She’s an internationalist, she believes in quality control and she’s not afraid of a bit of friction. Who better, then, to lead the project to define standards for Europe’s cancer centres and sort the centres that meet them from those that need to do better?

In Europe, if a hospital chooses to call itself a comprehensive cancer centre – either as a standalone oncology facility or a department within a general hospital – it is free to do so in most countries. Like other terms that convey quality and authority, such as ‘university hospital’ or ‘institute’, the public might assume that rigorous standards are applied by authorities to guarantee that status. But while there will almost certainly be many general hospital regulations about issues such as infection control, waste management and radiation exposure, patients would be hard pushed to find out just how good their cancer care is, or how much a centre is contributing to education and research.

“It’s not enough for a cancer hospital simply to say they are one of the top centres – they need to show they are,” says Mahasti Saghatchian, chair of the accreditation and designation group at the Organisation of European Cancer Institutes (OECI). “Just because a centre has many top oncologists does not automatically mean that patients are always getting the best treatments, or that they are participating as well as they could be in research programmes. Among the key aims of the OECI accreditation project is for centres to benchmark themselves against others and address weaknesses, and also to recognise where they can work together in research by building trust in their capabilities. And not least we hope it will also be a sign of trust for funders.”

As Saghatchian acknowledges, the accreditation tool for cancer centres was some time in gestation – it was six years in preparation before launching in 2008, and the first round of centres finally received accreditation in 2010. A further aim – that of designation – has been added to categorise locations as a unit, centre, research centre or comprehensive centre.

Founded in 1979, the OECI has been around a long time, but it had mainly been a relatively informal networking group for cancer centre directors in western and eastern Europe, says Saghatchian. “That changed when, in 2000, Ulrik Ringborg of the Karolinska in Stockholm, and Thomas Tursz, then director of the Institut Gustave Roussy in Villejuif, Paris, became OECI presidents and developed a vision for comprehensive cancer centres in Europe, in particular to integrate research with care and develop translational research networks.”

The accreditation project is part of this vision, which is similar to the comprehensive cancer centre structure in the US, but with more of a focus on all aspects of cancer management rather than a research network. But, as with any new measure, it has taken a lot of ‘selling’, particularly as there is a substantial commitment in time and fees. “It’s certainly been one of the most controversial projects I’ve been involved with in oncology,” says Saghatchian. And the OECI has had to find the initial resources to develop the standard, recruit auditors and so on, before fees from centres can make the programme self-funding.

“What has really helped get it off the ground is its incorporation as a work package in the EurocanPlatform, the EC-funded 7th Framework Programme project that aims to unite 28 European institutes in a translational research effort,” says Saghatchian. “It’s one of the commission’s networks of excellence for research and we managed to get accreditation in, very much as a cherry on the cake – and all the participating centres will also have to undergo the audit to take part in Eurocan.”

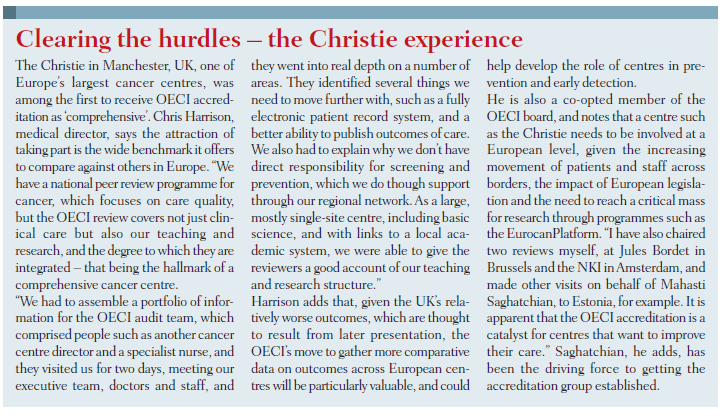

Not all the participants in Eurocan are hospitals – some are research institutes – but three of the first six OECI accredited centres are Eurocan members, namely the Netherlands Cancer Institute (NKI), the Christie in Manchester, and Valencia’s cancer centre (the other three are the Portuguese oncology institutes in Lisbon, Porto and Coimbra). Other centres are in peer review, and applications are pending for a major expansion, including heavyweights such as the Institut Gustave Roussy (IGR) (Saghatchian’s own employer), King’s Health Partners in London, Cambridge Cancer Centre, Institut Curie in Paris and the German Cancer Research Centre (DKFZ) in Heidelberg.

But what could mark a major breakthrough is a decision by Italy’s ministry of health to fund all ten of the country’s comprehensive cancer centres to go through accreditation. “We are starting to see governments and health ministries interested in the project. If they want to accredit their oncology effort, say as part of a national cancer plan, the OECI is the only international organisation able to do it,” says Saghatchian.

