The principle of involving patients in decisions about their own care is no longer very controversial. The question is how you put that into practice when every option carries a level of uncertainty, patients may be feeling overwhelmed and none of the options may match their hopes or expectations.

Nothing about us without us’ has been the rallying call for cancer advocacy that has helped to expose the lack of patient voices in decisions about care and treatments. Since the 1990s, enlightened doctors and healthcare organisations, aware of the hierarchical nature of the physician–patient relationship, have joined the movement to better inform people so they can be part of decisions, and the result is that in many countries the picture has radically improved. There is no doubt that attitudes about truth telling and provision of information – as witnessed by the proliferation of patient decision aids and websites – have changed for the better.

In turn, this has led to the rise of shared decision making (SDM) – which is defined, briefly, as involving a patient in a decision to the extent they would wish by providing and discussing information about options. It has become a topic that has attained specialist status, at least when judged by the number of research groups, conferences and organisations reporting and adopting shared decision making.

In 2010 the Salzburg Statement on Shared Decision Making was agreed at a global seminar, which issued a call to clinicians, policymakers and patients to work together, and in the UK there has recently been a major push to embed this approach in care to “make no decision about me, without me, a reality”. There’s also a strong movement in the US to incorporate shared decision making into clinical practice, including by legislation in a few states so far, and some other European countries such as Germany have enacted a right to informed decisions.

Another word for good communication?

There is a debate about whether shared decision making is deserving of this status, or if it is really just one part of overall communications in patient-centred care. Psycho-oncology has, after all, pioneered much effective doctor–patient communication in cancer without using this terminology, while younger people, growing up in the communications age, are anyway driving a less formal and more informed culture from both patient and doctor viewpoints. But the term does focus minds on patient involvement – which all professionals with an interest in communications agree is still widely lacking and poorly practised in healthcare.

Shared decision making has a particular relevance in cancer because of the complex and profound decisions that often have to be made at various points in the cancer journey. But that complexity also poses a particular challenge in terms of presenting information to patients in a way that they can readily apply to their own specific situation.

As Ron Epstein, professor of family medicine, psychiatry, oncology and nursing, and director of the Center for Communication and Disparities Research, at the University of Rochester, New York, points out, there are simple situations where you hardly need a medical degree to consult with a patient, such as treating a urinary tract infection. “A decision about whether to have prostate cancer screening is more complicated – while there may not be one correct answer for everyone, there are a limited number of options and there is clinical evidence to guide decisions,” he says.

“But if someone has advanced colon cancer, it is hard to navigate. You can’t make a list of all the possibilities. Clinical evidence is lacking and often derived from populations that are different from this patient. Treatment regimens are changing. No one can predict what’s going to happen even in the next month, say if you give another line of chemotherapy. It’s more like navigating a ship through uncharted waters. It takes skill, but you often have to ‘muddle through’ – make provisional decisions, then take stock and make the next set of decisions.”

Those situations are especially difficult for oncologists to handle on a shared basis with patients, because of the lack of evidence about risk and treatments. Epstein has a particular interest in developing communications strategies in end of life care, where pursuing care that is unlikely to be effective is all too common despite attempts to foster more informed decisions.

But he makes the point that information is not enough. “There’s a view that if you provide people with enough information they will make wise decisions. The psychologists tell us it doesn’t always happen this way. Making choices about say surgery, radiotherapy or watchful waiting for prostate cancer is anxiety provoking. Patients can clearly be influenced by particular health beliefs and factors such as an oncologist subtly favouring one approach. And more information is not always better – sometimes patients get overwhelmed,” he says.

Shared decision making, Epstein notes, has grown up alongside the development of decision aids that aim to help patients understand the implications of such choices, which of course can be irreversible and with high stakes.

“Choices can be influenced by particular health beliefs and factors like an oncologist subtly favouring one approach.”

