Csaba Dégi is all set to study how patients in Romania transition back into primary care after their treatment is over, as part of current international efforts to focus on the needs of survivors. That’s something to be proud of, he tells Janet Fricker, given that as recently as ten years ago only a minority of patients in his country were even told they had cancer.

Emotional and social distress require monitoring and attention just as much as the traditional ‘vital signs’ of temperature, pulse, blood pressure, respiration and pain. This sentiment – along with the emergence of the field of psycho-oncology – has its origins in the West. Csaba Dégi, a pioneer of psycho-oncology screening in Romania, has spent his career trying to put the philosophy into practice in his home country.

Dégi , who works as an associate professor in the Faculty of Sociology and Social Work at Babes-Bolyai University in Cluj-Napoca, argues that the right intervention at the right time can be the thing that enables people to continue living their lives in the face of a cancer diagnosis. “Cancer patients face a whole continuum of distress that ranges from low level distress that people can manage themselves to elevated distress, including clinically relevant depression and anxiety, that stops them functioning,” he says. “Without support they become marginalised and experience a very lean survivorship.”

In Romania, psychosocial provision for cancer patients is still regarded as something of a luxury rather than as an essential component of cancer care. Although more than 78,000 patients are newly diagnosed with cancer each year, only around 5% to 8% of them receive any professional psychological or social care. With studies estimating that between one and two out of every three cancer patients experience some level of psychosocial distress, there is clearly a huge unmet need.

Dégi attributes the shortage of professionals primarily to shortcomings in the National Cancer Control Plan, which makes no mention of psychosocial oncology care. Romania has no recognised accreditation programme for psycho-oncology training, he adds, with only around 20 psycho-logists and 10 social workers serving the country’s four main cancer centres. “There’s no official job title of ‘psycho-oncologist’, with the result that it’s completely pot luck whether cancer patients have any access to the psychosocial services they so desperately need,” says Dégi, who is all too aware that in poorly resourced countries funding of cancer treatment needs to take priority.

The situation in Romania is far from unique, however. Throughout the rest of Europe, Dégi adds, provision can be extremely patchy, with few countries fully integrating psychosocial oncology into their medical system. A survey by the European Partnership for Action Against Cancer (EPAAC), involving 27 representatives of European countries, showed that only eight (fewer than one in three) reported having nationally recommended clinical guidelines for psychosocial oncology care, only 10 (fewer than two in five) had specific budgets for such a service, and only six (just over one in five) had an official certification programme for educating psychosocial oncology professionals (Psychooncol 2017, 26:523 – 30). Indeed, only the UK and Germany can be considered to have fully integrated psycho-oncology into mainstream services.

Smart screening

After battling successive Romanian ministers of health to include psychosocial oncology in the national cancer programme, Dégi is now focusing his energies on promoting screening. It’s urgently needed, he explains, because cancer care professionals all too often confuse clinical depression (feeling hopeless, helpless, worthless or suicidal) or anxiety disorders (phobic avoidance, agitation and constant worry) with normal sadness. Dégi has decided to take a pragmatic approach by developing an innovative smart phone app – APSCO (Assessment of Psycho-Social and Communication needs in Oncology patients) – that patients can use at home to screen themselves for distress.

The app, based on the work of Alex J. Mitchell, from the University of Leicester, UK, consists of a visual system of five thermometers covering distress, anxiety, depression, anger, and the need of help, which cancer patients can use to rate how they are feeling on a scale of 0 to 10, similar to the way pain is reported. After calibrating the sensitivity and specificity of the app for use in the Romanian population, Dégi has settled on a cut-off value of any score above 4 as an indication patients require further evaluation.

“The app is needed because it’s really hard for patients to judge whether they’re experiencing normal suffering or require extra help,” says Dégi. “We want patients to use it at least once a week, as emotional distress isn’t constant and can be triggered by different stages of the illness trajectory.”

Once distress has been flagged up, patients need to be further evaluated, he says, and they can then be offered a range of treatments, depending on levels of distress and co-morbidities, including supportive expressive therapy, solution-focused therapy, mindfulness, narrative, cognitive behaviours, and psycho-pharmacology. The app itself also includes a database of psycho-oncology resources in Romania and advice on meditation and guided relaxation.

