After more than ten years developing and piloting a collaborative approach to evaluating new medical technologies, EUnetHTA will come to an end in 2020. The Commission is proposing a replacement with mandatory powers, but are Europe’s governments prepared to sign up to it? Peter McIntyre reports on the battle lines and the debate.

The European Union is in a race against time to strengthen cross-country collaboration in assessing the therapeutic value of new drugs and introduce an effective Europe-wide system of health technology assessment (HTA).

The need for change has been fuelled by dramatic increases in the price of drugs, and by very low use by member states of a system for voluntary collaborative clinical assessments when deciding which drugs to purchase or reimburse and at what price.

The result is fragmented assessments across different countries, delays in new medicines reaching patients, and a lack of transparency about the therapeutic value of expensive new therapies.

In January 2018, the European Commission proposed a new regulation to make it mandatory for all states to make use of the joint EU reports, rather than continue repeating work to different standards and sometimes reaching different conclusions.

However the European Council – the combined voice of EU Health Ministers – is opposing any compulsory element that might restrict the rights of member states to decide on which drugs and innovations to reimburse.

Delayed access: the size of the problem

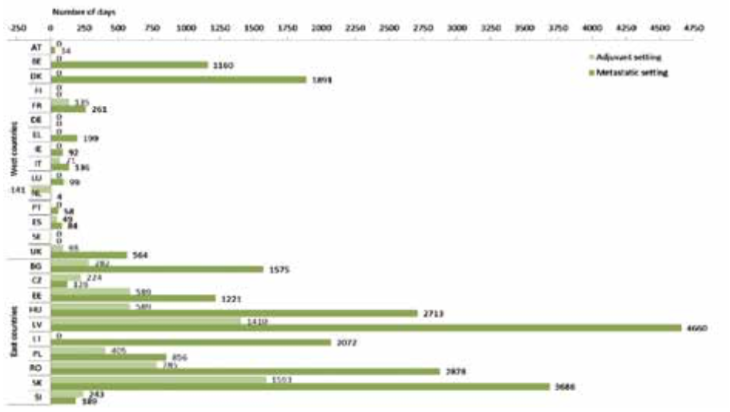

Under the centralised approval process, marketing approval for new cancer drugs is decided by the European Medicines Agency and becomes effective on the same date across Europe. But it is up to governments, health authorities and social insurances to decide whether to reimburse the treatment and to negotiate on price. The time taken to complete this exercise can vary hugely across Europe. The example presented in the figure above shows the variations in the time from approval to access for the drug Herceptin. EUnetHTA was set up in 2009, as a collaborative health technology assessment network, to try to minimise these delays, but the voluntary nature of the network limited its effectiveness, and it is due to come to an end in 2020.

While some drugs may offer marginal benefit, others, such as immunotherapies for patients with advanced melanoma, can add years of life to patients who respond. In an article published in June 2017 in the Swedish doctors’ journal, two cancer pathologists estimated that the decision in some regions to delay access to ipilimumab, the first cancer immunotherapy drug, led to an estimated loss of at least 840 years of life (Läkartidningen 2017, 114:EL7S).

Source: F Ades et al. (2014) An exploratory analysis of the factors leading to delays in cancer drug reimbursement in the European Union: the trastuzumab case. Eur J Cancer 50:3089‒97 republished with permission from Elsevier

The European Cancer Patient Coalition and European Cancer Leagues support the proposal, arguing that mandatory co-operation would improve patient access to high-value treatments (see below).

Industry is also in favour, on the grounds that a mandatory Europe-wide system will simplify their task of providing clinical data, and should speed access to their products. A consortium of pharmaceutical industry bodies, including the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations, welcomed the proposal as “a unique opportunity for greater alignment on clinical evidence generation requirements, ensuring consistency, transparency and synergies in clinical assessments by member states.” They argue that, “In a purely voluntary framework joint clinical assessment reports are not sufficiently used at the member state level.”

The European Parliament will not agree its position until the autumn. However, the proposal has been discussed by the influential European Parliament Committee on Environment, Public Health and Food Safety (ENVI). Spanish MEP Soledad Cabezón Ruiz, the ENVI rapporteur, says the proposed regulation represents “a high degree of added value for the EU”. She welcomes it as “a further step towards closer EU integration, in an area as important as health”, and says it will help address pressing issues around patient access to medicines and health system sustainability.