A stepped approach

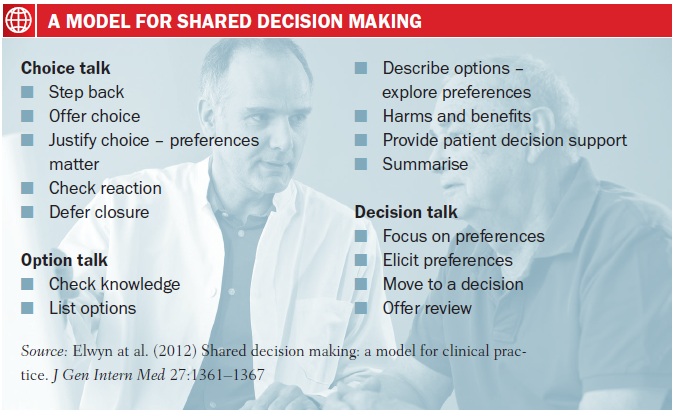

Providing information is one of two steps in ‘doing shared decision making’, as British expert Glyn Elwyn (at Cardiff University, Wales, and Dartmouth, New Hampshire) and colleagues put it in a paper on a model for clinical practice. “The first task of SDM is to ensure that individuals are not making decisions when insufficiently informed about key issues,” they write, noting that many tools have been designed to help achieve this goal.

The second step is to support patients to think about the options. “When offered a role in decisions, some patients feel surprised, unsettled by the offer of options, and uncertainty about what might be best,” they continue.

Adrian Edwards, a professor at the Cochrane Institute of Primary Care and Public Health (Cardiff Univeristy, Wales) with interests in risk communication and shared decision making, and a co-author of the paper, says: “The public don’t assume that doctors use SDM – they assume they get on and make decisions. Clinicians assume they are doing SDM but come to realise there is often much more they could do. Patients also assume there is a right answer and a right treatment and if a doctor is going through options they are kidding them – but in early-stage breast cancer, for example, there are genuine choices. So the first step is to make sure the patient understands there are key choices that they can make.”

Adrian Edwards, a professor at the Cochrane Institute of Primary Care and Public Health (Cardiff Univeristy, Wales) with interests in risk communication and shared decision making, and a co-author of the paper, says: “The public don’t assume that doctors use SDM – they assume they get on and make decisions. Clinicians assume they are doing SDM but come to realise there is often much more they could do. Patients also assume there is a right answer and a right treatment and if a doctor is going through options they are kidding them – but in early-stage breast cancer, for example, there are genuine choices. So the first step is to make sure the patient understands there are key choices that they can make.”

“The first step is to make sure that the patient understands there are key choices that they can make”

The simple model described in their paper, Edwards adds, shows how doctors can introduce shared decision making to their practice. “First is to introduce this idea of choice. Then you explore the options. Lastly, you focus on preferences that can move to a decision.” However, within these stages there is a lot to appreciate about truly giving patients the time and information to come to a preference, from checking reactions to choices and that information is understood, especially on the harms and benefits of the options, to deferring a decision where the patient isn’t ready. “And even if patients say they don’t want to be involved in decisions, they may want to later. You need to be aware of when people become more informed and confident.”

Decision aid tools for patients, he adds, are not essential, but there is growing evidence that they have a positive effect. A Cochrane review by Stacey Bennett and colleagues found that “decision aids increase people’s involvement, and improve knowledge and realistic perception of outcomes,” and can lead to people making more conservative choices, for instance, by not opting for surgery. “They also help options to be discussed in a standardised way, which can reduce the problem of healthcare professionals in different specialities saying different things,” says Edwards.

“Decision aids increase people’s involvement, and improve knowledge and realistic perception of outcomes”

The healthcare quality group at Cardiff University, which Edwards is part of, has developed a set of option grids for use by patients with their doctors to compare treatment and screening choices, including one for early-stage breast cancer, which can also be found at BresDex (breast cancer decision explorer), a website that sets out the choices between lumpectomy with radiotherapy, and mastectomy. The option grids are now part of an international collaboration, including with the Dartmouth Center for Health Care Delivery Science in the US, says Edwards. But such decision aids now abound – the UK NHS, for example, now has at least 25 online aids as part of its shared decision making programme, including tools for localised prostate cancer and bladder cancer.