As she adds, the OECI and EurocanPlatform are also now partners in the second European Forum on Oncology, taking place in May in Berlin, where a key aim is to discuss the ‘bottom up’ structural reforms that the OECI is promoting in European oncology, including a workshop on ‘organisational concepts for comprehensive cancer centres’.

Although much of the initial impetus for the accreditation is coming from the translational research side, Saghatchian stresses that the role of cancer centres in all aspects of health improvement through oncology is very much part of the vision. Clinical care and infrastructure have as much weighting as research in the standard, which itself is not set in stone – it is currently being revised to focus on factors that can really differentiate practice. In any case, as Saghatchian adds, accreditation only lasts four years, after which any centre must go through the process again.

Clinical care and infrastructure have as much weighting as research in the standard

There are now moves to extend the project as an ‘umbrella’ to include accreditation for specific cancer centre departments such as breast units (where there is progress on a pan-European scheme for certification from EUSOMA and other parties), and also prostate cancer care, where there is currently very little to speak of in comparative tools. “We are discussing the idea of adding prostate units as an annexe to the OECI tool, which would take probably an extra day in the review process to carry out,” she says. “But it’s important to note that we are not going to duplicate professional guidelines, such as how to carry out surgery or apply systemic therapy. We are taking a global view of a centre and its activities, resources and outcomes.”

The accreditation work is one part of Saghatchian’s role at IGR, where she carries out two jobs: executive in charge of international and European affairs, and a medical oncologist in the breast cancer unit. It’s more or less an equal split between the two roles, and an unusual arrangement in European oncology, especially for someone in mid-career. But such portfolio positions are likely to become more prevalent in cancer centres precisely because of the need to have specialists and not administrators in the frontline of networking and benchmarking work, to improve research collaboration and care outcomes.

Saghatchian was born in Iran before the Islamic revolution, and although her parents were not involved in politics they chose to leave for France with their two daughters when it became apparent that opportunities for girls under the new regime after 1979 would be limited. “I chose to study medicine partly because I had important family figures who had been in medicine – my grandmother was one of the first Iranian women physicians – and also because I wanted a profession I could do anywhere in the world.”

Her sights were set firmly on entering a specialty with a strong and growing research component, and she quickly rejected fields such as cardiology in favour first of immunology, and then oncology, but she candidly admits that, even relatively recently, she found medical oncology lacked much research promise, comprising as it does mainly chemotherapy. “If I’m honest, really the most gains have been in surgery and radiotherapy in my field of breast cancer – it is only lately that we have personalised molecular therapies and I think medical oncology’s time is very much to come in breast cancer. In our tumour board meetings at IGR we have a lot of discussion about surgery and radiation choices, but it’s always the same adjuvant therapies – there has not been much change, apart from Herceptin.”

A case in point for the future is her own research for a PhD. “I have been looking at breast cancer patients who relapse late – half of the 30% who relapse do so after five years, but all trial work is on short-term rates, up to five years – no one is looking at how to prevent late relapses, as we don’t understand them and can’t select those patients and treat them accordingly. I’ve been doing microarray profiles to see if we can find predictive markers for relapse and targets for treatment. It’s almost finished – we have identified a set of 214 genes that predict late recurrences and a gene that is overexpressed.”

A case in point for the future is her own research for a PhD. “I have been looking at breast cancer patients who relapse late – half of the 30% who relapse do so after five years, but all trial work is on short-term rates, up to five years – no one is looking at how to prevent late relapses, as we don’t understand them and can’t select those patients and treat them accordingly. I’ve been doing microarray profiles to see if we can find predictive markers for relapse and targets for treatment. It’s almost finished – we have identified a set of 214 genes that predict late recurrences and a gene that is overexpressed.”

Saghatchian’s PhD supervisor is Laura van ’t Veer, the pioneer in gene expression profiling, and the work is exactly the kind of translational research that demands more cooperation among European centres, she says. It is why advocates of TRANSBIG’s MINDACT adjuvant therapy profiling trial are so enthusiastic – not about the primary question so much, but the ‘goldmine’ of frozen tissue samples from 6000 patients and the collection of expression data from 44,000 arrays. “It’s why we participate in MINDACT at IGR, but it has been the other main controversial area for me, along with the accreditation tool. There is almost a religious divide between those who believe in the Mammaprint gene profile and those who don’t, but for me it’s not about belief but about science. Every day we use markers that have not met full approval in an evidence base – but that shouldn’t prevent us from going on with the research.”

