Scientist or artist? Michael Peckham, who is best known for his contribution to the treatment of testicular cancer and Hodgkin lymphoma, and was involved in founding the European School of Oncology, refuses to choose and has always been both. Painting and medicine have complemented one another throughout his career, as he explains.

When I decided to become a doctor, art and science were regarded as separate entities. I was already immersed in the arts and in the first years after qualifying I had doubts about continuing with medicine, not helped by having to spend two years in the army in the last batch of conscripts before military service ended. Paradoxically, being removed from the conventional career ladder was liberating. I was on my own as a medical officer to an infantry battalion and I had time to think about what I wanted to do in medicine and art. I made no distinction between a scientific and an artistic mind and I thought that the separation of artist and doctor was artificial.

My first job at University College Hospital was in surgery and radiotherapy – then the only dedicated cancer specialty. Influenced by Gwen Hilton, the gentle and cultured head of department, I decided to specialise in oncology. My art was first shown in 1960 and I had my first solo exhibition in 1964. The paintings were abstract landscapes in oil on canvas and I was reviewed as a colourist. Around this time, I bought a book on cell proliferation and discovered how to label cells with radioactive thymidine and coat the slides with photographic film. When the film was developed, cells synthesising DNA had black grains of silver over their nuclei. Witnessing the dynamics of dividing cells was a eureka moment for me both as artist and doctor.

Subsequently, I spent two years in Paris on a Medical Research Council Fellowship working on leukaemia and lymphoma at the Institut Gustave Roussy. This was an exciting period in art, medicine, and politics – just before the student riots of 1968. Bone marrow transplantation had been used in acute leukaemia, there were high hopes for immunotherapy, and radiation techniques had been evolved to cure Hodgkin’s disease. I met Stanley Hayter, painter and print-maker, and he invited me to Atelier 17, his renowned print studio. I felt a pull between ‘laboratories’ in two worlds: Hayter’s in Montparnasse and the cell biology laboratory a few kilometres away in Villejuif. Paris was a turning point. Science added a new dimension to my clinical work and gave fresh impetus to my art.

My paintings in the 1970s often incorporated a circle image that I thought came from diagrams of the cell division cycle, although there were other possible origins. Earlier, I had made a construction using the circular red lens of a road lamp and a cycle collage – bought by Eugene Rosenberg, the architect who designed St Thomas’ Hospital – that had the title Pit Head after the colliery pit head wheels I knew from my youth. Later, I incorporated figures into three-dimensional collages behind a frontage rather like a stage set. One construction, The door, came from a poem by Miroslav Holub, doctor, immunologist, and poet, whom I had met at a haematology workshop in Prague and a poetry festival in London. In The Root of the Matter, he wrote lines that resonated with my concept of art: “There is poetry in everything. That/is the biggest argument/against poetry.”

“Many of the images I used came from my experience as an oncologist”

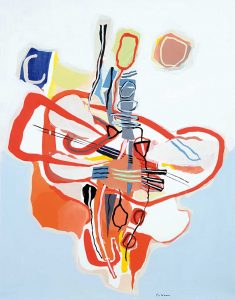

In 1973, I was appointed to a chair at the Royal Marsden Hospital and Institute of Cancer Research. Curative treatments for Hodgkin’s disease, lymphoma, and testicular cancer were becoming a reality and my unit at Sutton was at the forefront of these advances. This was an intensely active period and I remember drafting the first paper on our use of carboplatin in Zurich airport on my way back from a lymphoma conference in Lugano. On the wards, we had seen young men dying from rapidly progressive cancer. When effective treatments were developed, the change was dramatic, and it was obvious that a transformation was underway. The human figure became more prominent in my paintings and I used colour more freely, perhaps reflecting our elation at what was being achieved on the wards.

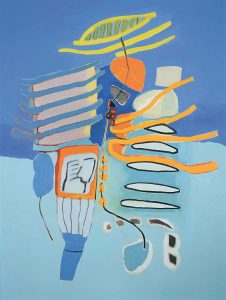

I made small pen drawings routinely in the notes of patients on which I marked the extent of tumour. The different visual patterns led to a staging system that helped us choose the best form of treatment. Over time, these drawings made with practical intent seemed powerfully symbolic: the figures had an imagined content related to patterns of disease scribbled into the notes on busy ward rounds. Thrity-five drawings were shown at the Royal Academy in 2004 under the title Treatments. An exhibition of my collages and paintings in 2017, Balance of the Interior, explored the human form as a zone of concealment and mappable space, notions that had their origin in the small images drawn in my clinical notes. A couple of years earlier, I had painted my own experience of the pain of post-herpetic neuralgia (Zona). In these paintings, the cadmium pigments that I habitually used gave way to a sombre palette of muted greys.

Many of the images I used came from my experience as an oncologist. When I looked at a person I saw the external form of a body, but I also sensed the disposition of structures under the skin and imagined cellular images and processes. Seeing past the skin became a reality with the discovery of X-rays. It caught the imagination of artists in the early 20th century and chimed with Paul Cezanne’s efforts to define an order underlying the surface of nature, as well as Alberto Giacometti’s efforts to get to the essence of a head much as a physicist pursues subatomic particles. I was familiar with the human figure rendered translucent by scanning in the search for a tumour, and had a preoccupation with hidden forms linked with other strands of interest. For example, the images in my exhibition, Philomena, in 2013, derived from notions of concealment, detection, and metamorphosis.

In a valedictory lecture at The Hague, I compared ‘seeing’ in the context of a medical advance and a new departure in painting. The discovery of platinum drugs that transformed the curability of testicular cancer came serendipitously from an astute observation of the unexpected: a product interfering with bacterial growth diffusing out from platinum electrodes assumed to be chemically inert. One source of Piet Mondrian’s paintings came from the way he saw fragments of sky between the branches of trees and used this to create the delineated geometric blocks of his mature paintings. Looking at the emergence of new developments in art and medicine is intriguing, although comparisons of their respective quality and importance are generally unhelpful. As John Berger asked in A Fortunate Man: the Story of a Country Doctor: “How does making a correct but extremely difficult diagnosis compare with painting a great canvas,” and concluded that “the comparative method was absurd”.

I like the idea of cumulative effort: the build-up over time that can’t be replicated later when there is time and I have accumulated many small works that touch on most aspects of my experience. The painter Patrick Hayman once told me to keep my sketches as I would feed on them later. Many drawings are of the commonplace: a hospital tap, the level crossing gate I went through on my way to the hospital, a datapoint on a graph. The importance of a subject lies in its interpretation: Giorgi Morandi’s bottles, Claude Monet’s water lilies, and Philip Guston’s boots were transformed in different ways into memorable images. My current paintings are concerned with human presence: places people have inhabited or passed through and the signs that indicate that they have been there. Although not explicit, the theme connects with notions of concealment and revelation and with issues of mortality and continuity that are of concern to both artist and physician.

Reprinted from The Lancet, 391 (10120), Michael Peckham, Art and oncology: one life, pp530-531. © 2018, with permission from Elsevier.

Images courtesy of Michael Peckham