Oncologists are also beginning to use their own prediction tools in discussion with patients, but it can be difficult to present the information in a way patients can readily make sense of. The Adjuvant Online! tool to help decision making in breast cancer has been shown to result in lower uptake of drugs (see Cancer World September-October 2013), but a study has shown that patients would understand it better if pictograms were used rather than bar charts.

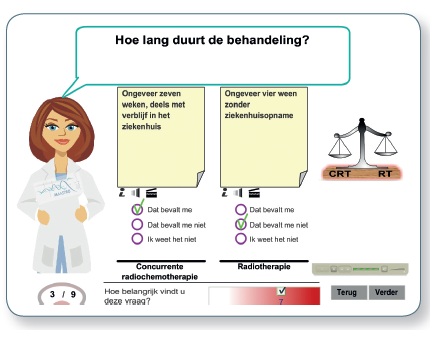

The Maastro clinic in the Netherlands has developed an information tool for patients with lung cancer (treatment-choice.info) that is separate from the prediction model they developed for oncologists, but as radiation oncologist Philippe Lambin, who is leading this work notes, so far they have not been able to integrate the two. “That’s complicated,” he says, “We tried to do it but our first attempt was a total failure, not least because patients vary enormously – some can barely read.”

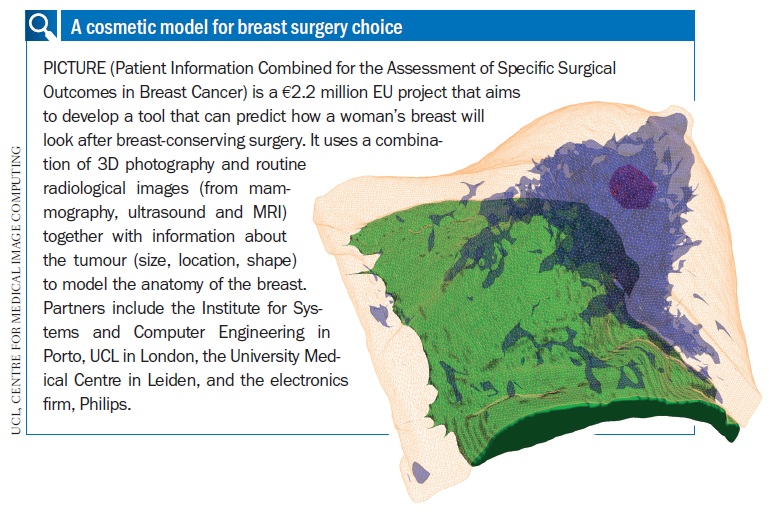

Surgeons too are doing their bit to develop tools that can help patients make informed decisions, for example imaging software that shows how a woman’s breast will look after breast-conserving surgery. The tool models simulations of cosmetic outcomes according to what is possible for a woman’s breast, given what needs to be removed (see below). Maria João Cardoso, head breast surgeon at the Champalimaud Foundation in Lisbon, who is involved in this project, says this puts women in a better position to make an informed choice, and their preferences can then be fed into multidisciplinary team meetings so the right decisions are made about margins and other factors. If none of the conserving options are good, the woman may opt for mastectomy, she says.

Surgeons too are doing their bit to develop tools that can help patients make informed decisions, for example imaging software that shows how a woman’s breast will look after breast-conserving surgery. The tool models simulations of cosmetic outcomes according to what is possible for a woman’s breast, given what needs to be removed (see below). Maria João Cardoso, head breast surgeon at the Champalimaud Foundation in Lisbon, who is involved in this project, says this puts women in a better position to make an informed choice, and their preferences can then be fed into multidisciplinary team meetings so the right decisions are made about margins and other factors. If none of the conserving options are good, the woman may opt for mastectomy, she says.

In the US, several medical and cancer centres have set up dedicated decision units to support patients. Dartmouth was among the first, while the decision services department at the breast care centre at the University of California, San Francisco, has become particularly well known because of the work of Jeff Belkora, who has been prolific in discussing the ‘secrets’ of putting shared decision making into practice. Decision aids play a part, but Belkora’s team majors on helping patients prepare for consultations – or the typical ‘visit cycle’ with various cancer specialists as he puts it – by viewing videos, making notes, drawing up questions and recording the visits as audio files. Key to this is deploying a team of pre-medical trainees who help patients prepare in this way, and oncologists report that they are able to start discussions at a higher level of explanation.

