No longer children and not yet adults, adolescents and young adults with cancer represent a specific patient population posing outstanding challenges to oncologists all over the world.

Challenging but rewarding. This is how physicians described their experience of treating adolescents and young adults (AYAs) with cancer in a survey run during the 2019 Annual meeting of the European SocieTy for Radiotherapy and Oncology (ESTRO). “Adolescents with cancer, first of all, are adolescents. With their needs and their unicity that cancer is influencing but not erasing. And the same is true for young adults” David A. Walker, Professor of Paediatric Oncology, University of Nottingham, UK, said in his teaching lecture at the ESTRO38 Congress. Beyond psychology and behaviour, this unicity pervades even the clinical and bureaucratic sides of managing cancer in AYAs and should be taken in to account to properly and effectively treat these patients.

Who are we talking about?

The first issue to address when talking about AYAs is the definition of this population. This is a crucial step in order to collect more accurate epidemiological data and, consequently, to define appropriate strategies for screening, treatment and follow-up. The age range of 15-39 years is increasingly accepted for AYAs grouping, with adolescence set between the age of 15 and 19 years. According to this definition, AYAs represents approximately 40% of the world population with 1 million new diagnoses of cancer estimated in AYAs every year at the global level (Pediatr Blood Cancer 2017, 64(9):e26528; JAMA Pediatr. 2016, 170(5):495-501). “At present, almost one-third of the European population, but only 2%-4% of all European cancer patients would fall into the 15-39-year-old category. Even so, the EUROCARE-5 study observed an annual incidence of 50,000-70,000 new AYA cancers in Europe per year” stated Stefan Bielack, head of the Department of Paediatric Oncology, Haematology, Immunology at the Stuttgart Cancer Center, Klinikum Stuttgart-Olgahospital, Stuttgart, Germany, and Co-Chair of the ESMO-SIOPE Joint Working Group on Cancer in Adolescents and Young Adults. Moreover, in high-income countries (HICs) cancer remains the most common cause of disease-related death in AYAs, although the survival rates now exceed 80% for all diseases at five years in many of these countries, including the United States, Canada and Western Europe (JAMA Pediatr. 2016, 170(5):495-501). Noteworthy, a “survival gap” for AYAs was reported. “Historical epidemiologic data in HICs recorded modest or no improvements in the survival rate for AYAs over the years, and consistently lower gains in survival rates for AYA as compared to children for most cancers”, experts wrote (Pediatr Blood Cancer 2017, 64(9):e26528; Lancet Oncol. 2016, 17(7): 896-906).

Same name, different disease?

Cancers in AYAs are different from cancers in children and in older adults even when, at least by name, the disease is the same. “Adolescence and young adulthood represent the period of transition from childhood to maturity. This is reflected in the nature of the malignancies which AYAs experience” Bielack said. “Younger adolescents often suffer from cancers also observed in childhood, while a strong shift towards carcinomas occurs with increasing age” he added. Looking at different cancer types across the total AYA cohort (EUROCARE-5), breast cancer (18%), melanoma (14%), germ cell tumours (13%), female genital carcinoma (11%), thyroid cancer (7%), Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphomas (7% and 5%, respectively) have the highest incidences (Karger, 2016, 43: 1–15). Some malignancies, particularly bone sarcomas, germ cell tumours, and Hodgkin lymphoma, even have their age peaks in AYAs.

“There is a correlation between tissue growth and tumour incidence in the early ages. Lymphatic leukaemia is an example: it’s the most common cancer in younger patients with the curve representing the number of cases per year almost perfectly overlapping with the curve representing the growth of lymphatic tissue” Walker explained. Furthermore, AYAs cancers show unique biological/genomic features compared to cancers in children and older adults, partially accounting for differences in clinical outcomes and resistance to treatment (The Cancer J. 2018, 24(6): 267–274). In this complex scenario, the question arises on whether AYAs with cancer should be treated with paediatric or adult protocols. “It was clearly demonstrated that AYAs with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia can strongly benefit from ‘paediatric type’ treatments so that paediatric regimens are nowadays considered standard ALL-therapy even in adult oncology departments. On the other hand, young patients with colon cancer or other typical ‘adult’ malignancies will achieve better results if treatment decisions are not made solely by paediatricians” Bielack stated. “In the end, it is all about working together and building platforms which provide access to adequate interdisciplinary and multi-professional care” he concluded.

