With studies showing that around half of all cancer patients use therapies that are not part of mainstream medicine, Cancer World Editor Alberto Costa explores some aspects of the discussion on what complementary and integrative medicine can offer cancer patients, and the supporting evidence behind a range of options.

Cancer patients have been turning to complementary and integrative medicine in ever increasing numbers over recent decades. A survey published in 2005 found that levels of use varied across Europe, with around one in four cancer patients using complementary or alternative therapies in countries with the lowest use, rising to three in every four patients in countries with high use (Ann Oncol 2005, 16:655–63).

The term ‘complementary medicine’ is used to denote therapies that are used along with standard medical treatments but are not considered to be standard treatments. ‘Integrative medicine’ denotes a total approach to medical care that combines standard medicine with the complementary/alternative practices that have been shown to be safe and effective. They treat the patient’s mind, body, and spirit.

Integrative medicine is interdisciplinary, using the skills of several healthcare disciplines through referral and consultation. It emphasises using the individual’s capacity for self-healing in an approach that is personalised, collaborative and comprehensive.

The National Center for Complementary and Integrative Medicine (NCCIM), within the US National Institutes of Health, includes a range of therapeutic approaches under the heading of complementary and integrative medicine, many of which are listed in the table below.

NCCIM distinguishes between natural products and mind–body practices, and defines its own role as determining, “through rigorous scientific investigation”, the usefulness and safety of complementary and integrative health interventions and their roles in improving health and healthcare.

Complementary and integrative (CIM) approaches are more likely to be used by female patients, and those who are younger, white, more highly educated and on a higher income.

Patients use these types of therapy for many reasons, including improving physical symptoms, supporting emotional health, boosting the immune system and improving quality of life. Some patients use CIM to relieve the side effects of conventional cancer treatments or to obtain a more holistic treatment, while others may be hoping to gain better control of their disease.

CIM use in breast cancer

Women with breast cancer have particularly high rates of use of complementary, integrative and alternative therapies. The European Society of Breast Cancer Specialists (EUSOMA) published a report and recommendations on the use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) in caring for patients with breast cancer (Eur J Cancer 2006, 42:1702–10; ibid 1711–14; Eur J Cancer 2012, 48:3355–77). These recommend that all patients with breast cancer should be treated by multidisciplinary teams that provide the best chances of cure, palliation, and psychosocial and spiritual support.

The recommendations also suggest that clinical case histories and randomised trials should contain modules that identify patients’ belief systems about complementary and alternative medicine, and establish whether it is being used concurrently, and support open and factual discussions about it.

A study of the use and experiences of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) among breast cancer patients stated that the findings “underscore the results obtained in other studies, such as high overall use of CAM in breast cancer patients and the association of CAM use with younger age, higher education and more advanced clinical stages,” adding that, “This study clearly demonstrates the role of information sources outside the medical system, sometimes reinforced by negative experiences within the oncology speciality system,” (Eur J Cancer 2012, 3133–39).

“Given the prevalence of CAM use and the restraints patients felt,” the authors conclude, “every attempt should be made by oncologists to initiate communication about CAM pro-actively (including the provision of information regarding possible supportive options and cautioning about the potential harm of some of these therapies), rather than letting breast cancer patients slip into an alternative world seemingly detached from conventional medicine, where patients rely mainly on the advice given by other patients, family members and friends or on information extracted from the internet.”

Clinical practice guidelines have also been published on the use of integrative therapies in the supportive care of patients treated for breast cancer (JNCI Monographs 2014, 50:346–58), on the use of complementary therapies and integrative medicine in lung cancer (Chest 2013, 143 (5 Suppl):e420–36) and on exercise for cancer survivors (Med Sci Sports Exerc 2010, 42:1409–26).

CIM use in advanced disease: the case of pancreatic cancer

With so many new drugs being introduced into clinical practice to prolong survival in advanced cancer, the whole perception of metastatic disease is changing. From the passive resignation of the past, clinical oncology is moving to a point in which the fight against the disease continues well beyond the transition to the metastatic stage, no matter how much this will cost, both financially and emotionally for patients and their caregivers.

With the exorbitant price tag new drugs attach to every additional month of survival, it may be expected that people will increasingly turn to alternatives in the hope of obtaining similar results. One potential candidate will be mistletoe which, alongside other natural compounds such as curcumin, has been used medicinally for thousands of years and is a key part of some complementary/alternative practitioners’ armoury.

A quite surprising paper on mistletoe (Viscum album extract) in advanced pancreatic cancer was quietly published a few years ago by the European Journal of Cancer. This is the official journal of EORTC (European’s leading cancer clinical trials organisation), EUSOMA, (the European Society of Breast Cancer Specialists) and ECCO (representing Europe’s professional cancer societies), whose editor in chief, Lex Eggermont, has a strong reputation for both his rigorous scientific approach and his attention to the emerging field of immuno-oncology in advanced disease.