In the US, several medical and cancer centres have set up dedicated decision units to support patients. Dartmouth was among the first, while the decision services department at the breast care centre at the University of California, San Francisco, has become particularly well known because of the work of Jeff Belkora, who has been prolific in discussing the ‘secrets’ of putting shared decision making into practice. Decision aids play a part, but Belkora’s team majors on helping patients prepare for consultations – or the typical ‘visit cycle’ with various cancer specialists as he puts it – by viewing videos, making notes, drawing up questions and recording the visits as audio files. Key to this is deploying a team of pre-medical trainees who help patients prepare in this way, and oncologists report that they are able to start discussions at a higher level of explanation.

It is a clever use of scarce resources – people in the shape of pre-meds – and Belkora reckons that other centres could do the same, if not with medical trainees, then with other trainee professionals on rotation in nursing, mental health and social work. “They can help patients prepare for two hours so a 30 minute visit with an oncologist goes as productively as possible,” he says. In the UK, the NHS SDM programme is training nurses with at least ten years’ experience to offer telephone support to patients who use online decision tools.

Epstein’s team at the University of Rochester runs educational programmes for oncologists in communications. He talks about the need for doctors to understand their own role as only part of the process by which patients construct their preferences, alongside other influences such as family and the media, all of which might affect a patient’s expression of their own values, especially in the very unsettling context of cancer. “It is important to be ‘in tune’ with their patients and foster a ‘shared mind’ where new ideas and perspectives emerge among two people.” Often, oncologists have had little training in communication and can feel overwhelmed, especially when talking to patients about bad news and treatment choices, says Epstein. “Some do feel they are doing a good job, but when we have sent in ‘sleuth’ patients as part of a study we are doing, it is often the case that they are not asking patients what their goals are, and they assume patients understand the information they have been given.”

“Some feel they are doing a good job, but often they are not asking patients what their goals are”

Patients, he says, often leave a visit with misunderstandings about prognosis. They may understand terms such as ‘response rate’ as ‘cure’. Several studies show that up to 40% of patients with stage 4 solid cancers believe cure is somewhat likely, whereas the overwhelming majority of their oncologists said not. “This can have major implications for treatments and what people choose to do with their lives,” he says.

Oncologists, he adds, really do need to learn ways to check that patients have understood and are on the same wavelength. These skills cannot be learnt from reading books. “We carry out communication training in oncologists’ offices – it’s remarkable what you can accomplish in a couple of one-hour sessions and they love it because they don’t have to travel and perform in front of their peers. Calculating chemotherapy doses is much easier for them – this is the hard stuff.”

Epstein supports the use of decision aids. “We need all the tools we can get for patients and their families,” he says, and adds that doctors must respect decisions made by adults that could be seen as unreasonable, as long as they are not operating out of fear or mistaken beliefs. For example, in the US, many patients believe that surgery actually spreads cancer, and can be influenced by persuasive advertisements for alternative medicines.”

A case study he gives highlights how important it is to empower people to make their own decisions. It concerns a geriatrician in hospital with terminal colorectal cancer and with various conditions such as a massive ulcer and a biliary tract infection. “He was struggling with the decision about whether to leave the hospital and die at home or try one more procedure. I spoke with him and his family and the hospital team about the options, and he said he knew it was his choice. But he said that he was too overwhelmed to think clearly.

“I asked him if he would like a recommendation – it was his decision to accept my offer or not – and he said yes. He seemed to be relieved to be unburdened from the obligation to make a choice for which he was overwhelmed. He was comfortable making a decision, following the recommendation, to go home and spend time with his family, despite the preference of some of his family members that he ‘fight’.”

A key point, concludes Epstein, is that decision making should be guided by compassion, quality of life and patient autonomy. Balancing the three involves ‘muddling through’ and a patient-centred approach to communication where patient preferences are sought, informed and enacted in difficult, complex situations in which clinical evidence alone is insufficient to guide decisions.