A plethora of transitions and challenges

AYAs live in an age of transitions, both from physical and psychosocial points of view, making it harder for them and for physicians to cope with their cancer “journey”. One of the most important challenges in treating AYAs with cancer is the delay in diagnosis: in this age group, cancer is often diagnosed at a later stage than in adults or younger children and there are several reasons behind this. Most young people do not have health concerns and other interests (school, friends, work, partner) take priority over health. Moreover, generally speaking, a failure in recognising the importance of a symptom can occur, mostly because cancer does not rank first in the list of possible causes of symptoms like pain or tiredness in AYAs (American Cancer Society; Pediatr Blood Cancer 2017, 64(9):e26528). Once cancer has been diagnosed, many other specific issues should be addressed in AYAs. Adherence to treatment is one of the most challenging, with studies demonstrating that these patients – adolescents in particular – do not comply well with the treatment, often leading to poor outcomes. In this context, attention should be focused on communication, events through social media and Internet use, as the constant presence on these media discriminate AYAs from other age groups (Adolesc Health Med Ther. 2018, 9: 77-85). Sexuality and oncofertility also have a specific and outstanding role in caring for AYAs with cancer. The first is strictly related to changes in body image and self-esteem due to the disease and its treatments, while the second is particularly important for people in their reproductive age. Cancer treatment can, in fact, impair fertility with deep consequences also on a person’s psychosocial wellbeing, so that specific guidelines have been published on fertility preservation in patients with cancer and tools have been developed to tackle reproductive concerns of young women (JAMA Pediatr. 2016, 170(5):495-501). Last but not least, the development of late side effects should be carefully addressed in AYAs with cancer. As reported by Barr and colleagues, information on the long-term effects of therapies is limited in this population, but it’s known that those late side effects are prevalent and can compromise the quality of life and also reduce life expectancy. Managing these effects, including the possible risk of second malignancies, is crucial and there is not a one-fits-all solution when defining principles to be considered. “Among these are the fostering of autonomy in survivors and responsibility for their future health…This is aided considerably by the provision of a survivorship care plan” Barr wrote (JAMA Pediatr. 2016, 170(5):495-501).

Staking out the right to quality care

Access to quality cancer care is a right, not a privilege, and it’s important to improve services and support to young people diagnosed with cancer, regardless of geographical location. It’s written in the International Charter of Rights for Young People with Cancer, a global initiative launched in London in 2010, with more than 10,000 signatures collected in less than 6 months (J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2011, 1. 49-52). Despite the words written in the Charter, a recent ESMO/SIOPE survey on 266 European healthcare professionals clearly demonstrated that “There are important underprovision and inequity of AYA cancer care across Europe”. According to the results, 67% of participants did not have access to specialised centres for AYAs, while 69% did not know about research initiatives on AYA cancer patients. In addition, 67% had no access to specialist services for late effects management and 38% declared that their patients did not have access to fertility specialists (76% in Eastern Europe). “Improving care through education and research focused on AYA should be a priority” authors concluded (BMJ Open 2017, 2: e000252).

The value of specialised care

“The thought of having to face my battle with cancer alone, without my friends around me really scared me… Just knowing that there was a room full of people my age who had been through cancer put a great deal of hope back into my life” Fiona, a 17-year-old patient with non-Hodgkin lymphoma said (J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2011, 1. 49-52). As a matter of fact, the debate is still open on which is the best place for an AYA with cancer to be treated and there’s a real risk for these young patients to fall into a “no man’s land” between paediatric and adult wards or hospitals. “Adolescents feel lost in paediatric playrooms; young adults find themselves on wards which are better suited for geriatric patients” Bielack noted. Underlining this, “any given institution should only treat AYAs with cancer if there is sufficient experience in taking care of the malignancies which affect young people and if it has the multi-professional infrastructure in place to address their specific needs”. So far, as Bielack added, this is often not the case even if some European countries have witnessed centralisation of their AYA oncology into dedicated AYA units over the past decades. The UK was one of the first countries to recognise that AYAs’ needs were poorly met by conventional health and hospital services in the late 1980s, when specialised care units were set in several hospitals, which served young patients of different age groups (Pediatr Blood Cancer 2017, 64(9):e26528). More recently, the BRIGHLIGHT programme of research was started to evaluate if a dedicated teenager and young adults (TYA) cancer service could really improve outcomes in people aged 13–24 years diagnosed with cancer in English hospitals. At the completion of data collection in March 2018, longitudinal comparisons have started to determine outcomes and costs associated with being treated in specialised centres. “Findings will inform international intervention and policy initiatives to improve outcomes for young people with cancer” Rachel M. Taylor and colleagues wrote in a paper published earlier this year in the BMJ Open (BMJ Open 2019, 9: e027797).

In touch with adolescents: the HEEADSSS interview framework

A strong patient-physician relationship is crucial for successful interaction with AYAs patients, especially adolescents, and there are some “rules” every doctor should consider in his/her clinical practice. “Never try to be cool with an adolescent. Just be yourself” David Walker advised, stressing the importance of confidentiality in this specific communication setting. The HEEADSSS structured psychosocial assessment has been proposed as an effective tool to address young patients’ needs and concerns and to build bridges between doctors and patients (Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2018, 103: 15-19). Eight steps and topics are included, from the general “Home” (the environment where they live) to the tricky “Safety” (how they cope with danger):

- Home

- Education/Employment

- Eating

- Activities

- Drugs

- Sexuality

- Suicidal ideation

- Safety

Breaking the “18-years-dogma”