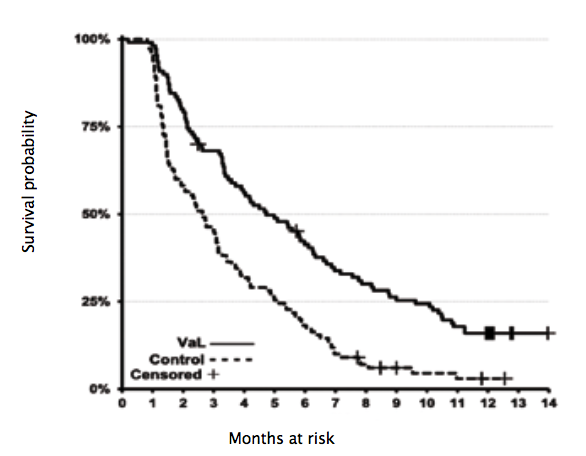

The paper describes a significant survival benefit in a prospective randomised phase III trial in 220 patients with locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer, with a median overall survival of 4.8 months for patients receiving Viscum album L extract compared with 2.7 months for patients on no anti-cancer therapy

(HR 0.49, 95%CI 0.36–0.65) (Eur J Cancer 2013, 49:3788–97; see figure above).

On the other hand, a very recent statement by the US National Cancer Institute’s PDQ (Physician Data Query service), updated on February 2017, states: “The use of mistletoe as a treatment for people with cancer has been investigated in clinical studies. Reports of improved survival and/or quality of life have been common, but nearly all of the studies had major weaknesses that raise doubts about the reliability of the findings. At present, the use of mistletoe cannot be recommended outside the context of well-designed clinical trials. Such trials will be valuable to determine more clearly whether mistletoe can be useful in the treatment of specific subsets of cancer patients.”

Flashpoints in the CAM/CIM debates

While the potential of mind–body therapies such as Tai chi, meditation and massage to improve patient wellbeing attracts little controversy, the same cannot be said for all complementary and alternative therapies.

Alternative or complementary?

The key message to cancer patients is that using alternatives to standard proven therapies to treat the cancer is extremely risky – Cancer World has republished two articles by Bernhard Albrecht, a German doctor-journalist who investigated the tactics used by people who promote these sorts of ‘alternative anti-cancer treatments’ (‘In the jungle of the miracle healers’, Cancer World 50 Sept–Oct 2012, ‘Dangerous healers’, Cancer World 69 Nov–Dec 2015).

Complementary therapies, by contrast, taken in addition to standard approved anti-cancer treatments, could be beneficial or ineffective, but they could also be harmful if they interact biologically with the standard treatments. The advice to patients is: “Always inform your doctor about what else you are taking,” – and the advice to doctors is: “Take the initiative in opening up that conversation.”

Homeopathy

The scientific rationale behind homeopathy, an approach based on the principle of ‘curing like with like’, and involving the use of highly diluted substances, continues to attract particular controversy.

The most authoritative agencies and medical organisations in the world agree that there is currently no good evidence to show that homeopathy is effective.

Cancer Research UK notes on its website that homeopathy is one of the most common complementary therapies used by people with cancer, but advises that, “Although there have been many research studies into homeopathy there is no scientific or medical evidence that it can prevent cancer or work as a cancer treatment.”

The role some homeopaths, among others, play in promoting an anti-vaccination agenda has attracted particular controversy (Focus Altern Complement Ther 2011, 16:110–4), though the British Homeopathic Association, for instance, states on its website that “immunisation should be carried out in the normal way using the conventional tested and approved vaccines,” (www.britishhomeopathic.org/media-centre/vaccinations-statement).

A similar charge is also laid against some in the anthroposophic medicine community, whose voices have been heard alongside elements in the homeopathic community in recent vaccine debates.

A complicating factor

Some aspects of anthroposophic and homeopathic philosophy have been used by opponents of vaccination to justify their assertions. Concerns that engaging on a scienti c level with certain strands of complementary and alternative practitioners could be presented by the anti-vaccine lobby as lending credibility to their arguments can be a deterrent to dialogue.

Opponents of vaccinations often support their position by citing a 1999 study published in The Lancet (vol 353, pp 1485–8). The study found a significant trend (P=0.01) for an inverse relation between the number of anthroposophic lifestyle characteristics (including fewer vaccinations) and a reduced risk of atopy (tendency to allergic diseases) in children. The credibility of the paper has been questioned by some who argue that the decision to publish the study was influenced by the fact that Prince Charles, heir apparent to the British throne, is a follower of homeopathy and anthroposophy, and that he supported some research on the topic.

However, in 2005 the same journal published an issue with a cluster of articles accompanied by an editorial entitled ‘The end of homeopathy’, calling for “doctors to be bold and honest with their patients about homeopathy’s lack of benefit, and with themselves about the failings of modern medicine,” (vol 366, p 690).

Selling remedies without evidence

More than a few of our readers will certainly remember that many thousands of breast cancer patients were treated with high-dose chemotherapy supported by bone marrow transplantation as a result of a trial that was later found to contain false data from one of the collaborative centres.

