It was stumbling across a poster for a meeting about cancer in the developing world that turned journalist Joanne Silberner from a sceptic into a believer, and prompted her to do her bit to change fatalistic attitudes about tackling the disease in poorer countries.

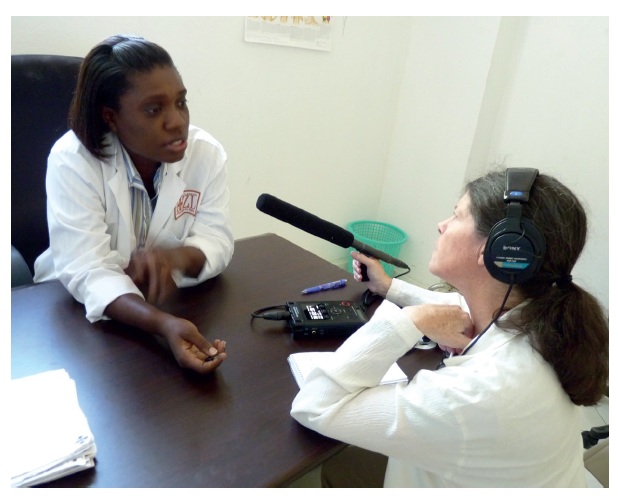

Outside a cancer outpatient centre in Kampala, Uganda, the sound of women sweeping paths with brushes made of twigs; inside the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, the hum of a centrifuge. Journalist Joanne Silberner hears the soundscape as a metaphor for the technological gap between a state of the art centre and the basic service in a developing country, available only to the most fortunate of patients.

But the story that Silberner tells is not only about contrasts. She has highlighted collaboration and a sense of optimism as the world starts to address cancer in low- and middle-income countries, where it causes more deaths than AIDS, malaria and TB combined, but receives a fraction of their funding.

For her series entitled “Cancer’s New Battleground – the Developing World”, on Public Radio International, and for supporting pieces in the Seattle Times and on KUOWradio, Silberner was named one of the two joint winners of the European School of Oncology’s Best Cancer Reporter Award for 2013. Silberner receives € 5.000 for the award that recognises the focus she brought to the growing crisis of cancer in developing countries, the neglect that surrounds this issue and the need for urgent action.

However, this prize-winning series nearly did not happen. Silberner, who reported for National Public Radio in Washington DC for 18 years, now freelances in Seattle and sees her mission as exploring neglected health topics. She has covered tropical diseases and mental health, but cancer almost got away.

“I saw a poster for a meeting at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Institute about cancer in the developing world. Seattle is very globally orientated; people think they can save the world. But when I saw this poster I thought this is crazy – nobody lives long enough in the developing world to get cancer, and even if they did, there is no way you can get the technology to treat them. So I went to this symposium thinking they will have nothing to say.

“I was absolutely stunned to hear how many cases of cancer there are, and the lack of treatment, but also the possibility and ease of treatment. I heard that the success rate is not zero – there is a real difference you can make even in a developing country.”

She looked to see who was reporting this and found some pieces in the New York Times which seemed only to emphasise the awfulness, “five anecdotes in a row of people dying in front of the reporter’s eyes.” She knew she wanted to do something different, “to show that at least there is something that can be done if people get interested.”

With financial support from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting, Silberner visited Uganda. She met Jackson Orem, who had studied in the United States but returned to pioneer cancer treatment and, for a while, was the only practising oncologist in this country of more than 30 million people. Even today, 20,000 of the 22,000 patients attending the Uganda Cancer Institute each year die within a year. Orem and his five new oncologist colleagues have been able to offer mainly pain relief and care.

She wanted to do something different to show that something can be done if people get interested

An increasing priority

That is changing through a link with the Hutchinson Center, which includes exchange visits, research and training, and with a higher priority from the Ugandan government, which commissioned a 200-bed specialist hospital. Although some Ugandan languages still have no word for cancer, awareness is growing and so are treatment options. “The truth of the matter is that cancer is a disease of the African person just like any other person elsewhere in the world,” Orem told her. “People are much more receptive to our messages than before.”

Silberner’s visit provided the basis for the first of her PRI broadcasts in December 2012, entitled “Cancer’s Lonely Soldier”. She followed this up with a piece focused on viral cancers, including Burkitt’s lymphoma – the most common childhood cancer in sub-Saharan Africa – and Kaposi’s sarcoma, which is often found in people with HIV infection. She also highlighted the difficulty in accessing morphine, although the drug is a cheap and effective way of controlling pain. Silberner cited the chilling World Health Organization statistic that more than five million people with cancer die in pain each year.