“In the last decade, the price of anti-cancer drugs has increased by up to 10 times more than their effectiveness as treatments. A number of recent studies on cancer drug authorisations have pointed out that, on the basis of an average of five years’ monitoring, only 14–15% of the drugs improve survival rates,” says the ENVI rapporteur.

Patient groups welcome the Commission proposal

There is widespread support amongst patient groups and industry for stronger HTA assessments with no opt-outs.

The European Cancer Patient Coalition (ECPC) says that mandatory use of joint assessments is the only way to get the best available cancer therapies to all European patients without unnecessary delays. Lydia Makaroff, ECPC Director, said: “What we are seeing with EUnetHTA is really fantastic joint assessments being produced, but the uptake in countries remains low for a variety of reasons. It is very hard for industry to get on board. We can see that they put resources into producing and contributing to this joint assessment and the countries ignore it… There is a single market within the EU and the European Union has a mandate to improve harmonisation.”

The Association of European Cancer Leagues (ECL) says that mandatory co-operation would improve patient access to high-value treatments and help payers to make wise decisions on pricing and reimbursement.

Both umbrella organisations say that the patient experience has to be central to the assessment of new drugs. Lydia Makaroff said: “Patients are the only people who can talk about the actual experience of taking therapies and deciding between different therapies. Without patient organisation involvement we are missing these unique insights and experiences.”

EURORDIS (Rare Diseases Europe) says that mandatory use of high-quality HTA is essential to give rapid access to new drugs to patients with rare diseases, who often have few treatment options. It will also highlight countries that fail to allocate sufficient resources to healthcare.

“Currently, the situation authorises member states to cherry-pick which data they want to consider, which methods they want to use, depending on which decision they want to make,” says EURORDIS Access Director, François Houÿez. He points out that European countries are failing to make decisions on reimbursement within 180 days as required by the EU, and argues that centralised assessments starting earlier in the process would speed up decisions by four to seven months.

“Citizens will have the joint report with all the evidence, so member states will have to tell the truth. Where health is not a priority they will have to be clear with their citizens. It is not because the drugs are not working, it is because they have decided to allocate resources to other budgets.”

European governments are less enthusiastic. Some smaller countries that lack the expertise and resources to carry out their own evaluations, back the proposal. But when it was put before a meeting of the European Council Health Ministers in June 2018, there was extensive opposition to any compulsory element that could restrict the rights of member states to decide which drugs and new health products to reimburse (see next box).

Kiril Ananiev, the Bulgarian Minister of Health who chaired the meeting, concluded that only three member states, representing 5% of the European population, completely backed a mandatory system, whereas nine countries, representing more than 70% of the European population, opposed it or had strong reservations.

The clock is now ticking on the Commission’s proposal. Agreement on any new regulation requires accord between the European Commission, Council and Parliament. If there is not at least an outline agreement by the end of the year, the whole process could be shelved, because European Parliamentary elections are due in May 2019, prior to which there are two to three months ‘white time’ when controversial issues are dropped.

That means time is running out to convince governments to find a way forward that would address the unacceptable waits many patients face in accessing high-value medicines.

What’s behind the proposal?

The European Union has been supporting health technology assessment in one form or another since 2004, when the European Commission and the Council of Ministers targeted HTA as a political priority. Since 2009 it has backed the EUnetHTA network, a voluntary collaboration between European HTA organisations, as a way to bring “added value to healthcare systems at the European, national and regional level”. But the Commission has now concluded that this voluntary, project-based system cannot keep pace with the speed of developments and is not being taken seriously by the member states.

The European Commissioner for Health and Food Safety, Vytenis Andriukaitis, argues that project-based co-operation has significant limitations, which resulted in a relatively low number of joint outputs and low uptake of joint work in national health systems.

According to the European Commission, the EUnetHTA initiative has not prevented fragmentation of the internal market or duplication of assessments. There is clear irritation that high-quality work put in by EUnetHTA has not produced stronger results. Only five reports have been produced over the past two years (more are in the pipeline), and only a few countries have fully acted on their findings (see box). As one official put it: “Once you do it together, you need some kind of commitment that you will use it in your national process. Otherwise what is the point?”

