Shared decision making is ethically sound and the evidence shows it leads to better outcomes. But if a patient is determined that they want no part in the decision, is it paternalistic to insist?

This article was first published in The Oncologist vol.19 no.4, and is republished with permission. ©2014 Alpha Med Press doi:10.1634/theoncologist.2013-0258

Mr C was an aristocratic, 79-year-old Surinamese man. He visited my outpatient clinic because of a pT4aN1a colon carcinoma. After surgery, he went to a rehabilitation centre, but he was improving day by day and was determined to get home as soon as possible. Given his high-risk colon carcinoma, he had an indication for adjuvant chemotherapy with capecitabine and oxaliplatin. However, adjuvant chemotherapy could also hamper his rehabilitation process. Together we extensively discussed the pros and cons of adjuvant treatment. Afterward, Mr C seemed quite certain: the increased chances of living without cancer outweighed the risk of side-effects of chemotherapy. Nevertheless, I suggested he think it over and discuss the issue with his relatives. Two weeks later, Mr C came in again, accompanied by his sister. Despite the hesitations of his sister (“Isn’t quality of life far more important than quantity of life?”), it seemed as if he was even more determined to start adjuvant treatment. His physical condition had remarkably improved, and, after he had received further oral and written information on the specific treatment regimen from our oncology nurse, we decided to start chemotherapy.

When I saw him after the first course of chemotherapy, he looked quite well. When I asked him about the past three weeks, however, he told me they had been awful. Mr C was in serious doubt: with respect to his chances of survival, he wanted to go for the maximum, but this reduction in quality of life was really not what he wanted. Although I could not pin down the exact toxicity he had experienced, the message was clear: he was not going to complete adjuvant chemotherapy in this way. For a moment, I considered a dose reduction of oxaliplatin, but then decided to propose stopping oxaliplatin altogether. The added benefit of oxaliplatin to capecitabine in patients older than 70 may be limited,[1] and oxaliplatin presumably was the major cause of my patient’s feelings of weakness and reduced walking ability. Also, I had the impression that the next course would be ‘make or break’. If it did not go well, he would probably completely stop his adjuvant treatment, which would be a pity given his wish to go for the greatest chances of survival. Mr C and his family agreed to continue with capecitabine monotherapy.

I saw Mr C and his sister again four weeks later. In fact, he was one week late; he had accidentally extended his capecitabine-free period by one week. Nevertheless, he told me he felt terrible: he had lost weight and was using his cane to walk. He actively announced he wanted to reconsider chemotherapy. I asked him to step on the scales: 64 kg. This was exactly the same weight as when he started chemotherapy. Why then was Mr C telling me he had lost weight? And why did he complain about walking with a cane? He had been walking with a cane all the time! Again, Mr C reported side-effects of chemotherapy that I could not really confirm. How to continue? A dose reduction of capecitabine might help, but by extending his capecitabine-free period, Mr C had already effectively performed a form of capecitabine dose reduction. Was a further dose reduction going to help him? I did not think so. Wasn’t Mr C actually telling me he wanted to stop the treatment? I asked him so. He denied this. Stopping was not really what he himself wanted to suggest. He wanted to know my expert opinion. I explained that in his case the choice to stop or to continue treatment was not just a medical decision but a decision that needed input from his side, too. Technically speaking, I had no formal reasons to stop adjuvant chemotherapy. Mr C was clinically well, laboratory results were within acceptable limits, and there were no grade 2 or higher toxicities, so if Mr C wanted to continue, we could continue. But Mr C insisted, “You are the expert”. I paused for a moment. What was going on? Why did Mr C not simply tell me he wanted to stop, rather than insisting on my medical expertise? I decided to change gears and asked him how a decision to stop treatment would make him feel. When he swiftly responded, “Relieved,” I simply made the decision to stop.

We talked a couple of minutes more about the logistics of follow-up. Then, Mr C and his sister left the room – relieved.