A question of justice

Dégi did not start out with the career of social work in mind, but instead attended theological high school with a view to training as a protestant priest. “I come from a tough background with lots of hardships. My parents were ambitious for us and realised that the main opportunity for education was through the seminary,” he says. Feeling disappointed with the church as an institution, Dégi instead chose to study for a Bachelor’s degree in social work at Babes-Bolyai University, in Cluj-Napoca.

“For me faith is about finding meaning in life, which provides peace of mind. I didn’t feel that this needed to take place in a theological framework and found social work connected me to values of being human and provided an outlet for my desire to fight social injustice,” he says.

While still at University, a defining moment in Dégi’s life was the death of his father János, at only 49 years old, from lung cancer. “The cancer was undoubtedly caused by exposure to industrial chemicals – virtually all of my father’s work colleagues from the factory died of cancer before the age of 54. The experience has meant that I understand first hand the isolation of cancer patients and the far-reaching effects that reverberate throughout their families,” he says.

“I understand first hand the isolation of cancer patients and the effects that reverberate throughout their families”

Dégi started off working in child and family health, specialising in drug addiction, for his PhD in medical psychology at Semmelweis University, in Hungary. But he focused his attention on the emotional experiences of Romanian patients hospitalised with cancer. “I concentrated on the Romanian situation, because Hungary has a 40-year history of psycho-oncology,” he explains.

Getting access to cancer patients, he recalls, was “little short of a miracle”.

“Over the weekends cancer patients were kept in complete lockdown with no opportunities for visitors,” Dégi remembers. He had to rely on nurses, who had become convinced of the value of his work, to smuggle him in. “To me it was completely outrageous that dying patients were treated as nobodies, and locked out of society,” says Dégi, adding that the only support they were given was by priests, offering bible readings and prayer.

“I recognised that these people were really isolated, and wanted dialogue about their emotions, distress and fears. They wanted to talk through decisions they needed to take, like what to tell their children,” he says. An important early realisation was that ‘nice words’ were all very well, but changing systems requires good-quality evidence. “Although at heart I’m a patient advocate, I quickly realised that I needed to develop the mind-set of a researcher,” he says.

Let the patient know

The issue around telling patients the truth about their diagnosis became an important aspect of his research after he became aware of how physicians and family members collaborated in a ‘conspiracy of silence’. “Revealing the diagnosis to cancer patients was felt to be too cruel, because you were taking away their hope. The prevailing view was that people coped better not knowing,” he says.

Dégi’s research showed that, in 2007 (before Romania joined the European Union), fewer than two in ten cancer patients were informed about their diagnosis (Supportive Care Cancer 2009, 17:1101-07), whereas by 2014, when disclosure had become a legal right, this had risen to more than nine in ten. Dégi and colleagues conducted a study to assess the difference disclosure made to patients’ mental health. They found that patients who were not informed about their cancer diagnosis were significantly more depressed, and had lower levels of problem-focused coping, compared to patients who were informed (Psycho-oncology 2016, 25:1418–23).

Disclosure, Dégi maintains, brings many benefits, including allowing the possibility for patients to have free and open communications with friends and family members about cancer. “It’s impossible for people to adjust to something they don’t understand,” he says. But despite the dramatic fall in non-disclosure levels in the second study, he found patients did not experience a corresponding improvement in quality of life. “Even though we were starting to communicate more openly about cancer, the problem was that there were no services in place to help patients,” he says.

For Dégi the findings triggered painful memories about his father’s death. “We had taken the decision not to tell Dad about his diagnosis. But when he eventually figured out for himself that he had cancer, he felt terribly betrayed that we hadn’t shared the information with him. Sadly we never succeeded in restoring the trust between family members.”

In 2016, Dégi published his book ‘Psychosocial oncology needs: an absent voice in Romania’, with the intention of providing a snap-shot of psycho-oncology care that could be used as evidence of the need to provide psychosocial oncology services in Romania. The book, which involved questionnaires and structured in-depth interviews, was unusual in being published from the outset in Romanian, Hungarian, and English. “I made the conscious decision to publish in three different languages to get the messages out to as many people as possible,” he says.

