At a time when the search for the ideal recipe of the most effective multidisciplinary approach to cancer care is still on, the life of millions of cancer patients around the world could be saved with a better organization of healthcare, devoting the scarce resources available in each local context to the most effective mixture of ingredients – from the most basic to the most advanced and expensive, from prevention to early diagnosis, to specialized therapies – without forgetting palliative care.

In setting the Agenda of sustainable development goals for the near future, the United Nations decided to aim at “reducing premature deaths due to incommunicable diseases by one third by the year 2030”. The exact path to reach that ambitious target is far from clear, but the World Health Organisation (WHO) and the European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO) are currently joining efforts to blaze a trail for cancer.

Correcting the extravagance of unrelated projects

Even just assessing how many doctors would be needed in a single country, compared to those that are available, is a much more complex task than it may seem at first glance. Such attempts are not new, of course: “We have attempted to outline a method which we hope will correct the extravagance resulting from the present series of unrelated projects, and weld these together into an integrated, orderly whole” read the “so-called Vorhees report” to the Hoover Commission, cited in an editorial opening the issue of the New England Journal of Medicine published on March 17, 1949 (N Engl J Med 1949; 240:440-441). “With such an organization, staffed with outstanding personnel, it should be possible to utilize our unequaled medical resources to the maximum, and by intelligent planning take steps which will make us a healthier and stronger nation”.

The editorialist commented: “If these proposals sound Utopian it means that they are being viewed from a parochial or traditional position. No resting place has been reached on the climb toward security and freedom. The sacrifices ahead may be greater than those behind”.

It was seventy years ago, and healthcare was quite different from what it is today. The question of how many doctors we actually need – and how many other health professionals and how much oncology services – is much more nuanced today, also depending on context: “In 2007, a study commissioned by the ASCO [the American Society of Clinical Oncology] Board of Directors predicted that the United States would likely face a shortfall of oncologists by 2020 partly because of an aging oncology workforce nearing retirement and a shrinking pool of new physicians seeking training in internal medicine (from which medical oncology draws its fellowship applicants). In response to these challenges, ASCO developed a workforce strategic plan that called for an increased use of nonphysician practitioners, increased coordination of care with nononcologists, research in care delivery efficiency, and increased support for fellowship program directors in their efforts to recruit and train new oncologists” wrote Roberto A. Leon-Ferre and Daniel G. Stover from the Mayo Clinic of Rochester, MN, and the Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center of Columbus, OH, in a recent editorial on the State of Cancer Care in America (Journal of Oncology Practice 14, no. 5 (May 1 2018) 277-280.). “Although more recent indicators have shown that changes implemented in the way cancer care is delivered seem to be easing the burden on practicing oncologists, the threat of a shortage persists”. Looking at the wider scenario beyond the rich United States – with their mostly private healthcare system – many aspects change, including the concept itself of shortage.

“How many doctors are enough doctors for a region?” the Canadian Medical Association Journal recently asked : “It’s complicated.”

How to deal with shortage in a wider perspective

In recent years, the “intelligent planning” invoked back in 1949 has taken the shape of national cancer control plans: “Over the past decade, the development and implementation of comprehensive, evidence-based, resourced plans has been repeatedly emphasised as a crucial step for countries to translate commitments related to non-communicable diseases (NCDs) into action” write Yannick Romero from the Union for International Cancer Control in Geneva, and colleagues, in a review article realized by the joint efforts of WHO, UICC, NCI, ESMO, including the contribution of the ICCP partnership published in The Lancet Oncology (The Lancet Oncology 2018, 19; 10: PE546-E555). “The Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of NCDs urges governments to set national targets for 2025 and to develop country-level NCD plans to achieve these targets”.

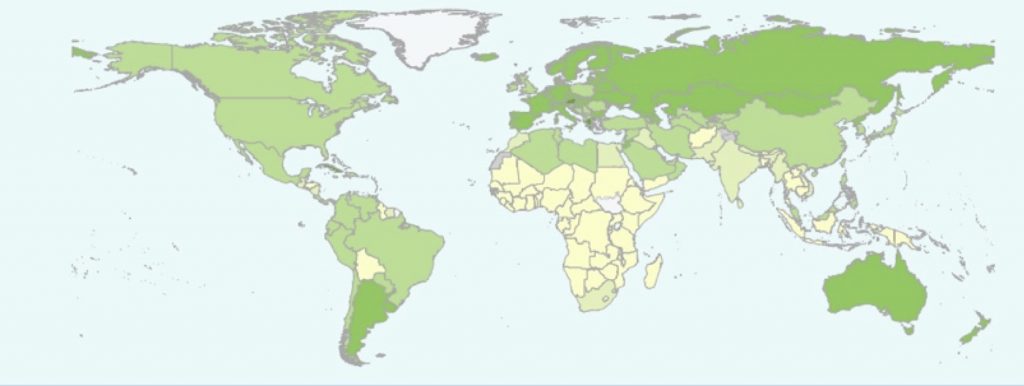

According to WHO estimates, the number of countries with a plan for non-communicable diseases inclusive of cancer, or a specific plan for cancer grew from 48% in 2000, to 87% in 2015. Still, a relevant part of those plans remains on paper: “The results show progress in the development of cancer plans, as well as in the inclusion of stakeholders in plan development, but little evidence of their implementation” Romero and colleagues write. “Areas of continued unmet need include setting of realistic priorities, specification of programmes for cancer management, allocation of appropriate budgets, monitoring and evaluation of plan implementation, promotion of research, and strengthening of information systems. We found that countries with a non-communicable disease (NCD) plan but no national cancer control plan (NCCP) were less likely than countries with an NCCP and NCP plan or an NCCP only to have comprehensive, coherent, or consistent plans. As countries move towards universal health coverage, greater emphasis is needed on developing NCCPs that are evidence based, financed, and implemented to ensure translation into action”.

