Getting cancer as a teenager or young adult can severely disrupt an important period of emotional, physical and social transition. Tailoring services to fit the particular needs of this age group can make a huge difference.

Various terms, including adolescents, youth, teenagers, young adults and young people, are all used to describe people who are neither children nor adults. In the UK, we talk about teenage and young adult (TYA) cancer care, but adolescent and young adult (AYA) care is used in Europe, the US and Australasia. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines young people as those between the ages of 10 and 24, adolescents as those between 10 and 19, and youth between 15 and 24, so the entire range is from 10 to 24 years of age. However, for the purposes of this article, we will focus on young people between the ages of 13 and 24.

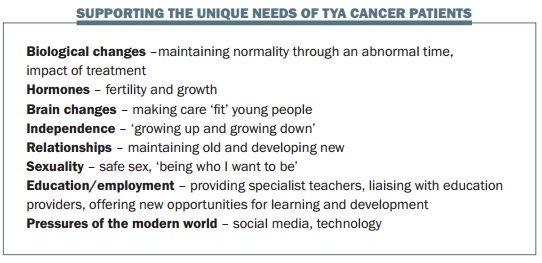

Adolescence is a time of great change, challenge and culture. Young people undergo huge biological change, physically growing up and getting bigger. Going through puberty means significant hormonal changes, and there are also major changes in the brain during this period. Adolescence is also a period of gaining independence, moving away from parents and becoming independent of them in many ways, including emotionally and financially. Relationships formed during adolescence are important, with peers and friends becoming very significant. Adolescence is also a period where sexuality is determined, and this can be a difficult time for some young people.

Most adolescents have to make important decisions about their education and careers. They also face other challenges, such as getting a driving licence. Changes going on in the world, including technology and social media, give greater freedom to young people, but also add pressure.

Question: It is increasingly recognised that there are specific and special needs to consider in young people aged 13 to 24 who get cancer. But supportive care needs are poorly characterised for young adults aged 25 to 40, and their specific needs are left under-researched. Are there any signs of developments for these young adults who face specific challenges, some of which are similar to the younger group but which may also include having marital and family issues, young children, interrupting careers and financial problems?

Answer: I agree with the point raised, but current UK guidance is for people up to 24. However, age-specific challenges clearly continue above this age group. I’m not aware of any changes in UK policies that will extend the upper age limit, but in reality I’m finding that we have the opportunity to raise awareness of the special needs of this age group, and other people are starting to think about the transferable nature of some of the challenges that we have addressed in TYA cancer care.

TYA cancer statistics

The 15- to 24-year-old age group accounts for only 1% of all new cancer registrations in the UK (all cancers apart from non-melanoma skin cancers), with slightly more males than females. The incidence of cancer in young people rose dramatically throughout the EU in the 1990s. In the last decade it stabilised among males; among females, however, the incidence continued to increase, by about 10%.

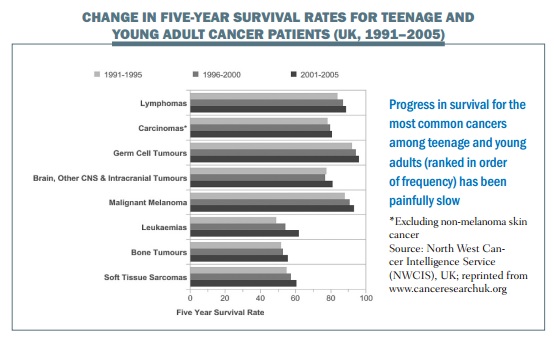

The main types of cancer in teenagers and young adults in the UK are lymphomas, carcinomas, germ cell tumours, brain and CNS tumours, malignant melanomas, leukaemias, bone tumours and soft tissue sarcomas.

Some research has been done to look at the causes of these types of cancer in this age group, some of which are paediatric cancers and others adult types. Malignant melanomas are known to be associated with UV exposure, and cervical cancer, which accounts for some of the carcinomas, has a known association with the human papillomavirus. In addition, growth and hormonal factors during puberty may trigger cancers in this age group, and genetic syndromes are implicated in some cancers. Unfortunately, we are also seeing more secondary cancers due to cancer treatment during childhood.

Some research has been done to look at the causes of these types of cancer in this age group, some of which are paediatric cancers and others adult types. Malignant melanomas are known to be associated with UV exposure, and cervical cancer, which accounts for some of the carcinomas, has a known association with the human papillomavirus. In addition, growth and hormonal factors during puberty may trigger cancers in this age group, and genetic syndromes are implicated in some cancers. Unfortunately, we are also seeing more secondary cancers due to cancer treatment during childhood.