“When he eventually figured out for himself that he had cancer, he felt terribly betrayed that we hadn’t shared the information with him”

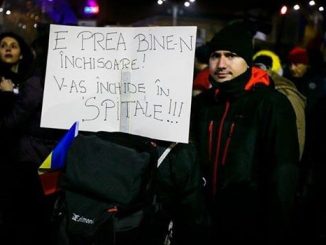

In his quest to bring about change Dégi, who describes himself as “naturally shy and introverted”, has needed to assert himself and become politically active. In 2016, he was a member of the steering group formed to develop the National Cancer Control Plan for 2016–2020, with special responsibility for psychosocial oncology care. “It’s been incredibly frustrating, because the new programme, which included a psychosocial action plan, was launched at a big event in Bucharest, but the document was never published and is still languishing on a shelf at the Ministry of Health,” he says.

The problem, he explains, is that Romania has had four different ministers of health in the last few years. “Every time I meet a new minister, I need to start from scratch explaining the importance of psychosocial oncology,” Dégi says. But he’s encouraged by the fact that, when palliative care was first introduced in Romania in the 1990s, there was little support from the national medical system, and yet by 2015 it had become an integral part of cancer care, with 115 specialists now employed in palliative care services.

Building capacity

With this optimistic outlook Dégi is mindful of the need to train the next generation of psychosocial oncologists and, in his current post in the faculty of Sociology and Social Work at Babes-Bolyai University, he runs an undergraduate course in oncology social work (20 students) a Masters in psycho-oncology (80 students) and a PhD programme in heath sociology (three students).

But as he says, “there’s still a generation of oncologists in Romania who have had no training in communication skills.” To address this gap, he has been working with the International Psycho-Oncology Society (IPOS) to establish specialist training programmes in Romania. In 2013/14 he organised a series of training sessions for doctors and psychologists from the public health system, to improve their skills in conducting difficult communications – including breaking bad news and talking about intimacy and sexual life – and so far has trained 60 doctors and 40 psycho-oncologists. “We operate a cascading system, where the professionals we train offer local training to colleagues.”

Dégi was also influential in forming the Romanian Association for Services and Communication in Oncology, an organisation supporting cancer patients and their families that provides a data base of psychosocial services. “We connect the dots, helping patients navigate services, and push the psychosocial oncology agenda forward.”

An international player

Dégi talks about what an inspiration it was for him to meet many of the early pioneers of psychosocial oncology, including Lea Baider, from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Maggie Watson, from the Royal Marsden Hospital in London, who edits the Psycho-Oncology Journal, and the late Jimmie Holland, from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, in New York, who is widely recognised as the founder of psycho-oncology. “Jimmie told me that, in the 1960s, the psychosocial oncology situation in America was like Romania in 2007, before we joined the EU. People just didn’t talk about ‘the big C’. And just like me, but decades earlier, Jimmie did the research that built the evidence to show that there was a need for psychosocial oncology,” says Dégi.

Today Dégi increasingly contributes at an international level. He is an IPOS director, representing eastern European regions, he was part of the panel that drew up the psycho-oncology section of the ‘Essential Requirements for Quality Cancer Care’ published by ECCO (the European Cancer Organisation). He is especially proud of having been recruited by Leslie Fallowfield, professor of psycho-oncology at Brighton and Sussex Medical School, in the UK, who has been hugely influential in the field, to facilitate a workshop training eastern European doctors to use more focused and open questions, show increased levels of empathy, and respond more appropriately to patient cues. “For me a big benefit of the course was that it gave me instant access to the Romanian oncologists that I’d been trying to reach to talk to about the importance of psychosocial oncology,” he says.

Next, Dégi plans to study the transition of cancer patients who have finished treatment, from cancer centres back into primary care. As with his other studies, the first part of the process will be to gather information, identify needs and then plan for change. “All my career I’ve been playing catch-up, doing studies 20 to 30 years later than my colleagues from the West. But this time I’m really excited to be taking part in an international research network that allows me to be in step with my colleagues from developed countries.”