Saghatchian spent five years as a medical oncology fellow at IGR, before moving to an academic general hospital in Paris, the Georges Pompidou European Hospital, where she looked after lung cancer patients, among other roles, for two years. “I found that oncology away from cancer centres can be a really different job. There can be a fear of cancer patients and a misunderstanding of what’s possible in the emergency unit, for example. In day-to-day care we didn’t have palliative care teams or pain specialists, and no molecular profiling – that had to be sent elsewhere – and it is impossible to do research when you don’t have enough patients. My own expertise suffered because I didn’t see rare cases, and if I did I might not have known how to treat them well.”

It is highly unlikely that such hospitals could meet OECI criteria, but Saghatchian says that publicity for centres that do become accredited may help patients and primary care doctors make more informed referral decisions. “There is little information for patients about where the best care and specialists are. This isn’t just true for oncology of course but for all specialisms – you often go to where you are told to go or where your friends went.” In hospitals that have a cancer department there is a tendency also for surgeons to refer patients there rather than to external cancer centres, which is part of the long-standing discussion about the primacy of organ-based practitioners versus multidisciplinary oncology.

“There is little information for patients about where the best care and specialists are”

Many large general hospitals do have comprehensive cancer centres, and Saghatchian acknowledges the extra resources that can be brought to bear from other specialists. She is keen to stress that any hospital with a cancer centre is free to seek accreditation, but concedes that some smaller ones will be content with national systems, and are not seeking international recognition. Unicancer, the French programme, and other national initiatives are beginning to apply rigorous audit – the NHS in England, for example, has started local audit of colorectal, lung, oesophago-gastric and head and neck cancers, in some cases at the level of individual units.

“But it is also the case that national systems such as ours in France are applying only basic minimum standards for oncology in most smaller hospitals, such as the number of breast operations that need to be done. It’s why cancer plans tend to fail in my view – politicians often won’t make the tough decisions to close oncology departments that do not meet higher standards.”

“Politicians often won’t make the tough decisions to close oncology units that do not meet higher standards”

Saghatchian returned to IGR in 2003, but asked director Thomas Tursz for a position that would not be a full time clinical post. “It was partly because oncology was a bit dull and also tough with so many dying patients – I didn’t want to suffer from burn out – but it was also about my personal history as a foreigner. Even at medical school I had run a small society for foreign students and had the feeling that international exchange work was a great way to keep yourself fresh and learn more. Thomas wanted someone to develop international affairs and he created the job for me.”

As she points out, it is perhaps surprising that more cancer centres do not have similar roles. “None of the other centres in France has someone like me I believe, but it is very important for IGR to have a unit to attract funds for research programmes and be a voice for the centre.”

Her half-time post relates directly to the aims of the OECI accreditation project, which is why she has been so keen to champion it in Europe, although there is an element of competition. “At IGR we were finding it hard to get funding for academic research, but now we are much more organised about the way we respond to ‘calls’ for European framework projects, for example. In the 7th Framework Programme we are involved in more than 20 calls that are now a major source of income. Before it was just an ad hoc effort by a few staff who knew what to do.”

That may be competing with other centres to some extent, but Saghatchian adds that new partnerships are forged within programmes such as TRANSBIG and CHEMORES. “In the CHEMORES lung cancer and melanoma FP6 project, for example, we didn’t know some of the other partners well at all. Now it’s finished, a lung project has emerged that’s independent and wouldn’t have happened without the original programme. Basic scientists tend to know each other around the world, but in translational research, clinicians often don’t know who best to work with and who has the best infrastructure.”

Saghatchian considers that IGR now pretty much meets the OECI criteria for a true comprehensive cancer centre, but it’s taken a lot of work, driven especially by previous director Tursz. “We have national quality assessment and benchmarking of French centres through Unicancer, which checks aspects such as multidisciplinary care. Five years ago, only 70% of breast cancer patients were discussed by multidisciplinary teams – now it’s 100%. Thomas also changed department heads who weren’t doing well, made IGR attractive for young people to do PhDs and to work abroad, and not least we had a major interior refurbishment six years ago – although the outside is still rather grim.” Lex Eggermont, the current director, was a brave appointment, she adds, as he is Dutch, but has made an impact with excellent financial management and has further boosted IGR’s international standing.

The experience so far with OECI accreditation, says Saghatchian, is that standards of care – such as the percentage of patients seen by multidisciplinary teams – are relatively straightforward to compare among centres. “It’s harder to look at research and education programmes, and also the integration of research with care. The cultural and organisational differences between countries are also big challenges of course, and we have no plans to work in any language other than English.”

