EORTC boosts efforts to address the long-term problems faced by people who have been treated for cancer.

The number of people who are living long lives after cancer treatment has been rising year on year, leading to a quadrupling of this population between 1975 and 2005, with an estimated 35 million survivors now living in the developed world. Yet interest in their needs has developed only recently.

One reason is that the issues faced by survivors vary greatly owing to differences in ages and cultures, and also different cancers and treatments. There is a wide spectrum of needs and priorities. Even the word ‘survivor’ carries different connotations for different people – some do see themselves as having battled through and are happy to have survived long after diagnosis and treatment, but others don’t want to be ‘labelled’ in a way that ties them to such a major event once they are told they are cured. Many people living with metastatic disease also reject the word as not reflecting their day-to-day lives.

Yet ‘survivorship’ is a term that has become widely adopted for a field of research on care and support for the phase of life that follows primary treatment to the end of life, or recurrence (different definitions are used), covering a wide spectrum of issues – health, psychosocial and economic – that are common to people who have been treated for cancer.

Most of these issues are still poorly recognised and, all too often, survivors are being left to try to organise the care they need on their own.

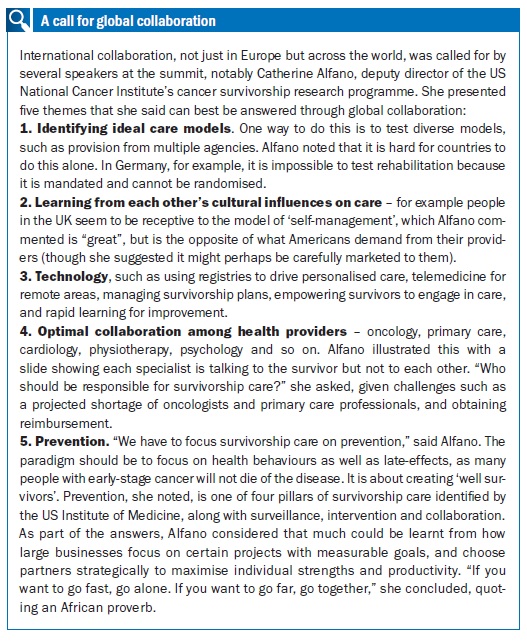

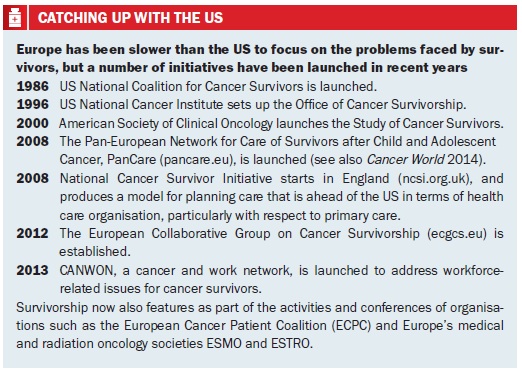

This is an area of research where the US took the lead and remains well ahead of Europe. But Europe is now beginning to catch up, with a number of important initiatives launched in recent years (see box overleaf), including the establishment of a collaborative group on survivorship, a network for survivors of child and adolescent cancers and the UK launch of the first national integrated programme to ensure every patient has their needs assessed and a care plan developed as their anti-cancer treatment comes to an end.

Most recently, the EORTC, which organises and coordinates clinical and translational research across Europe, stepped into the arena, launching its own cancer survivorship task force, and organising a two-day survivorship summit in Brussels this January.

Elizabeth Moser, chair of the task force, and head of radiation oncology at the breast unit of the Champalimaud Cancer Centre in Lisbon, outlined to the summit participants the nature of the challenge they are trying to address. “We have to spread information to clinicians, social workers and care givers. But do we have the information on the size of the problem – how many survivors there are and how many are at risk, and what we can do to avoid worse outcomes?” Much more data are needed to inform guidelines, said Moser, and although much has been done to reduce toxicities in cancer treatments, there is a big knowledge gap in long-term follow-up.

The good news, she added, is that there have been five decades of large-scale clinical trials, and data can now be collected from patients who underwent them. This, however, requires much greater organisation and communication across countries, and will be the biggest part of the survivorship research effort.

The task force is calling for collection of patient data from around Europe to provide the basis for developing prediction risk scores for late physical and mental effects. It also wants to collect information on current management of late-effects at national level, and promote broad networking among not only primary care professionals and patient advocates but also politicians, the insurance industry and economists.

