The impact chemotherapy can have on the ability to think clearly is well recognised. Less is known, however, about the cognitive effect of endocrine therapies, which in the adjuvant breast cancer setting are being prescribed for up to 10 years. Wilbert Zwart, Sanne Schagen and colleagues from The Netherlands Cancer Institute, review the evidence.

This is an abridged version of W Zwart, H Terra, S Linn, S Schagen. Cognitive effects of endocrine therapy for breast cancer: keep calm and carry on? Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology (2015) 12:597-606. It was abridged by Janet Fricker and is published with permission.

© 2015 Nature Publishing Group. doi:10.1038/nrclinonc.2015.124

Three quarters of breast cancer patients are eligible to receive endocrine treatments – tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitors (letrozole, exemestane and anastrozole). It is therefore very important to understand their potential adverse neurocognitive effects, particularly now that the guidelines are recommending increasing the duration of therapy from five to 10 years.

Increased awareness of the importance of oestrogen in stimulating neuroplasticity and improving cognitive performance has focused research on evaluating the cognitive effects of breast cancer endocrine treatments.

A recent review that summarises more than a decade of research indicates that cognitive decline affects 20–60% of patients after chemotherapy (CA Cancer J.Clin 2015, 65:123–138). Patients show changes from pre to post chemotherapy with regard to learning and memory, speed of information processing, and executive functioning. However, most studies have not been designed to address the effects of endocrine therapy, either alone or in combination with chemotherapy.

Studies that explore the influence of endocrine therapy on cognition are often underpowered, with flawed designs, that ignore relevant factors such as the use of hormone replacement therapy (HRT) and age at menopause.

Any effects of endocrine therapy in breast cancer patients, independent of chemotherapy, need to be explored. Furthermore, since guidelines permit the choice between different endocrine regimens, knowing how each option could potentially impact on cognition might influence the decisions made in individual cases.

Oestrogen effects on brain physiology

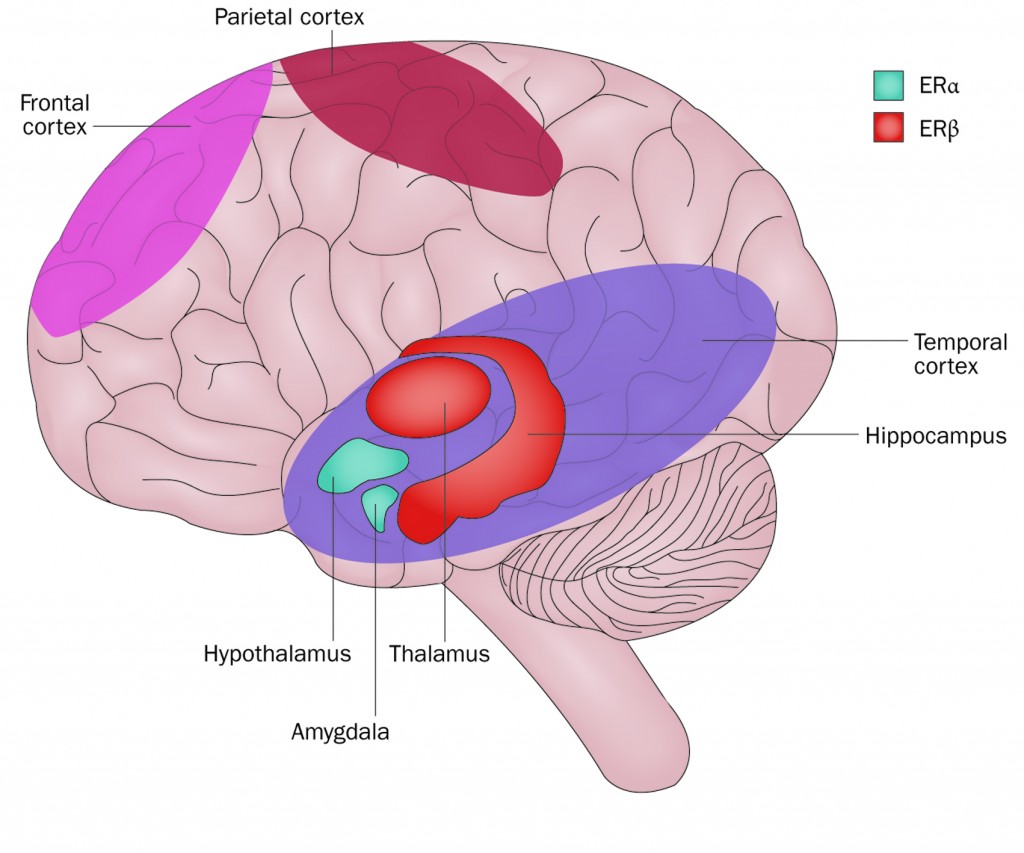

Both oestrogen receptors, ERα and ERβ, are expressed throughout the brain, although ratios vary. In general, ERβ is expressed at high levels in the hippocampus and temporal cortex; while ERα is expressed at higher levels in the amygdala and hypothalamus.

