First he was a pupil, then he joined the faculty. Now Fedro Peccatori has taken charge of ESO’s entire educational programme, and he knows exactly where he wants to take it.

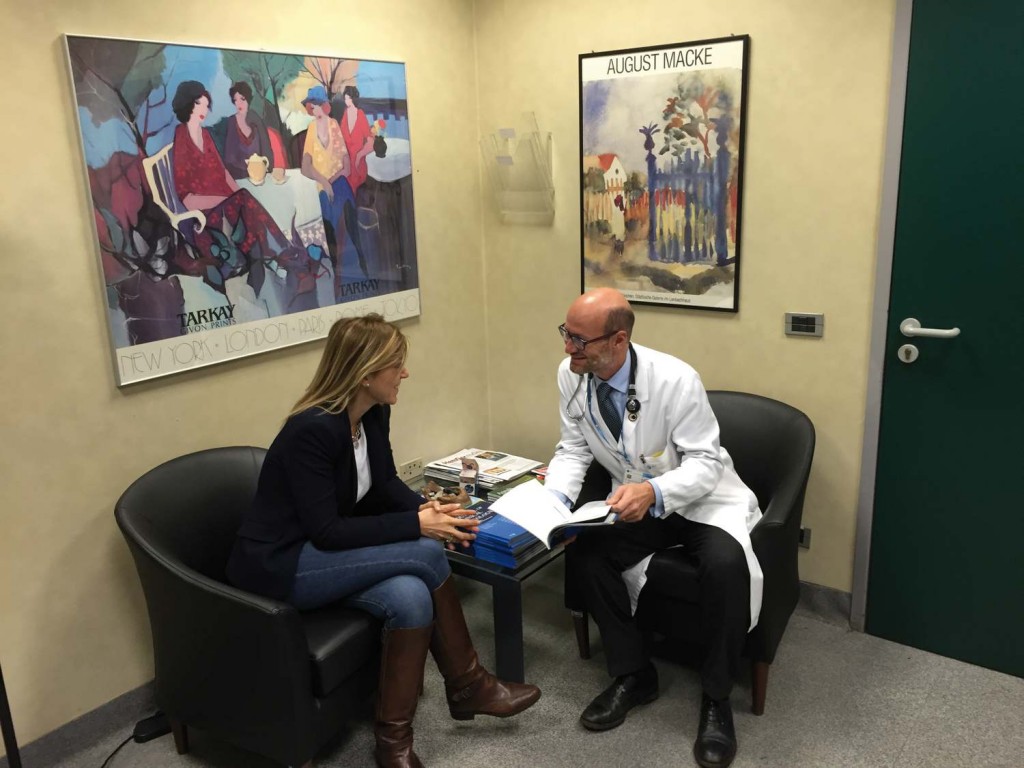

“There is no difference between my work at the hospital and my work at the European School of Oncology. In both cases it’s about finding the best way to treat patients.” This is how Fedro Peccatori, an expert in women’s cancers and fertility preservation at Milan’s European Institute of Oncology, interprets his new role as ESO’s Scientific Director, which he started this January.

His appointment puts him in charge of developing and directing the educational activities of the School, to further its mission of contributing through education to reducing the number of cancer deaths, and ensuring early diagnosis, optimal treatment and holistic patient care.

His mandate is to focus on the unique strengths of ESO’s style of teaching and to give special attention to covering topics and reaching young oncologists that hold no interest for other – predominantly commercial – training providers.

For Peccatori it is a welcome new challenge, but it also marks an important generational milestone for the School itself. His only two predecessors – Alberto Costa, and before him Umberto Veronesi – were both founding members of ESO. Peccatori is the product of its schooling.

A unique contribution

He takes charge at a time when ESO is no longer the sole provider of specialist oncology training in Europe, as it was when he was starting out. However, he is clear that there is nothing to rival the unique contribution the School continues to make. ESO is special, he says, because of its vocation, summed up in its motto ‘learning to care’, which puts patients at the centre. “We are not interested in simply teaching techniques, or in explaining what cancer is and how to treat it.”

Caring for patients has been an important driver for Peccatori throughout his career. But it was his love of research that first motivated him to specialise in gynaecological oncology after completing his medical degree at the University of Milan. “I spent my first year at the hospital without getting out of the lab: I barely saw a patient! I was working on the immunology of gynaecological tumours, particularly on ovarian cancer – a research area that is now very current, but was really pioneering at the time.”

Pathology held a particular fascination for Peccatori. “In my view, it was the best way to understand the roots of disease. Twenty-five years ago, cancer – and particularly women’s cancers – were in need of basic research.”

After one year on the lab benches, he returned to the wards: “I really enjoyed taking care of people and interacting with the patients, but my first interest in research never vanished,” he recalls. “I think that a good doctor needs to do both. Now we call it ‘translational research’, but in the ’80s there was no name for it.”