Survival from cancer in this age group is improving. In the UK, five-year survival is now approximately 80%, with slightly higher survival in females than males. Across Europe this can range up to 92% (in Iceland). But it is important to recognise that the survival rate in the 15- to 24-year age group is significantly lower than that in children under the age of 16.

Five-year survival rates for three diagnostic periods from 1991 to 2006 in the UK are shown in the graph (left) They show a considerable variation in survival between different diagnostic groups, which has remained fairly consistent over the years. The most important thing to take from the graph is that survival for soft tissue sarcomas and bone tumours has not changed significantly, and is still poor. Unfortunately, cancer remains the leading cause of death in UK teenagers and young adults after accidental death, accounting for 310 deaths in young people each year, with brain and CNS tumours being the most common causes of cancer deaths.

Survival rates are increasing, however, which is reassuring. Death rates across Europe have decreased by around 50% since the 1970s, reflecting improvements in treatments over the last 40 to 50 years.

Clinical challenges in TYA cancer

There are several challenges in TYA cancers. Survival rates for teenagers and young adults have improved less than for adults and children, and the incidence is increasing in this age group. One reason for poorer survival is limited access to clinical trials. Paediatric trials often have a cut-off age of 16 years, while adult trials start at 18, so teenagers can miss out. In the UK, at least, researchers are being encouraged to consider including teenagers and young adults in trials they are starting.

Another challenge is that many teenagers and young adults with cancer are diagnosed late, often in accident and emergency services. This is frequently because, even if they go to their GP several times, the GP may not consider the possibility that their symptoms could be caused by cancer, and assume instead that they are due to age, stress or lifestyle. In addition, young people may be reluctant to see a doctor because they themselves doubt their symptoms relate to a serious problem.

A further challenge is the small number of teenagers and young adults in cancer centres, so they don’t form a coherent group. There may be just one or two of them on an adult ward or department, or in a children’s hospital, and staff may fail to see that they have different needs to children or adults. Guidance is also lacking for systematic referral pathways for young people, to clarify the steps in their programme of care. In addition, there are challenges in providing end-of-life care, whether in a hospice, hospital or at home; teenagers and young adults fall between child and adult services, and greater clarity is needed about who should look after these young people in the community.

Young people who have survived cancer can be faced with many survivorship issues: financial, emotional, physical and social. Their friends may have moved on and they have been left behind, their education has often been interrupted and they may face long-term consequences from their treatment. There may be questions as to who will continue to follow them up – will it be an adult team; if not, at what point will they transition to an adult team?

UK guidance on care of young people with cancer

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) issued guidance in 2005, ‘Improving Outcomes in Children and Young People with Cancer’, which provides clear standards for service delivery. The key principles are:

- Care is centred around principal treatment centres, supported by designated local hospitals.

- A TYA-specific multidisciplinary team works out of each group or treatment centre alongside cancer site-specific teams.

- There needs to be a TYA psychosocial team that provides an umbrella over services.

- Young people must have unhindered access to age-appropriate facilities and support, and should have choice about their care.

Very different models of care have developed across the UK, despite all following the same standards and guidance. There are multiple models for delivering a good service, in the UK and throughout Europe and Australasia. The challenges that we all face are the same, but are interpreted differently depending on the support available. Service evaluations for models that are well established and new models that are being introduced will help to guide the future.

Question: The Teenage Cancer Trust has had an enormous impact on TYA cancer care in the UK. Has the existence of this organisation also influenced health policies for TYAs?

Answer: The Teenage Cancer Trust and other charities have achieved a great deal in championing the needs of young adults. They have supported the building of wards and specialist units (the Teenage Cancer Trust funds 28 units), lobbied government, funded specialist staff such as clinical nurse specialists, and provided funding for activities and research to improve the care young people receive. Charities fund much of the specialist care for TYA cancer patients, which would not be provided in a stretched health service without their help.

Question: How can we support teenagers and adults in remote and rural areas who have limited local support?

Answer: I think it’s about being clever with how we interpret support, using technology and engaging young people in ways other than face-to-face working, via the telephone or social media, and signposting them to alternative ideas of support. There’s no definition of what age-appropriate care is, but for me it’s about holistic care and supporting a young person to lead a normal life within a new normal of a cancer diagnosis. We are doing some evaluation at the moment and it has shown that not every young person gets into a teenage cancer centre. There might be ways we could look at for us to go out to the patients rather than them coming in to us, which just means giving them a call so we can advocate for them and to help them navigate their way through their treatment. The teenage cancer charity Canteen in Australia has just launched a new 24/7 counselling and support service for young people via the web.

Meeting TYA cancer-specific needs

Adolescence is a period of great change, and getting a cancer diagnosis impacts on every single aspect, so it’s crucial that we see the adolescent first and then work with them with their new diagnosis of cancer.