Multiple studies have indicated that aromatase inhibitors (AIs) and tamoxifen can cross the blood–brain barrier and enter the brain. All AIs inhibit both ERα and ERβ activity. By contrast, tamoxifen has a mild stimulatory effect on ERα function and completely blocks ERβ activity (Cancer Res 2001, 61:2537–41). It is the ratio of ERα to ERβ that may influence the effect of tamoxifen on neuronal function.

Preclinical data on cognition

Animal models of oestrogen deprivation (ovariectomy) show impairment of cognitive function: rodents and monkeys illustrate decreased cognitive performance in spatial memory and working and reference memory.

In these preclinical studies, the effects of tamoxifen and AIs on cognition have proved less conclusive. Mouse studies report adverse effects for tamoxifen, including impairment of memory consolidation and retrieval. In rats, AIs improved spatial learning and memory, but impaired hippocampus plasticity. Furthermore, in ovariectomised rodents, tamoxifen possessed oestrogen-like agonistic effects on the serotonergic system, neuroprotective functions in the dopamine and acetylcholine system, and increased hippocampus plasticity.

ER knockout studies suggest adverse effects of endocrine therapy may be largely mediated by ERβ: mice lacking ERα showed no difference in neuronal morphology, while those lacking ERβ had cognitive deficits, such as reduced context–cue memory (Mol Endocrinol 2007, 21:1–13).

The neuroprotective functions of oestrogens and tamoxifen may be explained, in part, by the prevention of neuronal cell death, controlled partially by ERs (Endocrinology 2003, 144:306–312).

Hormones and cognition in healthy women

Studies have explored hormonal influence on cognitive function at different stages in the reproductive lives of healthy women.

During the menstrual cycle, higher levels of oestrogen can have a subtle impact on cognition, with beneficial effects for functions where women excel (such as verbal fluency) and unfavourable effects for cognitive functions where men generally excel (such as spatial function). Studies in post-menopausal women suggest those with higher oestrogen have better verbal memory and retrieval efficiency; while those with lower oestrogen have better visual memory.

Three large cohort studies suggest premature menopause affects verbal fluency and visual memory in later life and may increase dementia risks. One study, for example (Neurology 2007, 69:1074–83), showed women undergoing oophorectomy before the onset of menopause have increased risks of cognitive impairment and dementia (HR=1.46 compared to reference populations).

In contrast to several observational studies showing reduced risk of Alzheimer’s disease in HRT users close to their final menstrual period, the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study (WHIMS) reported HRT (oestrogen plus progestin) significantly increased dementia in women aged 65 years or older (JAMA 2003, 289:2651–62). For women receiving only oestrogen, no significant effects were found.

The WHIMS study supports the ‘critical window’ hypothesis, where the benefits of HRT on cognition are limited to early initiation of treatment. While a ‘critical window’ has also been observed in animal studies, mechanisms underlying such effects remain poorly understood.

Against this background, there is a need to understand how breast cancer endocrine therapies may affect brain health and to investigate clinically relevant cognitive risks.

Evaluation of such adverse effects remains challenging due to other factors affecting cognition, including chemotherapeutic agents. Cognitive testing is now being incorporated into the design of several clinical trials, allowing opportunities to further explore such issues.

Neuropsychological examinations

Studies of other patient populations with cognitive problems (such as traumatic brain injury) indicate that ‘self-reported cognitive function’ provides an insufficient proxy, since it is weakly associated with tested cognitive function, and strongly associated with individual mood.

Together with neuropsychological assessment, such information is, however, critical to the differential diagnosis of a cognitive disorder and introduction of intervention strategies.

CASE STUDY

Cognitive impairment following endocrine treatment

A 55-year-old postmenopausal elementary school teacher with breast cancer, treated with breast conserving surgery, radiotherapy and tamoxifen, became aware of cognitive difficulties including problems with name retrieval, organisation skills, distractibility, and need for increased mental effort to memorise instructions.

A neuropsychological examination revealed she had diminished ability to learn new information (corresponding to the 1st percentile), lower than expected recall of previous learned information (corresponding to the 7th percentile), and underperformance of lexical and semantic fluency (corresponding to the 16th and 14th percentiles, respectively).

Interventions were offered including learning compensatory strategies to reduce interference of cognitive difficulties at work, regain resilience and diminish stress.

Oestrogens and cognition: clinical data

Cognitive studies conducted as part of randomised clinical trials in postmenopausal women suggest a potential adverse influence on cognition of tamoxifen but not AIs, though these results are inconclusive.