In Haiti, Silberner accompanied oncologist Ruth Damuse from the local group Zanmi Lasante on International Women’s Day as she spoke to women about the need to report symptoms in a country where 50% of women diagnosed with breast cancer present too late for their lives to be saved. We hear medical staff in Haiti consult colleagues at the Dana Farber Cancer Institute in Boston on a speaker phone, receiving advice that is tailored to available technology and chemotherapy. This link was established by the US charity Partners in Health, and the head of their cancer programme, Sara Stulac, insists that treatment can save lives as well as reduce suffering. She points out that AIDS drugs were once considered too costly and difficult to deliver in developing countries, yet millions of people with HIV in Africa and Haiti are now routinely treated.

In India, Silberner saw the use of acetic acid (vinegar) to test women for the early signs of cervical cancer, and heard how teams from the Tata Memorial Hospital in Mumbai and Walawalkar Hospital in Maharashtra have worked patiently with women and men in rural communities to overcome cultural obstacles to testing, setting up all-female teams and offering a range of other health tests as well as vaginal examination. After eight years, they are succeeding in finding early-stage pre-cancers that can be easily treated.

In pieces for radio, newspapers and the Internet, Silberner found the positive as well as the negative and focused on the role of the local health teams in leading the bid to diagnose and treat cancer, with support from partners in the US.

Hundreds of public service radio stations broadcast The World from PRI, and Silberner’s reports also ran on the BBC World Service website, where they received an enormous number of hits. Silberner has been very encouraged to see how much interest they have aroused. “The way that cancer is explored in the media here in the US is in terms of new high-tech treatments, the cost of treatment, and people who cannot afford treatment or drugs. It is not the developing world issue.

“Just talking about the issues is really important to people working on cancer in developing countries, because it is tough trying to get a programme going if nobody seems to care. The series told people in the field that this is a subject people are learning about.”

Some Ugandan languages still have no word for cancer, but awareness is growing and so are treatment options

Stories from the frontline

Silberner’s series on Cancer’s New Battleground gave doctors and patients the chance to tell the story of the suffering that cancer causes in developing countries and the low-tech cost- effective ways they are finding to help tackle it. Cancer World, published by the European School of Oncology, promotes the need to address cancer in low- and middle-income countries, as this is where almost two-thirds of cancer deaths occur. In a further recognition of the role of the media in making this health challenge a priority, ESO judges gave special merit awards to two African journalists: Esther Nakkazi from Uganda, who reported on innovative ways to communicate health information, and Busani Bufana from Zimbabwe, who also highlighted the desperate need for pain relief.

Shining a light on unreported suffering

For Silberner, the Best Cancer Reporter Award was one of a clutch of prizes related to her work. Together with her producer and editor David Baron, she received the TV and radio award from the US National Academy of Sciences, “for shining a light on the hidden toll cancer takes in impoverished nations”. Silberner also shared the 2013 Victor Cohn Prize for Excellence in Medical Science Reporting from the Council for the Advancement of Science Writing for her consistent record in “recognising new angles in important stories rather than offering stories that everyone else covers”. The World pieces were a major factor, cited for “sparkling story-telling and the human dimensions”.

Silberner came to journalism late and reluctantly. Her ambition was to be an endocrinologist and study the beauty of hormones. She studied at Johns Hopkins and was delighted that she did not have to write essays to get in. “I had no intention of writing ever,” she says firmly. In her final year, she had to add one extra module and “completely by accident” added a course in scientific writing. Despite praise and support from her professor, her professional experience was limited to writing the labels on fish tanks during an internship at the Scripps aquarium in San Diego! After a spell analysing health and scientific bills for the California state government, she accepted her destiny and went to journalism school. After graduation, she reported on science for magazines before joining National Public Radio.

Silberner is still committed to neglected health topics, recently researching stories about diabetes and high blood pressure in Cambodia. So will she write further about cancer? “I would love to. I just have to figure out a way to do it and for somewhere to publish my stories.”

The good news is that Silberner does not just write and broadcast. She also now teaches journalism at the University of Washington – inspiring others to find and tell neglected stories.