Peccatori completed his specialisation at the San Gerardo Hospital in Monza, north of Milan, and it was here that he was given a tip that was to change the course of his career. Costantino Mangioni, the professor he was working with, had strong connections with the Oncology Institute of Southern Switzerland, in Bellinzona, and advised Peccatori to spend a month there learning how to set up and conduct phase I and phase II trials, which were not being conducted anywhere in Italy at that time.

By chance, the Institute’s director, Franco Cavalli, was looking for someone to provide temporary cover for one of his assistants, who had been called up for army duty. “I was just married and had no salary from Italy, because the doctors in training weren’t paid at the time, so I was really happy to find a job!” he recalls with a smile.

In the end, he stayed at the Institute for almost two years, taking care of all kinds of cancer patients, in a working environment that was radically different from the one he had grown up with in Italy. “I was used to implementing decisions taken by my mentor, but here we were all expected to take responsibility for the care of the patients,” he recalls. “It was a great school, which strongly influenced the way I looked at the practice of medicine.”

It also taught him some hard truths about the nature of scientific progress. Invited to give a lecture on ovarian cancer, right at the start of his internship, Peccatori gave an enthusiastic account of the great results being obtained with cisplatin. “I called this therapeutic novelty ‘the paradigm of success’,” he recalls. Later that day, he was called on to care for a woman who was dying of a drug-resistant ovarian cancer. “I realised that an almost unbridgeable gap separates what we call a ‘great achievement’ in our peer-reviewed journals from what is a small improvement from the point of view of patients.”

Gender-specific oncology

On completing his PhD in gynaecological oncology Peccatori moved to Amsterdam’s Vrije Universiteit, to pursue his research interests at the Department of Anatomical Pathology. Focusing initially on cervical cancer, and on a model for a vaccine, he later moved on to researching the full spectrum of women’s cancers. “This is the root of my interest in what we call today ‘gender-specific oncology’.”

With the establishment of Milan’s European Institute of Oncology in 1994, he grasped the opportunity to return to Italy, and has remained there ever since. In his current role as director of the Fertility and Procreation in Cancer unit, he works with women with all kinds of cancers who want to preserve their chances of having children after treatment.

He also works with women who are diagnosed while pregnant, which, as he says, is a “very traumatic issue” that occurs in around 1 in every 1000 pregnancies. “Until a few years ago, the choice was often between saving the mother or the child. Now we can save both,” he says.

Doing the best for these patients requires the sort of expert multidisciplinary team they have at the European Institute, with a deep understanding of the effects of hormones on the tumour and on the development of the foetus, as well as the impact of chemotherapy side-effects. But much of this expertise is delivered remotely, as advice to doctors in hospitals closer to the woman’s home.

“We act as consultants for our colleagues working in other hospitals, to help them take the best decision on delicate issues such as the ideal gestational age to induce the delivery so as to be able to start treatments that are still potentially toxic for the foetus, such as trastuzumab or radiation therapy.” For the chemotherapy during pregnancy itself, his team decided, after long debate, that a cancer centre is not the best place for either mother or child, “so our patients are referred to outside maternity hospitals.”

The right setting

Finding the right setting for delivering care is an issue that preoccupies Peccatori beyond the specific situation of pregnant women. He argues that women’s cancers should be treated at specialist centres.

“Breast cancer and gynaecological cancers often have the same molecular basis. Even other kinds of cancer can be responsive to hormones when they occur in women, so you have to look at your patient as a complex and interrelated system,” he argues. “On the other hand, every woman with cancer has to face the same, very practical, problems: how to deal with family and work, with children, and with husbands who are not always ready to face such a difficult moment in their life as a couple. That’s why I think that women’s cancers should be treated all in the same place, with a multidisciplinary team that is able to tackle every aspect of the disease in a specific way.”

A new challenge

Peccatori is leaving none of this behind as he takes up his new role as ESO’s Scientific Director. Like his two predecessors, he will continue his clinical practice alongside his work directing the School’s educational activities.

It’s a lot for one person to take on. But then Peccatori is used to hard work and juggling home and work commitments. His typical day starts at 6.30 am, he bikes to work and returns home again in time to have supper with his wife and five children at 7.30 in the evening. “The lack of time for family life is probably my main regret,” he says.

In some ways he sees his appointment as simply an extension of a relationship with ESO that stretches back decades, first in his capacity as a student and later as part of the faculty. “ESO has been part of my professional life since the beginning of my career. I could say that it was part of my personal life too, as I spent my honeymoon in Amsterdam because there was an ESO masterclass in gynaecological oncology.”