In the Arimidex Tamoxifen Alone or in Combination (ATAC) study, involving the AI anastrozole alone, tamoxifen alone, and combination of tamoxifen plus anastrozole, patients with cancer scored significantly worse on verbal memory and processing speed compared to controls without cancer (Psycho-Oncology 2004, 13:61–66). No distinctions were made between different endocrine therapies.

In the Tamoxifen Exemestane Adjuvant Multinational (TEAM) study, neuropsychological assessment at one year showed tamoxifen users performed significantly worse than controls without cancer, with regard to verbal memory and executive functioning, and worse than exemestane users on information processing speed. Exemestane users did not perform significantly worse on any domain compared to controls. (JCO 2010, 28:1294–1300).

The BIG 1-98 trial found that patients treated predominantly with letrozole achieved better cognitive scores than those treated predominantly with tamoxifen (Breast Cancer Res Treat 2011, 126:221–226).

Finally, in the International Breast Cancer Intervention (IBIS) II prevention study, where postmenopausal women were randomised to anastrozole or placebo, cognitive function did not differ between treatment groups (Lancet Oncol 2008, 9:953–961).

These studies suggest tamoxifen but not AIs may affect cognition, but results are less clear regarding the effects of endocrine therapy per se on cognition, as some studies (such as BIG 1986 and ATAC) report worse performance for all patients on endocrine therapy (either tamoxifen or AIs) compared with controls. It is noteworthy that relevant information on background hormone use, previous HRT, and age since menopause has not been systematically taken into account.

Observational studies

The four observational studies evaluating cognitive effects of endocrine therapy in patients who were chemotherapy naïve found post-menopausal women using tamoxifen performed worse on verbal abilities than non-cancer controls. One study including 14 postmenopausal women taking anastrozole found that women taking anastrozole, in particular, had greater cognitive decline in processing speed and verbal memory, but since this group was particularly small, results should be interpreted with caution (Psycho-Oncology 2009, 18:811–821).

Five additional studies have evaluated the influence of endocrine therapy on cognition, but also included patients who received prior chemotherapy. Two studies did not find adverse effects for endocrine therapy. The third study showed a negative effect of anastrozole on visual and verbal learning as well as memory (Menopause 2007, 14:995–998). The fourth study showed patients taking endocrine therapy reported increased language and communication complaints compared to cancer patients not undergoing such therapy, and furthermore this was associated with diminished psychomotor function (JCO 2014, 32:3559–67). Finally, for a subset of patients, the fifth study showed regionally specific changes in metabolic brain function on PET scans following AIs (Clin Breast Cancer 2014, 14:132–140).

Conclusions

With multiple clinical trials indicating prolonged adjuvant endocrine therapy improves outcomes for breast cancer patients, the value of these treatments in managing breast cancer remains beyond doubt. Nevertheless, studies suggest endocrine therapy can potentially have adverse effects on cognitive function.

Attention needs to be paid to whether the observed changes in cognition associated with cancer therapies adversely impact aspects of everyday functioning that matter to patients, such as employment. Elucidating the clinical significance of side effects further would help to identify the therapies that have least impact on physical and mental morbidity.

A core set of cognitive tests measuring memory, executive function and processing speed have been developed by the Response Assessment in Neuro-Oncology (RANO) working groups and the International Cognition and Cancer Task Force (ICCTF). The incorporation of these tests, already widely adopted by the EORTC, RTOG and other consortia, into clinical trials for endocrine therapy could help elucidate potential adverse cognitive effects.

Future development and implementation of predictive biomarkers might enable identification of patients who have excellent prognosis and are unlikely to derive sufficient benefit from adjuvant endocrine treatment to justify their use.

IN SUMMARY

Take home message

Studies involving neuropsychological assessments before treatment are needed to determine the potential cognitive effects of endocrine therapy and identify patients who might be at risk of treatment-associated cognitive decline. As current guidelines permit choice between different endocrine regimens in treating breast cancer, identifying potential cognitive effects associated with different options might influence individual choice of therapy.

Clinical implications

The continuing search for biomarkers that predict selective benefit from adjuvant endocrine therapies is likely to identify breast cancer patients who have an excellent prognosis and would be unlikely to derive sufficient benefit to justify their prescription. For those who do benefit from endocrine therapy, more research is needed on the potential impact on cognition. At this stage no clinical practice implications are justified, as our knowledge on the actual incidence and severity of cognitive changes associated with endocrine therapies is too limited to be included in clinical guidelines.

Future studies

Standardised testing of cognitive function should be better incorporated into clinical trial design for endocrine treatments, with outcomes related to effects on quality of life. Variables on hormonal background (including HRT, age, age at menopause, and chemotherapy) should be well documented.