I stayed behind – confused and irritated. Why had I made this decision when I feel so strongly that this kind of decision making should be shared between a doctor and a patient? Being trained in the age of patient’s autonomy and rights, shared decision making is a natural part of my consultation with cancer patients.[2] Across cultures, different decision-making models can be identified,[3] but, as a doctor in the Netherlands, I have a legal obligation to inform my patient adequately about the pros and cons of a treatment, and I cannot start treatment without the patient’s explicit consent.[4] Although some decisions concerning starting or stopping oncological treatment are clearly medically preferable (e.g. haematological grade 3 toxicity precludes continuation of chemotherapy), many decisions concern a clinical equipoise (i.e. options are equivalent and all appropriate). At this moment, both continuing and stopping adjuvant treatment could be considered appropriate for Mr C from a medical point of view. In such a case, the only adequate way to reach a decision seems to be through shared decision making. Apart from its ethical impetus, evidence indicates shared decision making improves patient outcomes.[5] So, why then did I not convince Mr C to share in the decision to stop his treatment? Should shared decision making sometimes be replaced by a doctor’s decision if the patient chooses not to share in the decision making? Or… could the whole process we went through be called shared decision making after all?

“Why had I made this decision when I feel so strongly that this kind of decision making should be shared?”

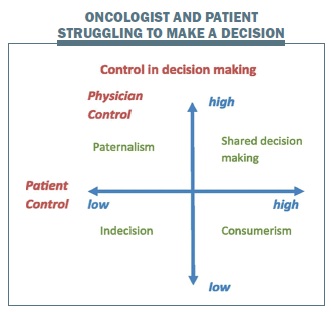

Based on the degree of patient and doctor control, theorists have identified four prototypes (or quadrants) of doctor–patient interaction.[6–8] When doctor control is high and patient control is low, the relationship is characterised by ‘paternalism’, whereby the doctor controls the consultation agenda, and patients’ values and preferences are not taken into account. For a long time, doctor–patient interactions could generally be characterised as paternalistic. If, in contrast, doctor control is low and patient control is high, one speaks of ‘consumerism’. The patient sets the agenda and takes sole responsibility for the decision; the doctor’s role is primarily one of information provider. In modern times, the societal image of a typical patient reflects such an autonomous, assertive, and well-informed consumer. If both patient and doctor control are low, a dysfunctional scenario of ‘indecision or standstill’ is at hand, and no decisions or progress can be made. Finally, if both patient and doctor have high control, this represents ‘mutuality’ or a ‘shared’ model. The agenda is set jointly, patients are told that there are equivalent options, appropriate information is given based on the doctor’s expertise, the patient’s values and preferred role in decision making are explored, and eventually both parties are satisfied with the decision-making process and the eventual decision.[5,9] This is the prototype of the doctor–patient input that reflects shared decision making, as currently advocated.[10]

Clearly, in the case of Mr C, ‘consumerism’ was not an issue. Having the consultation ending in ‘indecision’ was not an option as, in contrast to palliative treatment, in adjuvant treatment the time frame is stringent. Despite my preferred ‘shared and mutual’ decision-making style, I felt as if I had ended up in the ‘paternalistic’ quadrant. Although Mr C had set the agenda to discuss the continuation of chemotherapy, and I had explored his values and preferences, in the end I made the final decision, and the ownership of that decision was shifted to my side. However, paradoxically, in a way, in the case of Mr C, shared decision making would have been paternalistic too, as I would have forced him into taking responsibility for a decision from which he seemed to want to defer.

“Shared decision making would have been paternalistic too, as I would have forced him into taking responsibility”

Why was it so difficult for Mr C to share in the responsibility for the final decision? Several barriers to shared decision making can be identified from the literature that may be categorised into the following: a ‘lack of competencies’ required to take part in the decision-making process; a ‘position of dependency’ in the patient–doctor relationship, hampering active involvement in decision making; and the ‘inability to cope’ with the burden of decision making. The modern focus on patient-centred communication requires a high level of communication competence from the care provider but also from the patient. Patients need competencies enabling them to ask questions, act assertively, and express their concerns and feelings.[11] It was shown that less-educated patients more often prefer a passive role in decision making.[12] Also, an exploratory study showed that lay people’s confidence in their understanding of cancer-related jargon was related to their perceived efficacy in participating in treatment decision making with a fictive oncologist.[13] Moreover, patients mention barriers to participation such as simply forgetting questions or not knowing how to interrupt the doctor.[14]

Mr C, however, was a well-educated, eloquent man, and competence may not have been a major issue. Possibly the second barrier – dependency in the patient–doctor relationship – played a role. A patient is in a vulnerable position and can feel too reliant to act assertively in interactions with oncologists. Often accompanying this feeling is a high motivation to trust the doctor.[15] This is supported by the finding that patients often report the fear of being labeled a difficult patient.[14] Although Mr C was actively invited to put forth his decision and was assured by the oncologist that his opinion was valuable to her, it cannot be excluded that this barrier still played a role, given Mr C’s pronounced respect for medical expertise.