The arrangement, he adds, worked well for everyone, as the young couple had no money at the time. “I went to the masterclass while my wife visited the city, then we spent some more days together at the end of course. We stayed at a very romantic location fronting onto the canals!”

His early experiences with ESO had both a European and an Italian flavour: “I remember the courses on breast cancer at Orta San Giulio, a small island in the middle of the Orta Lake, in Northern Italy. They were the best masterclasses for a young oncologist, and a truly new opportunity for attendants. We met people from all over Europe and beyond, and also the most important key opinion leaders in the field, building networks that are really useful for our professional life until now.”

Today, the training opportunities for young oncologists are more widespread, and Peccatori will be focusing ESO’s activities where they can have the greatest impact, particularly on aspects of oncology that are essential for patient care, but do not interest other education providers.

“There are areas where, without ESO, there would be no continuing education for oncologists. It’s not only a matter of income level or of organisation, but also economic interests. We can offer training in how to treat diseases that no pharmaceutical company would be interested in, because there are no drugs involved. I would say that pharmaceutical industries are our only real competitor in the educational programme, but they naturally focus on cancers that can be treated with their products, and in the same way in every country.”

ESO masterclasses, by contrast, are carefully tailored to fit the region where they take place. “It’s true that there is always a ‘best way’ to treat a cancer, but not every region has the same healthcare organisation or can afford the same treatments. We have to deal with these issues, which is why half the faculty at our events is always composed of local experts.”

ESO masterclasses, by contrast, are carefully tailored to fit the region where they take place. “It’s true that there is always a ‘best way’ to treat a cancer, but not every region has the same healthcare organisation or can afford the same treatments. We have to deal with these issues, which is why half the faculty at our events is always composed of local experts.”

It’s also why in recent years the School has increasingly taken a lead on the global policy agenda, through initiatives such as the World Oncology Forum, a series of policy conferences involving global experts, which Peccatori is particularly proud of. “We need a global cancer plan to fight the disease, especially now that we have tools like the HPV vaccine, which could really bridge the gap between richer and poorer countries,” he says.

“Prevention is very important, but we can also treat cancer patients and save lives with highly accessible low-cost drugs,” says Peccatori, pointing to studies that indicate that global deaths from breast cancer could be dramatically reduced if every country had access to 80% of the drugs on the WHO’s essential medicines list. “The same could be done for some paediatric cancers, like acute lymphoblastic leukaemia, which can be treated with a couple of very old drugs and better organisation of the health system,” he adds.

Promoting this low-cost, very international approach to cancer treatment will be an important focus for Peccatori as he takes over as Scientific

Director. “We can have a strong impact on healthcare systems even if we are not directly involved at a policy level, because we target the young generation of oncologists and even medical students. We can shape their views on what cancer is, how we should deal with it and what are the priorities.”

As he points out, this international perspective is nothing new for ESO – he was involved 20 years ago in the School’s Latin American programme. What has changed is the potential for delivering training at a global level, so upgrading ESO’s capacity to operate in the new virtual environment will be essential, he believes.

The School has made a good start, he says, with its e-grandrounds – the fortnightly webcasts it delivers live, accessible to participants the world over, who can ask questions and interact with the presenter in real time.

“But we need to improve online access to all our courses to allow more people to participate even when they cannot attend the workshop in person,” he says, adding that it is now possible to follow an online course on a smart phone “even in the most remote area of Africa.” That is the sort of reach ESO should now be seeking to achieve, he argues, “as is fitting in a globalised world.”

Meet the staff

Nobody can work alone. Like his predecessors, Fedro Peccatori relies on a team of people who ensure that the European School of Oncology can maintain the quality of its education and expand the involvement of oncologists across Europe and beyond.

“ESO has a very dedicated staff. It would be impossible to achieve the standards we do with-out their help,” he says. “I’m really happy to have them with me. I’m not leaving my job as a doctor and researcher, so I will need their support and professionalism.”From back to front, left to right: Dolores Knupfer – Eastern Europe and Balkan Region Programme and Lymphoma Programme and Events, Laura Richetti – Events, Gabriele Maggini – Communications, Luis Carvalho – Latin/American Programme, Fedro Peccatori – Scientific Director, Alberto Costa – CEO and Cancer World Editor.

Marina Fregonese – Rare Cancers programme, Corinne Hall – Editorial and Media Office and Clinical Training Centres Fellowship Programme, Lorena Camarini – Administration, Francesca Marangoni – Breast Cancer Programme, e-ESO, WOF and Events, Chatrina Melcher – Chief Operating Officer, Elena Fiore – Events, Alexandra Zampetti – Certificate of Competence in Breast Cancer and Events.

Not present: Daniela Mengato – SPCC, Eurasia Programme, Arab Countries Programme and Events, Paolo Gatti – Administration, Rita De Martini – Prostate Cancer Programme and Events.