Under the proposed Regulation on Health Technology Assessment, a new ‘Coordination Group’ would be set up to report on new medicines and medical devices, using common HTA tools, methodologies and procedures. It would be responsible for joint clinical assessments, focusing on: innovative health technologies with potential impact for patients; scientific consultations with developers; and identifying promising health technologies.

In contrast to the current voluntary EUnetHTA set up, which involves a collection of HTA bodies and academic institutions, the Coordination Group would comprise official representatives from each member state. The European Commission would provide scientific, secretarial and IT support and host expert meetings.

Member states would continue to make decisions on which medicines to buy or reimburse in their own health systems. But significantly, they would have to start their assessment using the joint EU report, and make reference to it when explaining their decisions. They could only produce their own HTA reports under exceptional circumstances – for example if their population profile differs significantly from the European average.

The Commission claims that their proposal will save up to € 2.65 million a year, as countries will not need to duplicate work. However, the Commission also expects the new system to cost € 7 million a year in running costs, on top of a € 9 million contribution to the work on joint outputs. The sums are complicated, as the current EUnetHTA already costs € 5 million a year, but the new system does not look like a saving at a European level – and not at national level either if the member states insist on carrying out their own assessments.

Does voluntary joint assessment work? The EUnetHTA experience

The main existing EU effort in health technology assessment (HTA)is to support project-based collaborative assessments conducted by EUnetHTA, a network of government appointed organisations, regional agencies and non-profit organisations from EU Member States, plus EEA and EFTA countries.

Over the past 12 months EUnetHTA has published three final relative-efficacy assessments on drug treatments, all of them on cancer treatments: alectinib as monotherapy first-line treatment for ALK-positive advanced non-small-cell lung cancer; regorafenib for treatment of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) after treatment with sorafenib; and midostaurin in combination with consolidation chemotherapy for patients with acute myeloid leukaemia (AML).

A number of non-drug innovations were assessed in 2018, including high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) ablation for the treatment of prostate cancer and the added value of gene-expression signature for adjuvant chemotherapy decisions in early breast cancer.

A study on how reports have been used by countries in making decisions, and reasons for use or non-use ‒ the main issue that prompted the Commission to propose the new Regulation ‒ is being conducted by the UK’s NICE at the request of EUnetHTA.

Niklas Hedberg, newly appointed chair of the EUnetHTA Executive Board, says that it will be his priority for the final two years of the project to get more countries to make use of their findings. “We must make sure that products that come out are relevant and can be implemented in as many settings as possible, to come to actual use. Whether or not it must be mandatory or stay voluntary has become a political issue, and I don’t think it is for EUnetHTA to be vocal about. But it should not be controversial to implement conclusions that are valid for a lot of markets in most countries.”

Although EUnetHTA has not taken a position on the European Commission’s proposal, it is anxious that something is in place when their mandate comes to an end. Deadlock would be “potentially dramatic” says Hedberg. “The project comes to an end in late May 2020 and we must support measures to continue this co-operation and its work. We must try to see how we as a network can prepare for that. I don’t have those answers yet.”

The debate

The European Council agrees that a better system is needed, but larger countries with their own robust HTA systems strongly oppose compulsory elements. Germany and France have promised to present counter proposals.

Jens Spahn, the German Federal Minister for Health, told the June Council meeting: “Germany rejects the mandatory nature of this particular instrument… they interfere with sovereignty of member states when it comes to healthcare systems in the member states.

“We are going to be pooling our expertise with others at EU level, but one thing that we would not be prepared to do would be to take on board, ‘lock, stock and barrel’, European level assessments. We need to be able to tailor things to our own system’s needs and characteristics.”

Agnès Buzyn, French Minister for Solidarity and Health, said clinical assessments cannot easily be detached from procedures guiding price setting and reimbursement. Compulsory use of joint clinical assessment reports and non-duplication were critical points. “We cannot accept them.”

The UK will not be part of any compulsory system after Brexit, but nevertheless spoke against the proposal. James O’Shaughnessy said that, while NICE works closely with other HTA bodies in Europe, the UK had fundamental objections. “It is essential for clinical assessments to be flexible enough to accommodate national perspectives, as each member state will have different systems and practices.”