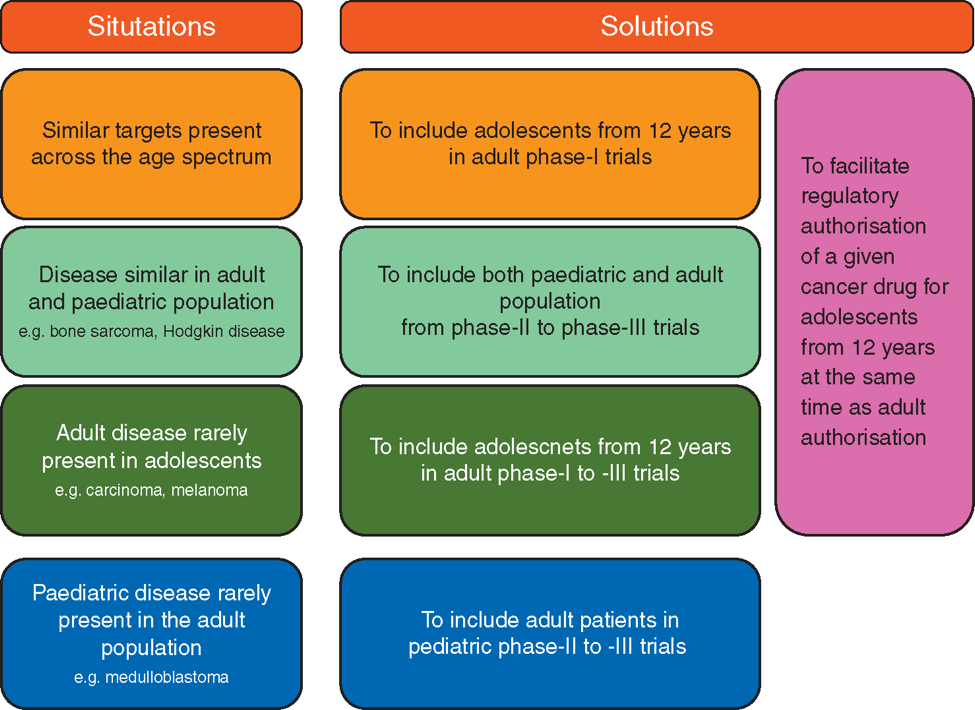

“When you look at a graph of the age-specific incidence rates of cancer in the population, you should think that there’s no need to address cancer before the age of 25” David A. Walker provocatively said during the session dedicated to AYAs at ESTRO38. “And this attitude has provided resistance to development in the field in the last 30 years” he added. However, the small number of cancers in AYAs as compared to the older population is not the only reason why studies specifically focused on this age population are scarce. “Some investigator-initiated trials, most notably those of the international multi-institutional bone sarcoma groups, have a long tradition of recruiting children, adolescents, and young adults into the same studies. All too often, however, ‘paediatric’ and ‘adult’ trials will only enrol patients on either side of an arbitrary 18-year age barrier. The latter is particularly troublesome when it comes to industry-led development of new agents. All too often, early trials are still limited to adults while adolescents are excluded from enrolment without any sound biologic rationale” Bielack commented. The ESMO/SIOPE Working Group on cancer in AYA has already addressed the topic by means of an e-learning module led by Nathalie Gaspar, Head of the AYA unit at Gustave Roussy Cancer Campus (Villejuif, France). The expert underlines that the progress recently obtained in adults by the introduction of new drugs has not yet been observed in adolescents, mainly due to the fact that “the current drug development landscape separates adult and paediatric drug development” (Annals Oncol 2018, 29(3): 766-771). Many examples are now available on how this exclusion or improper inclusion in clinical trials has led to a delay in the availability of new treatments for AYA, even when the biological or molecular characteristics of the disease supported a possible indication for the drug in AYAs. The multi-stakeholder platform ACCELERATE has proposed changes to the European Paediatric platform in terms of AYAs accrual in clinical trials (Figure 1) to improve early drug access for this cancer population. “Despite common misconceptions, there are no legal or regulatory barriers to including adolescents in adult phase I/II trials and to including young adults in paediatric trials” she wrote, adding that “This approach is complementary to existing paediatric and adult drug development approaches and should not replace, or delay them” (Annals Oncol 2018, 29(3): 766-771).

Together towards a better care

National AYA initiatives are active in many European countries and there are multiple opportunities to obtain information on the topic. Some of them are listed below:

- European Network for Teenage and Young Adult Cancer (ENTYAC). The network includes the European national groups and both adult and paediatric caregivers are involved on the ENTYAC board.

- ESMO/SIOPE AYA Oncology Working Group. A joint dedicated to education formed by European Societies for Medical and Paediatric Oncology, ESMO and SIOPE. The group is also working on a concise AYA oncology handbook and the two societies hold regular AYA sessions at their respective annual conferences.

- The Journal of Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology (JAYAO). An international journal publishing papers about almost every aspect of AYA care on a regular basis.

- Opportunities to obtain in-depth information also include preceptorships as well as online postgraduate courses.