We must remember what being an adolescent is like and be aware of all of these issues, some of which are detailed in the box above.

Any healthcare professional or voluntary service can support young people going through cancer, by thinking about the impact on their life trajectory and how we can support normal changes through an abnormal period.

This means, for instance, being aware of the biological changes that happen in puberty, and letting young women know that, if they’ve just started their periods, they may stop, or acknowledging that changes in their body might be increased or decreased.

Hormones are affected by cancer and cancer treatment in young people, and services need to make sure that the impact on fertility and growth are considered. Care and services also need to bear in mind the changes happening within the brain: behaviour, emotions, reactions and processing may not be consistent, because young people’s brains are still developing.

Care also needs to include support around issues of independence, relationships, sexuality and education/employment during this critical period of growing up. This includes recognising the importance of peer support, supporting healthy sexuality and safe sex practices, and ensuring support for education and employment, which are critical in this age range. Young people may be fighting for their independence, but when they’re feeling unwell they may just want to be looked after.

We can’t talk about young people’s services without listening to what young people want. It is important that their voices are heard. The poster overleaf shows what young people want from cancer services, including: expert staff, to be treated as young people, have the opportunity to socialise, be respected as individuals, and feel comfortable and cared for in their environment.

Question: Because the number of teenagers and young adults who have cancer is so small, maybe it is more critical to establish a special service? In our department we only have four beds for young people with cancer in a special unit for teenagers and young adults that is part of an adult ward, which offers a different approach.

Answer: I think if you have the right team of people and approach, you can provide a specialised service in any type of environment. The age-appropriate needs should not take precedence over the need for expert care for each young person’s type of cancer. As TYA professionals, we can easily visit a neurosurgical or other specialist ward to support a young person. As a TYA champion, a lot of my role is supporting non-TYA professionals to provide age-appropriate care for young people in their care.

Supporting multiprofessional working

Multiprofessional teamwork underpins good TYA cancer care. Education is very important and several organisations support this, including:

- TYAC www.tyac.org.uk (Teenage and Young Adults with Cancer) – a UK group for professionals with a useful website and educational events

- The Teenage Cancer Trust www.teenagecancertrust.org – a great support nationally and internationally in terms of developing services and sharing experiences

- ENCCA www.encca.eu (European Network for Cancer research in Children and Adolescents) and SIOPE www.siope.eu (European Society for Paediatric Oncology) – European professional and research organisations which have educational materials and are working to define and determine what TYA cancer care is

- Canteen www.canteen.org.au – an Australian charity driving TYA care

- Teen Cancer America https://teencanceramerica.org – a group founded in 2013 aiming to emulate, in some regards, what has been done in the UK

- Critical Mass http://criticalmass.org – a US group worth following on Twitter and Facebook, offering some brilliant insight into the specific needs of teenagers and young adults with cancer.

The accredited programme that we run at Coventry University, in the UK, includes an online post-graduate certificate, graduate certificate and single modules. There is also non-accredited training available as study days, online modules and short courses. SIOPE and ESMO (European Society for Medical Oncology) have e-learning materials.

Do specialist services for TYAs with cancer add value?

BRIGHTLIGHT is the first national study of young people aged 13–24 years newly diagnosed with cancer. It is currently recruiting in England, with the aim of assessing whether specialist services add value (www.brightlightstudy.com), and will follow up every newly diagnosed young person with cancer at key points in their journeys to look at their experiences up to three years from their diagnosis. It will evaluate the association between specialist treatment and TYA services in young people and the costs involved.

BRIGHTLIGHT is the first national study of young people aged 13–24 years newly diagnosed with cancer. It is currently recruiting in England, with the aim of assessing whether specialist services add value (www.brightlightstudy.com), and will follow up every newly diagnosed young person with cancer at key points in their journeys to look at their experiences up to three years from their diagnosis. It will evaluate the association between specialist treatment and TYA services in young people and the costs involved.

Summing up

The challenges of delivering age-appropriate care to teenagers and young adults with cancer include the fact that patient numbers are small and that the care they need is complex and expensive.

Young people have traditionally been treated with either children or adults, and age-appropriate units are a relatively new approach to caring for this age group.

Geography can make care delivery difficult, and we don’t always know where patients are. Young people don’t necessarily get into specialist services, and support and care is not always equitable. TYA cancer care is a new and emerging specialty that is not always recognised.

The take home message is to ‘see the young person first and the cancer second’. This is crucial, particularly because of the age and stage of life these patients are in. Young peoples’ voices are very loud and can tell a very powerful story and help lobby for change.

Small changes, such as not having an early morning routine as you would on a children’s or adult ward, can make a huge difference, and are not difficult to implement. Networking with likeminded colleagues locally, sharing experience and collaborating can be very valuable.