The UK will not be part of any compulsory system after Brexit, but nevertheless spoke against the proposal. James O’Shaughnessy said that, while NICE works closely with other HTA bodies in Europe, the UK had fundamental objections. “It is essential for clinical assessments to be flexible enough to accommodate national perspectives, as each member state will have different systems and practices.”

Even countries sympathetic to strengthening the current system expressed concern. Finland warned that European joint assessments might be done at too early a stage, with insufficient data. “This can lead to a situation where new expensive medicines can be taken into wide use with very little knowledge about them.”

A few Health Ministers spoke strongly in support of the European Commission proposal. The Greek Health Minister Andreas Xantho said that different national assessments of the clinical value of new drugs distorted the European market and led to health inequalities. “Such a co-operation will guarantee results of high quality; it will reinforce transparency and commitment from the industry, and will constitute an important tool for each member state to be able to decide [in a timely way], in the context of its competencies, the cost of any treatment.”

Romania too supported the compulsory principle, pointing out that none of the joint assessments undertaken by EUnetHTA had been properly implemented “even in the systems of those member states that were directly involved in the assessments”.

Maggie De Block, Belgian Minister for Social Affairs and Public Health, expressed irritation at what she saw as foot-dragging by the European Council. Voluntary co-operation had shown its limitations, and something more structured was needed to achieve high-quality HTA to win the trust of their citizens. “It is always difficult to understand that in one member state a product is scientifically grounded and therapeutically available, but not in a different member state. Civil society, patient organisations, professional bodies, representatives of industry, they are sending out clear signals that we have to get off the starting blocks and do some intensive work.”

The Netherlands is one of the leaders of HTA in Europe, coordinating EUnetHTA, and active in regional co-operation. Minister for Medical Care Bruno Bruins accepted that the EU needs a mechanism that leads to a broader participation and uptake by member states. However, he voiced concerns about the role of pharmaceutical companies in HTA. “Important changes and improvements need to be made before we could agree with the regulation for a more structural approach, whether obligatory or voluntary.”

There is a mood amongst many countries to help the current Austrian presidency to bring the Council and the Commission closer. The European Commissioner, Vytenis Andriukaitis, also accepts the need for compromise, telling the Council they could achieve their objectives while fully respecting national competencies. But he said that health inequalities needed to be addressed. “Everyone has the right to actively access affordable treatment. Patients are in the middle – no matter where those patients are.”

How health ministers divided on the European Commission proposal

Member states at the European Council meeting in June 2018 tended to divide according to the size and the effectiveness of their current HTA systems:

Austria: Assessment of innovation will become ever more important and strengthening co-operation will increase efficiency and be good for patients. But use of HTA has to be in line with national needs. Has a reservation in principle for proposals that restrict national freedom to act.

Croatia: The Commission’s proposal does not affect the rights and obligations of member states. The voluntary model has limitations and a positive debate is needed to ensure HTA continuation after 2020.

Cyprus: Supports the Commission’s proposal. Voluntary co-operation has serious limitations because of lack of will of important elements in the pharma industry to participate.

Czech Republic: States should have the right to add to HTA assessments without notifying the European Commission or asking permission, as each country has its own national comparator and patient population. The EUnetHTA system is not perfect, but this does not mean adopting a mandatory system. “Lack of access to the market is not linked to the differences in national procedures and in HTA methodology… What often limits the access of patients to innovative health technology are rather the high prices demanded by the industry.”

Denmark: Each health system is unique and there is a high degree of diversity which makes it unreasonable to impose a mandatory system. Where some countries might use a particular pharmaceutical, others might use surgery. “Mandatory uptake is not the right path.”

Estonia: Supports the aim of the proposals and the mandatory uptake of joint clinical assessment, provided timeliness and quality is maintained. More flexibility is needed to allow countries to do additional assessments on national issues not reflected in the joint report.

Hungary: Proposal should be seen as a basis for negotiating something with more flexibility.

Ireland: Variations between countries means agreeing costs and reimbursement should remain the role of member states. But the proposal provides a basis for progress.

Italy: Strong believers in the HTA system but share many of the concerns about compulsion. Europe needs a stronger way to promote voluntary co-operation.

