Oncologists put their faith in evidence-based guidelines. But when the treatment is multidisciplinary, who decides on the evidence and how? ECCOs new Guidelines Forum has come up with a plan.

Clinicians in most medical specialities do not lack guidelines for their day-to-day treatment of patients, and oncologists certainly have many to choose from at both national and international levels, issued by cancer societies and government healthcare agencies. Guidelines – if followed properly – can have a significant impact on outcomes, as they can help address the variations of clinical practice between countries and within countries, complement professional education, provide auditing and evidence for healthcare decision making, and provide patients with reliable information about standards of care. They have been widely issued for certain treatments where specialist knowledge from a branch of oncology is applied.

But there’s a big problem with much of the current guideline work, according to Dirk Schrijvers, head of oncology at the Ziekenhuis Netwerk Antwerpen (ZNA) in Belgium, and that is a lack of guidelines that bring together evidence in a multidisciplinary way, and which also conform to international standards for guideline development. That’s because so much in optimal treatment and care in cancer now depends on teams of professionals working together.

Schrijvers is chair of ECCO’s recently established Multidisciplinary Clinical Guidelines Forum, which was set up by the pan-European cancer society to help fill this gap in the guidelines by networking among oncology societies, and also promoting quality criteria that should extend across guidelines of all types in oncology.

“There is no doubt that cancer is becoming more multidisciplinary, with not only the various physicians involved in care but also nurses, psycho-oncologists and others too. But most current guidelines are uni-disciplinary, as cancer societies are mainly producing guidelines specific to their subjects,” he says.

That is not a problem, he adds, for situations such as a patient with metastatic disease where the main or only treatment path is with drug therapy. “Then specific guidelines for medical oncology are fine for clinical practice. But there are problems when there are several modalities involved in treatment, and here the uni-disciplinary guidelines often lack the multidisciplinary character.”

A key example is rectal cancer. “Depending on the stage of the cancer, you can give radio and/or chemotherapy, perform surgery and may need to provide follow-up care for temporary or permanent stoma – all these aspects and more need to be covered by a guideline.”

There are examples of multidisciplinary guidelines for rectal cancer, but they may not yet fit all the criteria that ECCO is proposing – and that health service funders are starting to demand, says Schrijvers. In the case of his own society, ESMO (European Society for Medical Oncology), which has a strong guideline development group, its current rectal cancer guideline is co-authored by a surgeon, a medical oncologist and a radiotherapist – but it is not a collaboration between European societies. Although there is a delegation procedure, it is an ESMO guideline, not a formal joint one that would also include ESSO and ESTRO (the surgeon and radiation oncologist societies) and possibly other organisations, such as EONS, the oncology nursing society. “Other guidelines have been produced by groups that do not have any endorsement from any cancer society,” says Schrijvers. “For high-quality multidisciplinary guidelines we are looking for involvement from all the relevant societies.”

“For high-quality multidisciplinary guidelines we are looking for involvement from all the relevant societies”

WHO IS DEVELOPING GUIDELINES?

This is a key aim of the Multidisciplinary Guidelines Forum, and was prompted first by the EU Eurocancercoms project which funded a survey in 2010, carried out by Schrijvers and colleagues, to find out which European organisations involved with oncology are developing guidelines. Thirty European cancer organisations were contacted, and 21 responded to the questionnaire. Of these, 13 were involved in the production of clinical practice guidelines. Almost all of these organisations developed guidelines for their members or their institutions, but more than half stated that their guidelines were also aimed at policymakers (53.9%). A majority have some multidisciplinary input, mainly from the medical specialties and nursing, and to a lesser extent from professionals in communications, social science, health economics, epidemiology, and statistics and informatics (a median of three to five disciplines were involved). Patient representatives were also involved by five organisations.

There was a wide variation in quality control in review, piloting and consensus procedures and, significantly, only a small minority required any methodological training for members of the guideline development group. The costs involved were considerable, at €25,000–50,000 for development and €5,000–10,000 for distribution for each guideline.

“Once we saw that there were so many guidelines being produced independently, we thought it could be possible to bring the societies together, specifically to improve multidisciplinary working,” says Schrij-vers. That led to the establishment of the ECCO forum and a working group, which first developed a consensus paper. The societies were then polled again on questions such as whether they have a system to contact other ECCO members for participation in guideline development, and on procedures and formats for guideline production (presenting guidelines as flowcharts, though rarely done, can help usability, as can producing different versions – short and long – and factsheets for patients).