And more than one centre treated breast cancer patients with intraoperative radiotherapy (IORT) long before the relevant randomised clinical trials were finished. As it turned out, the conclusions of the trials were negative, so those centres are no longer using IORT. The upshot, however, is that patients received an unproven treatment, which they even had to pay for themselves, as public healthcare providers, rightly, do not reimburse unproven treatments.

The list continues, as does the number of ‘scientific’ papers that are published and subsequently retracted, because of their flawed or fraudulent data – with high impact factor journals no less guilty than the rest. (More details of article retractions can be found at http://retractionwatch.com/ together with information about the worryingly high number of retracted papers that continue to be cited in the literature.)

So, the first important conclusion that can be drawn on this complicated issue is that we need to engage with the science rather than simply engaging in battles of references and counter-references.

The case of curcumin is emblematic: highly publicised in the media all over the world, it was recently classified as both a PAINS (pan-assay interference compounds) candidate, and an IMPS (invalid metabolic panaceas) candidate. “The activity of curcumin in vitro and in vivo has been tested in >120 clinical trials of curcuminoids against several diseases,” says the American Cancer Society website, “but no double-blinded, placebo controlled clinical trial of curcumin has been successful,” (http://bit.ly/ACS_curcumin).

True, say those convinced of the potential of curcumin, but you should give us the time to see whether it will be more effective when put in formulations such as liposome, and standardised, turning it into a modern drug, like many others that originate from plants.

The second conclusion is that it is too late, and too simplistic, to just ignore complementary and integrative medicine.

The World Health Organization recently published a document outlining the strategy for traditional and complementary medicines for the period 2014–2023, which can be found on the WHO website.

The document has the twin objectives of supporting Member States in enhancing the contribution of complementary medicines to health and wellbeing and at the same time promoting the safe and effective use of such medicines, by regulating professional products and skills. It asserts that, “These goals will be achieved by defining national policies, reinforcing safety, quality and effectiveness with regulations and promoting universal health coverage by integrating complementary medicines into national health systems.”

Several well-established cancer centres across the world have departments dedicated to complementary and integrative medicine, which is seen, by both patients and doctors, as an endorsement of the general approach – but not of every treatment that is included under the broad umbrella term of CIM.

Opening up the debate

□ We need to engage with the science rather than simply judging papers on where they come from or where they are published.

□ It’s too simple and too late to ignore complementary and integrative medicine.

□ Discussions about combining mainstream medicine with other approaches to health, cure and wellbeing are already widespread and increasing.

□ This is not ‘us versus them’, it is about empowering patients to make informed choices.

The Integrative Medicine page on the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center spells out their approach: “At Memorial Sloan Kettering, we believe in caring for the whole person – not just the disease or symptom. Integrative medicine weaves natural treatments such as acupuncture, massage, and yoga into your overall care plan. All of our holistic health services and programs are based on the latest scientific evidence.”

Europe’s largest public sector centre for integrated medicine is The Royal London Hospital for Integrated Medicine (RLHIM), which is part of University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust.

Formerly known as the Royal London Homeopathic Hospital, their website states that: “the RLHIM offers an innovative, patient-centred service integrating the best of conventional and complementary treatments for a wide range of conditions. All clinics are led by consultants, doctors and other registered healthcare professionals who have received additional training in complementary medicine.” The University of Exeter, also in the UK, has a chair in Complementary Medicine, currently occupied by Edzard Ernst.

So a possible third conclusion is that efforts to combine the various approaches to health, cure and wellbeing can be seen in many settings and countries. The key requirements seem to be the quality and level of knowledge of the professionals involved and – as in every human field – the level of intellectual honesty.

The fourth and final conclusion (and this is a very personal view) is that at the end of the day what is really needed is more patient empowerment.

Only someone who is lucky enough to have never experienced the panic and angst generated by a diagnosis of cancer (or other life threatening condition) can contemplate ignoring complementary and integrative medicine.

It is easy for a doctor to dismiss it as unproven quackery, but very difficult then to give an answer to cancer patients in pain, with impossible nausea and vomiting, with drug-resistant permanent insomnia, with weight loss and cachexia, who are open to any reasonable solution in the hope of feeling better.

Complementary and integrative approaches*

□ Aromatherapy

□ Chiropratic/Osteopathy

□ Hypnotherapy/Guided Imagery

□ Yoga/Meditation

□ Massage

□ Music and Dance therapy

□ Biofeedback

□ Ayurvedic medicine

□ TCM [Traditional Chinese Medicine] – Acupuncture

□ Homeopathy

□ Phytotherapy

□ Qi gong – Tai chi

□ Reiki

□ Re exology

□ Diet Supplementation*Some of the treatments included in the CIM definition used by the US National Institutes for Health NCCIM (https:// nccih.nih.gov/health/integrative- health#integrative)

Anyone who has practised oncology in an outpatient clinic in Europe or the US has seen, and should in fairness admit, that CIM can play a role for some patients and for some conditions.

We welcome contributions on this topic based on science, but not pseudo-science.

Please post your comments in the comments box below.