Latvia: Favours the Commission’s proposal to maximise the use of limited financial resources and capacity. Wants a better balance between mandatory and voluntary elements.

Lithuania: Wants a coherent durable and sustainable co-operation system that is more comprehensive and of higher quality. The regulation should strike a balance between obligatory and optional elements.

Luxembourg: Welcomes the proposal – but notes there are alternatives between the status quo and the obligatory use of reports.

Malta: After two decades of co-operation the time is right for a permanent framework and this is a good basis for a system that stimulates knowledge, promotes information sharing and makes better use of limited competences – an advantage for small states with very limited resources. Mandatory uptake requires a more flexible approach.

Poland: Joint reports should be recognised in national decision-making processes, but should not restrict further national assessment based on specific data and needs. Mandatory use of assessments remains a major concern. Concerned also that giving pharma access to the process will put member states under pressure when taking reimbursement decisions. Find a constructive voluntary solution.

Portugal: Views the proposal positively and believes the council should hold constructive discussions with the European Parliament. Not right just to focus on the issue of compulsion.

Slovakia: Voluntary co-operation has failed to facilitate the development of HTA in Slovakia, which supports and welcomes the commission proposal as a tool to trigger its development.

Slovenia: European Council discussions have not got very far. The door is open for an in-depth proposal.

Spain: The current proposals would have a negative impact. Devise a model which guarantees that member states are the only ones responsible for the organisation of their health systems.

Sweden: Sweden has 21 county councils that each make their own decision for hospital drugs. Member states need flexibility to adapt assessments to the national context. The quality and timeliness of reports is of utmost importance.

The views of Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, the Netherlands, Romania and the UK are covered in the main article.

Could cross-country groups offer a bridge?

Rising pressure on access and sustainability has already prompted many countries to band together to share information and boost their bargaining power.

BeNeLuxAI

One such grouping, comprising Belgium, Netherlands, Luxembourg, Austria and the Republic of Ireland, goes by the name of BeNeLuxAI. The idea is to share technology assessments, exchange information on medicine policies, scan which expensive innovations are about to hit the market and – significantly – make it easier to negotiate medicine prices, demanding greater transparency from industry on costs build-up of pharmaceutical products. On signing up to the alliance in June 2018, Irish Health Minister Simon Harris said he wanted the innovative medicines to be available “at a price that is affordable and sustainable in the context of the ever-competing demands for resources right across our health service”.Valletta Declaration group

Cyprus, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Malta, Portugal, Romania, Spain and Slovenia, and most recently Croatia, with a combined population of 160 million people – 32% of the EU population – have joined together to form the Valletta Declaration group. Its aim is “to collaborate to improve patients’ access to new and innovative medicines and therapies and to support the sustainability of their national health systems”. The group held its fourth meeting in Lisbon in

May 2018, but the work is at a very early stage, with an agenda that continues to look for candidates for joint assessment and negotiation, and “explore new areas of activity” and “analyse therapeutic areas of growing expenditure”.Central European Group

Poland, Hungary, Slovakia, Lithuania and the Czech Republic have formed a Central European group. This is led by Poland, which established its own Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Tariff System (AOTMiT) in 2005, and overhauled its guidelines in 2016.Aneta Lipińska, Acting Head of Analysis and Strategy at AOTMiT, says the guidelines lead to better evidence and more accurate analysis, leading to informed decision making and “the greater likelihood of successfully meeting the real health needs of citizens”. According to a 2017 paper in the Journal of Market Access and Health Policy, the new guidelines are as clear and detailed as those used by the UK’s NICE. AOTMiT carries out 70‒80 analyses each year of dossiers submitted by market authorisation holders, and assessments for the Ministry on off-label use and other issues.

A bridge

These regional initiatives are done on limited budgets and are not financially supported by the EU, but they do make use of EUnetHTA methodology and tools.Niklas Hedberg, newly appointed chair of the EUnetHTA Executive Board, said they could be a link towards a new system if there is a gap after EUnetHTA ends in 2020. “I am very hopeful we will find alignment between EUnetHTA and the regional initiatives in the next two years. I definitely have an expectation that someone will provide a bridge between EUnetHTA and the new system, because everything we have learned in EUnetHTA will be at risk if there is no bridge or transfer provided.”