The WHO-ESMO workforce survey

The review is part of the wider effort by WHO and ESMO that was illustrated last October at the ESMO annual meeting in Munich by André Ilbawi and Dario Trapani, who also co-authored the Lancet Oncology review: “It was a first taste of what will come” said Trapani, a medical oncologist from University of Milan and European Institute of Oncology and a consultant for WHO.

While it may be useful for research purposes to adopt a reference parameter for the number of cancer patients an oncologist can care for “one size does not fit all”, he explained. Not only the number of providers, but their level of specialization, organization and geographic distribution can have a strong impact on the quality of care. The infrastructure for training existing health professionals and to recruit and train new ones can also make a difference.

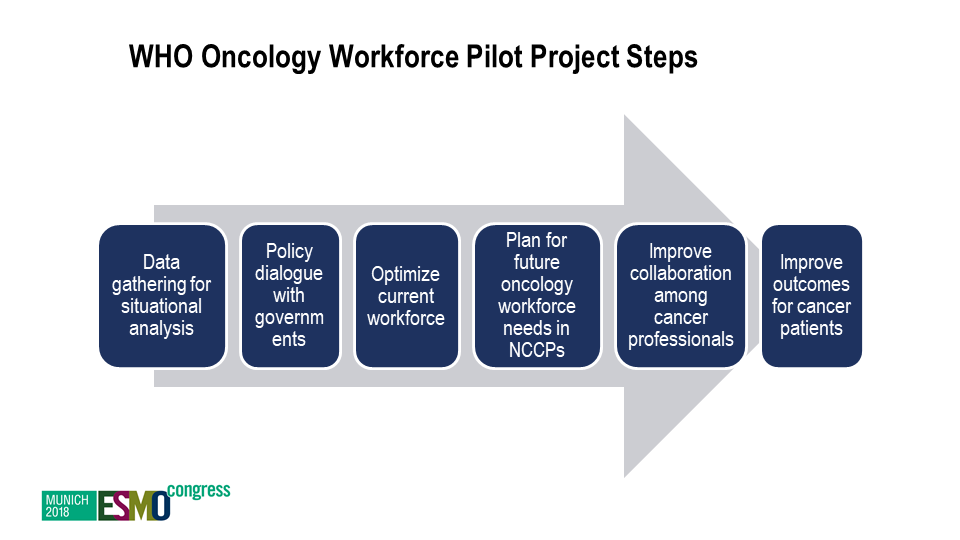

“A strategy without a plan is just a dream” Trapani said. “In setting goals, one must always tailor cancer control planning and workforce to the specific epidemiologic burden and health system capacity in each country”. In order to make the best use in practice of evidence-based, effective – and especially cost-effective – interventions, the pilot project the team is working on has devised six steps (see image below), that are currently the subject of a consultation with stakeholders from all over the world.

ESMO Congress, Munich 2018, presenter: Trapani D.

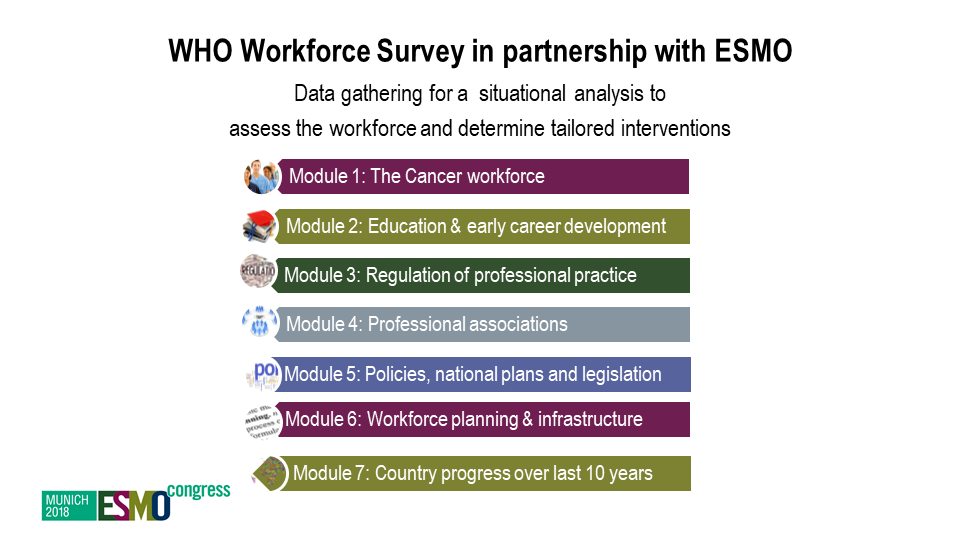

ESMO Congress, Munich 2018, presenter: Trapani D.

ESMO Congress, Munich 2018, presenter: Trapani D.

“The final tool will be the result of the work that we started in consultation with stakeholders at the regional and national level, with a process that will likely take several months and will also involve doctors from other specialty areas, as well as public health experts, epidemiologists, social scientists and civil society.” Trapani said.

The ultimate goal is to help decision makers to identify the priorities for their country and the most effective interventions that each context can sustain to assure short-term, mid-term and long-term lasting results in the fight against cancer.