Establishing definitions and questions for collecting data that avoid misunderstandings and compare like with like has taken a lot of effort, even with seemingly simple factors such as the number of patients treated, and the resources and infrastructure in place.

“And one of the main issues that the project has revealed is just how difficult it is for centres to collect data about themselves – we’ve realised that senior management often do not have a clear picture of what exactly is going on in their organisations. One very tough question is, ‘What is your research budget?’ But the data are often not centralised and you do wonder how they manage without crucial information like this. And the bigger the institution, the more difficult it can get.”

“We’ve realised that senior management often do not have clear picture of what exactly is going on”

A case in point is King’s Health Partners in London, which is currently in progress with its OECI application. “It’s definitely harder for centres such as King’s to collect data because it has multiple sites, where people may not be measuring the same things, or in the same way.” Meanwhile an example she cites where reviewers found research and clinical care integration is not as strong as it could be is at Helsinki University Hospital. “They did not find a specific organisation for translational cancer research. But we are finding that centres welcome the review process because it does help them to highlight areas that need development and gives them evidence to ask for more resources.”

For the time being, a country that will be notable for its absence in the OECI accreditation programme is Germany, except for DKFZ in Heidelberg, which is a EurocanPlatform member. Saghatchian explains that is mainly because of Germany’s history of treating cancer by organ specialists, with all the controversy that has created. “The German Cancer Society has its own certification strategy and organisation, OnkoZert, for progressively addressing the issues rather than tackling them head on. The German problem is specific to the country and we won’t do much there in next few years except for a pilot.”

For the time being, a country that will be notable for its absence in the OECI accreditation programme is Germany, except for DKFZ in Heidelberg, which is a EurocanPlatform member. Saghatchian explains that is mainly because of Germany’s history of treating cancer by organ specialists, with all the controversy that has created. “The German Cancer Society has its own certification strategy and organisation, OnkoZert, for progressively addressing the issues rather than tackling them head on. The German problem is specific to the country and we won’t do much there in next few years except for a pilot.”

In fact, following a move to establish second opinion services for testicular cancer, an increasing number of prostate cancer units have been certified in Germany – as many as 68 by last year. This experience is feeding into work by ESO and OECI on establishing a prostate unit standard . “There is certainly a huge need. Even at IGR we don’t have a formal prostate unit and we would welcome guidelines and care pathways for prostate cancer.”

In the current revision of the accreditation, Saghatchian says some basic standards will be removed because they are common to all. ‘We are fine-tuning the quantitative data to develop indicators that show differences. For example, one of the ambitious indicators we want is to compare survivorship between centres – the outcome data. That means collecting the same data on patients at the same time for their disease, including follow-up. At present we can only look at country registry data across Europe – but that doesn’t show where a patient was treated.”

Saghatchian feels the OECI has taken a lead in driving forward the benchmarks for improving outcomes in Europe, and she has certainly brought a great deal of passion to her European work. She expresses frustration that other organisations do not seem to have the same focus. She would like to see the EORTC, which organises international cancer trials, continue its modernisation towards translational research; ECCO, she says, needs to articulate its vision better; and advocacy groups should be pushing much harder for breaking down regulatory barriers, such as in tumour collection. “We are trying to launch a neo-adjuvant trial where we want to collect samples before and after giving Herceptin – but as there is no immediate benefit we can’t do it. It’s one reason why progress in personalised medicine is slow.” She would also like to see the research community become much more imaginative in using the talents in other fields, such as mathematics.

Another factor slowing progress, she adds, is a chronic under-use of IT – “I’m amazed we don’t do more with tools such as iPhones and email. Sometimes I get the feeling people are happy to slow down the pace of work because of fear of overload.” That applies at IGR as elsewhere – and the use of modern IT is one of the OECI standards – but otherwise her centre is now doing better than ever, she says, with its recent refurbishment and improved efficiency leading to more funding. “The French health system though is slipping in quality and access and we are facing even more pressure from the pharmaceutical industry. We’ve had some drug scandals, such as with a diabetes pill, which is causing mistrust towards doctors.”

Some less pressurised aspects of her work at IGR included helping to produce a book of paintings of breast cancer patients, and a study on the impact of using beauty treatments on self-image and depression, carried out with l’Oréal. And she has not forgotten her roots, setting up a link between IGR and MAHAK, an organisation in Iran that helps children in the country receive cancer treatment.

Above all, the theme that best sums up her approach is networking and movement. “I love the European work – you learn so much when you move around and people should definitely aim to work in other countries.”

Perhaps the OECI accreditation process will introduce a measure of foreign personnel and movers in future.