Finally, patients may choose not to be involved in communication or decision making to protect themselves.[16] This can be a result of their general style of coping with adversity, for example, by ‘blunting’ or avoiding confrontation with information about adversity or denial.[17,18] Patients may anticipate and fear feelings of regret in the future and may be afraid to take on responsibility for a possible bad outcome of the decision, so-called anticipated regret.[19] Indeed, a larger role in the decision-making process may be related to anxiety in the two weeks following the decision.[20] Hence, making decisions can be a burden for patients. From an ethical perspective, clinging to the principle of autonomy in a liberal individualistic sense and forcing these patients into shared responsibility for a treatment decision may not be beneficial and thus directly in conflict with the ethical principle of beneficence.[21,22] Alternative ethical notions of autonomy exist in clinical practice, including the idea that the patient is entitled the wish not to participate, which is known as procedural independence or Socratic autonomy.[23]

Shared decision making suggests that in the process of decision making the patient and the doctor are partners who, ultimately, reach a decision for which the responsibility is shared. We advocate that healthcare professionals should do the utmost to lift the patient barrier of incompetence, for example, by avoiding jargon, providing written information, and actively inviting patients to ask questions and express their concerns and feelings, as well as to lift the barrier of dependency, for example, by making explicit that a patient’s opinion is valuable in the decision-making process. However, if patients are unable to cope with the burden of the ownership of the final decision, we should be willing to relieve this burden by offering to take on this responsibility. Likewise, to avoid running into paternalism, clarifying the patient’s preferred role in decision making as well as exploring the values that would have to be taken into account from the patient’s perspective is critical. In fact, by exploring the fears implicated in Mr C’s reluctance to share in the decision making and explicitly asking whether he wanted me to make the decision, both the ethical principle of autonomy and the principle of beneficence could have been done justice.

In conclusion, the emphasis of the last decades on patients’ autonomy and patients’ rights to make decisions regarding their medical treatment may have obfuscated the fact that, for a variety of reasons, patients may not be able to make a decision. We believe that, when striving toward shared decision making, the focus should be put on the steps taken to reach the final decision, rather than on the amount of ‘sharedness’ in the responsibility for the final decision. In this way, the role the patient wants is respected, and the patient’s values and preferences are taken into account. We advocate that an optimal medical decision is one that integrates information about the patient’s clinical state and circumstances, the available research evidence, as well as the patient’s values and preferences, including the patient’s preference regarding his or her role in decision making.[10]

Control and types of decision making

Patient’s initial active agenda setting Patient (P): So, I’ve a question for you – whether we can have another think about taking those pills – if I should continue or whether we can maybe do away with them completely, or maybe we can go for just the half – so that I would take 5 once a day instead of twice a day. That’s what I’d like to talk to you about. So that’s my suggestion.

Patient turning back once a final decision to stop is dawning Oncologist (O): Well, but if you are so clearly saying “this is not what I want,” then we should just stop.

P: Well I’m not actually insisting on that. I’m not pushing for that exactly, but that’s why, in consultation with you…

O: Exactly, but that’s just it… you’re not exactly insisting on this, but that’s what I think you’re saying between the lines – that that is really what you’d like…

P: Yes, uhm… yes… but you know how these things work, the medical science, and I don’t. I’m not medically trained, so you can also give me your evaluation. Apart from what I say – of course your opinion counts as well.

Patient’s explicit refusal to make the final decision

O: But do you… you’re actually giving even more reasons why we should stop.

P: Yes, but I still feel you should have the final say, because you know more about these matters than I do. You know more about chemical values and the results and the effects and the side-effects. I mean… I rely on your knowledge.

Oncologist changing gears

O: OK, but now I’m going to tell you that we’ll stop – but then what I want to know is how you’ll feel when you leave here. Will you feel relieved when you go out the door – or maybe secretly a bit sad? How will you feel when you go out of here?

P: Well I can tell you straight away – relieved.

O: Well, then the decision’s made – we’re going to stop.

P: But that’s with your conviction… Sister: Here we go again…

O: …with my conviction…

Acknowledgement

Hanneke W.M. van Laarhoven and Inge Henselmans contributed equally as first authors

Author affiliations

Hanneke WM van Laarhoven, Department of Medical Oncology, and Inge Henselmans and J (Hanneke) C de Haes, Department of Medical Psychology, Academic Medical Centre, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, the Netherlands