very bad time psychologically when I had the first recurrence – the regional metastasis in 2000. I found a counsellor who was a Buddhist. I got a lot of very practical approaches to living and to dying.

“I have a very, very supportive partner. I could not imagine surviving without her. Your partner probably has a rougher journey in many respects. I go into hospital and lie on a couch and they stick needles in me or chop a bit out. There is a predetermined course and you get on with it. For her, there are all kinds of uncertainties during that 12 or 24 hours.”

He has had a long time to think about his own illness and his own mortality. “I feel very committed to talking as openly as I can. I want others to open up and to get their views in the whole context of supportive care. As far as I am concerned, I am not fighting cancer. I am not going to be a loser as and when I die. I am someone who hopefully will be remembered for having done his best to come through it, face it, and help other people through the challenges it presents.”