“There have been five decades of large-scale clinical trials, and data can now be collected from those patients”

As a research organisation and a pioneer of quality of life measures, the EORTC is well-placed to co-ordinate research into late treatment effects from its clinical trials work, and it recognises the urgency of this work, as current information on late-effects is often hopelessly out of date. As Moser and colleagues point out in setting out the rationale for the survivorship task force, while there are well-documented serious late-effects from chemo- and radiotherapy, “the literature is focused on treatments dating from the 1960s to the 1980s” – and many of these are obsolete (Eur Oncol Haematol 2013; 9:74–76). “Little is known about combination of treatments, modern radiotherapy techniques, targeted agents, and hormonal treatments. Few studies have obtained data directly from patients and/or have considered preexisting co-morbidity, lifestyle, and obesity of survivors. There are few guidelines for the management of adult cancer survivors, and little is known about management and barriers in healthcare within different European countries.”

“Little is known about combination of treatments, modern radiotherapy techniques, targeted agents…”

Initially, the task force intends to look at the main physical late-effects such as heart problems and secondary cancers following certain common and rare primary tumours (in adults, not children) – lymphoma, breast, colorectal, prostate, gynaecological and testicular. However its remit will also cover a broader range of issues encountered by cancer survivors, including infertility and sexuality, cognitive dysfunction, and social impact, such as difficulties in obtaining work or insurance.

Early results

Moser reported on the initial survivorship research, in lymphoma trials. Questionnaires were sent to thousands of patients across Europe, which has so far resulted in published studies on semen preservation, premature ovarian failure, and parenthood. Analysis of factors such as radiotherapy dosing and impact on overall health, work, finance and more is yet to come. It’s a lot of work, she said, and needs to take into account sources of bias such as people who have died.

This work on lymphoma and also leukaemia survivorship is now informing solid tumour research. Moser mentioned a survivorship project on early breast cancer, which aims to update the results from six trials that took place between 1986 and 2011. Barriers must come down between tumour-specific groups, she said, because late-effects such as second malignancies and cardiovascular problems are often related to specific treatments rather than specific cancers.

A multidisciplinary effort will also be crucial in addressing issues such as fertility, cognitive dysfunction, and psychosocial functioning – the latter being the most complicated because of the variety of factors.

Can we also intervene in the lifestyles of survivors? Moser pointed out that it is particularly hard to influence younger people, who often drink and smoke, increasing their risk of developing problems later on. Other speakers emphasised that taking exercise, changing diet and making other lifestyle changes can greatly improve outcomes and/or quality of life, but noted that peers rather than health professionals are probably the best influencers. The American Cancer Society has drawn up nutrition and physical activity guidelines for cancer survivors, reported Catherine Alfano, deputy director of the US National Cancer Institute’s cancer survivorship research programme. She added, however, that while exercise and maintaining a healthy body weight are the best ways to tackle survivorship health problems, convincing someone with fatigue to take a walk can be hard.

Long-term data

Long-term data

The need for long-term data, especially on toxicity, was addressed by Connie Vrieling, a radiation oncologist from Switzerland. Looking at breast cancer, she noted how more patients are living with the consequences of treatment – “and if we stop at ten years in the follow-up of our trials we simply do not get the data.” As an example, she gave data from long-term outcomes from treating DCIS breast cancer with either excision or excision plus radiotherapy – and noted that a higher rate of secondary cancers in the radiotherapy group could call into question applying radiotherapy to all women. She also asked whether it is possible to get at data on risk factors such as smoking – in some places this is possible – and she mentioned the potential for gene expression and proteomic profiling from studies where tissue is stored.

“Use of radiotherapy to treat all DCIS could be called into question if data show it leads to more secondaries”

Researchers, health policy makers and advocates are not the only ones with an interest in long-term data on cancer survivors, however. Delegates at the summit may have been surprised to hear no fewer than three presentations from insurance and banking executives in the opening session. As the executives made clear, their companies need the data too so they can accurately reflect the risk they undertake in offering cancer survivors products such as life and travel insurance, and loans.

Insurers are major number-crunchers in their own right, as they collect information to inform their risk assessments. John Turner, of reinsurer Swiss Re, said that cancer is the cause of two-thirds of private critical illnesses payouts in the UK, and few claims are denied. But what about insuring people who have had cancer? “The problem is how we make it insurable – it is a serious threat to life. But we have to reflect the improvements in survival.” He charted how insurers model insurance applicants with a history of cancer, and how things have changed – the current recommendation for stage 1 breast cancer is to offer a standard premium after two to three years – whereas in 1995 that wouldn’t have been offered until after ten years.