COORDINATION NOT COMPETITION

COORDINATION NOT COMPETITION

There is one fact that Schrijvers wants to make clear: ECCO is not setting up its own guideline development group, as some have thought. “We want to be a platform or ‘switchboard’ for organisations to come to when they intend to produce a guideline – so they can ask for help in involving other societies to make it truly multidisciplinary,” he says. “There’s no doubt that oncology societies do an excellent job with their own guideline development groups – we are not opening up the process to competition.

“We want to be a platform or ‘switchboard’ for organisations to come to when they intend to produce a guideline”

“So far, we have issued the consensus about how we want to proceed, and have also prepared a statement paper that outlines the multidisciplinary guideline process. The next step is to make it operational.”

Apart from European societies, there are also national guidelines produced by agencies such as INCa in France and NICE in the UK, and many more by national oncology societies, but Schrijvers says there is a distinction to be made between these and European guidelines. “Ours is a European effort that we are putting forward based on science – an issue with national guidelines is that they are also often based on whether reimbursement is available for certain treatments and drugs, and on the resources of healthcare systems.

“There will always be these differences and we are not against that, but we need a standard that is the state of the art for patients.” It is the same approach, he adds, that ESMO has applied with its minimum clinical recommendations series, which was translated and distributed throughout Europe by 2002, with a particular aim of reaching central and eastern European countries.

Schrijvers notes, however, that with national health systems moving to evidence-based care, such as with mandatory multidisciplinary consultations, and requiring minimum numbers of procedures, guidelines are also being subject to quality criteria. In Belgium, he says, each hospital now has to maintain a book of guidelines that are mostly adapted from high-quality international guidelines (Belgium uses a methodology called ADAPTE to do this – see the Guidelines International Network for more information).

He recalls one meeting, at the Belgian national guidelines group for prostate and testicular cancer, where he suggested including an ESMO guideline as a source, but it was pointed out by the Belgian Healthcare Knowledge Centre (KCE) that it didn’t at that time comply with AGREE (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation) – one of the most used international instruments for assessing methodological rigour and transparency – and so was excluded.

In the most recent survey of members of the ECCO forum, AGREE is now used by ESMO and others including ESSO and the European School of Oncology, but others such as ESTRO do not, although some have other quality evaluations. But a majority do at least use a development procedure based on recommendations from WHO, NICE and others.

The variability is echoed in the US – researchers at the University of Michigan Comprehensive Cancer Center recently looked at 169 guidelines for lung, breast, prostate and colorectal cancers and found that none fully met standards set in 2011 by the US Institute of Medicine (see the IoM’s ‘Standards for developing trustworthy clinical practice guidelines’), with the most common gaps being managing conflicts of interest and including patients or other lay people in the process. Co-author Sandra Wong does point out that for trustworthiness, some standards such as patient involvement may not be as important as, say, carrying out systematic literature reviews.

When it comes to multidisciplinary work, only four societies surveyed by ECCO have a system to contact other societies for involvement, which is one of the key reasons for the forum, says Schrijvers. “We are also finding some good systems from some organisations that could be implemented by others. The European Association of Urology (EAU), for example, has an excellent database for compiling and evaluating evidence.”

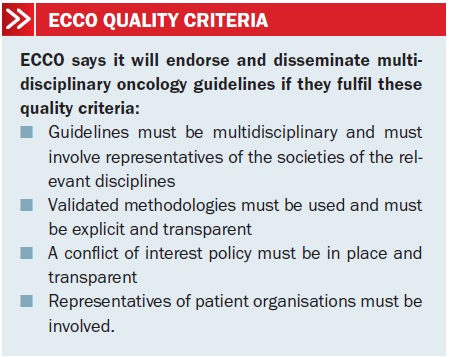

The ‘headline’ quality criteria that ECCO says should applied to multidisciplinary guidelines are straightforward and to the point (see box), and it intends to endorse guidelines that fit the bill. The type of work that should result in endorsed European multidisciplinary guidelines includes that of consensus groups, such as EURECCA colorectal, led by current ECCO president, Cornelis van de Velde, which has recently published a multidisciplinary mission statement on better care of patients with colon and rectal cancer in Europe (see Eur J Cancer 2013, 49:2784-90).

Only four societies surveyed by ECCO have a system to contact other societies for involvement

That’s a big and complex undertaking, but for a good example of a short, practical guideline that is in line with ECCO multidisciplinary aims, Schrijvers suggests the joint ESMO–EONS guideline on management of chemotherapy extravasation – the potentially serious problem of drugs leaking into tissue when they are administered. This is a collaboration between medical oncologists and oncology nurses – as EONS says, extravasations are a shared responsibility. It was published simultaneously in Annals of Oncology and the European Journal of Oncology Nursing in 2012… and it has flow charts.