Krish Shastri, chief executive of InsureCancer, a travel insurance firm that only insures people who have a diagnosis of cancer, said: “For us, survivorship starts from the minute of diagnosis to the end of life,” noting that for his business, it is hospitalisations that carry the most risk – and there are very few data on this. Travel for all sorts of reasons is crucial to quality of life, he added, and he appealed for more knowledge from aggregating European data that would enable better insurance underwriting to address the frustration voiced by many survivors about the lack of affordable insurance options.

Patient-reported outcomes

Lonneke van de Poll-Franse, professor of cancer epidemiology and survivorship at Tilburg University in the Netherlands, described how data can be collected on quality of life, with reference to the Eindhoven region where the cancer registry is used to send out questionnaires in an open access project called PROFILES – Patient Reported Outcomes Following Initial treatment and Long-term Evaluation of Survivorship. Patients are being asked about quality of life after a range of cancers and for specific conditions such as chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (see also Protecting Patients’ Nervous Systems, Cancer World 60, Cutting Edge). About 60% of patients aged under 50 in one sample reported problems in obtaining life insurance, for example.

As she added, by continuously monitoring the long-term impact of cancer and new therapies, registries become focused on patients, not just cancer. “By collecting data on patient reported outcomes, we can contribute to discussion on the added value of new therapies in daily clinical practice, and also socio-economic implications.” Other registries are doing the same, she said, citing a systematic review that looked at how this is a work in progress as a resource for survivorship studies (Cancer 2013, 119:2109–23).

Cancer registries can be used to send out questionnaires to collect data on quality of life

Kathy Oliver, from the International Brain Tumour Alliance, spoke on the input that advocacy can provide for the clinical trial community, affirming the need to build patient-reported outcomes into research, and mentioning biobanking as another area for collaboration with patient groups. She also added yet more items to an already long list of survivorship issues, such as the guilt often experienced by survivors, and she emphasised how important care plans are once main treatments ends.

An integrated national survivor plan

An integrated national survivor plan

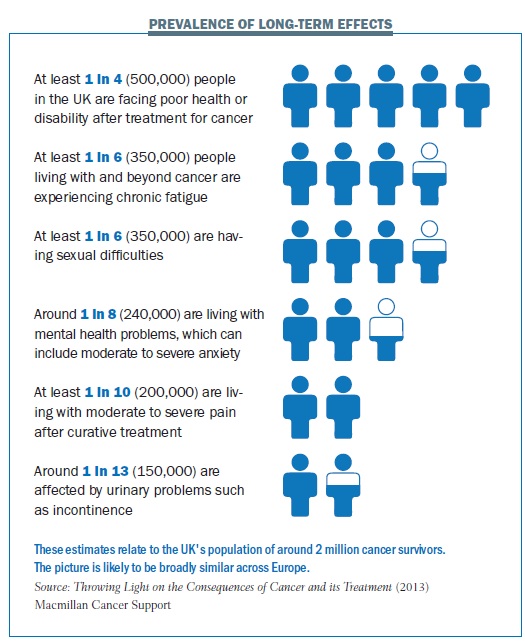

It was fitting that the UK’s approach to survivorship care plans was presented at the summit, given the lead the country is taking. Jane Maher, National Health Service improvement lead for cancer, said that by 2009 it was recognised that one in three patients had unmet needs by the end of their treatment, from a population of two million survivors. She outlined the stages between treatment and end of life – recovery, early and late monitoring, and progressive illness – and pointed out that differences between cancers means the timeframes for these stages can vary widely.

Central to the strategy, she said, is a recovery package surrounded by reviews, care planning, wellbeing events, financial support, and managing treatment consequences. These have been shown to help the majority of breast cancer survivors, and about half of survivors of colorectal and prostate cancer, into ‘self-management’ away from hospitals. To enable this, a holistic needs assessment is used to ‘shape a conversation’ at the end of treatment, from which a care plan is sent to the person’s GP. The GP then writes a treatment summary, which is a tool to improve communication between cancer services and primary care. Testing of both paper and electronic needs assessment has been underway for some time in about 200 hospitals.

Maher said it is a big challenge to change the perception of cancer from only being managed in acute settings to one where the outside community shares its perspective with specialists, and there are clearly major cultural and organisational differences among countries. One approach to care planning may not work elsewhere.

“It is a big challenge to change the perception that cancer can only be managed in acute settings”

The message from the summit is that cancer survivorship is on a steep learning curve and there is a long journey ahead, given the many issues and the rising numbers of survivors. But there are steps that can and should be taken now, such as combining current data and making it widely available, starting to plan for care, support and prevention, and collaborating both at European level and worldwide.