Patient advocates believe their input into guiding the research process is key to ensuring the right questions are investigated in the right way. Where its been successfully tried, both sides agree there is no going back.

In the summer of 2011, Alessandro Liberati, a clinical statistician and founder of the Italian Cochrane group, typed “multiple myeloma” into the search function of ClinicalTrials.gov. He was looking for evidence about the best options for managing his own cancer, which had just recurred after many years in remission. He never found it.

In the summer of 2011, Alessandro Liberati, a clinical statistician and founder of the Italian Cochrane group, typed “multiple myeloma” into the search function of ClinicalTrials.gov. He was looking for evidence about the best options for managing his own cancer, which had just recurred after many years in remission. He never found it.

Of the 1384 trials listed on the site, only 107 were phase II/III comparative studies, of which just over half had overall survival as an endpoint, and only 10 had it as a primary endpoint. Not one trial was the sort of head-to-head comparison of different drugs or strategies that he and his doctor could use to make informed decisions about the best treatment option.

For someone whose professional life had been dedicated to the cause of evidence-based medicine, it was a disappointing and frustrating result. But not for the first time in the course of his illness, Liberati used his experience to try to change things for the better.

In a letter published in The Lancet that November (vol 378, pp1777–78), only weeks before his death, he drew attention to the “mismatch between what clinical researchers do and what patients need,” and called for a new research governance strategy.

The problem, he argued, is that academic researchers who should be championing head-to-head strategic phase III studies compete instead for pharmaceutical industry funding for early-phase trials, while “pharmaceutical companies avoid research that might show that new and expensive drugs are not better than another comparator already on the market.”

He advocated redefining the research agenda in the interests of patients, using a collaborative process that would include all stakeholders and would start from an objective analysis of existing and ongoing research.

Liberati’s experience is by no means unique. Two years earlier The Lancet had run a damning analysis of avoidable waste in clinical research, which identified choosing the wrong question as a widespread problem, alongside duplication of existing evidence, poor study design, and a failure to publish all results promptly and in full.

The report, by Iain Chalmers, a founder of the Cochrane Collaboration, and Paul Glasziou, then head of the Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine, estimated that, as a result, a staggering 85% of clinical research might be failing to contribute in any way to improving knowledge about the best strategies for treatment and care.

The evidence they cite to back their claims about “the wrong question”, was drawn from a bibliographic analysis of 334 studies about the priorities of patients, clinicians and researchers for new research, and revealed some dramatic examples.

In osteoarthritis of the knee, for example, where more than 80% of randomised clinical trials were drug evaluations, only 9% of patients and clinicians saw more research on drugs as a priority; the overwhelming majority were much more interested in evidence on the value of physiotherapy and surgery.

The divergence between the priorities of researchers and those of patients and clinicians, say the authors, reflect wider behaviour patterns. The vast majority of the most frequently consulted Cochrane reviews are about non-drug forms of treatment. Yet, even leaving aside commercially funded trials, the research community is highly focused on drugs.

An analysis of the controlled trials funded by the Medical Research Council and medical research charities in the UK between 1980 and 2002 showed they were substantially more likely to be drug trials when compared with trials commissioned by the National Health Service’s own research and development programme, where clinicians – and increasingly patients – have a much greater input in setting the agenda.

Setting the agenda

Richard Morley, a specialist in patient and public involvement in research, based at the University of York, in the UK, sums up the problem. “Things that are generally researched are things that are important to pharmaceutical companies and researchers. And while that may be the right thing for them, those priorities are not necessarily shared by the people who are the most important – patients and professionals.

“I know that researchers have the interests of patients at heart, but they also have their own expertise and their own field of interest, and things they particularly want to pursue themselves.”

For some years now Morley has been involved as a facilitator for the James Lind Alliance Priority Setting Partnership – an initiative that brings researchers together with patients and carers to define the most important research questions in a given field, very much along the lines that Liberati was calling for.

Morley says that this process brings people with different expectations, wants and needs together to talk about what is important. “It’s not public and patient involvement, it’s broader than that. It’s about patients/carers and health professionals working together to find shared priorities. When I first started, someone sent me a tweet that said, ‘Welcome to the revolution.’ And it is revolutionary. It is changing the culture of research.”

Last year Morley was one of two facilitators working with a group of around 20 patient advocates, clinicians and allied health professionals to set priorities for research into the treatment and care of people with brain and spinal cord tumours. This was the first time the James Lind Alliance had help set priorities for a cancer indication. The ‘final top 10’ questions that emerged reflected patient priorities in mitigating the stress associated with the ‘ticking time bomb’ of low-grade gliomas and developing evidence about lifestyle changes they can make to improve their prognosis, in addition to specific questions to do with the benefits and harms associated with different therapeutic strategies.

Designing the trials

Involving patient advocates in the research process is nothing new, but their input has traditionally been restricted to facilitating recruitment to trials.

This continues to pose a major problem in many countries. Studies, including a 2010 Cochrane review (doi:10.1002/14651858.MR000013.pub4) have shown that less than half of all trials succeed in recruiting their target number of patients.

Advocates can play an invaluable role in challenging widespread negative assumptions that researchers simply want to use patients as “guinea pigs” to experiment on for their own ends, and in encouraging patients to look for trials that could benefit them.

Researchers frequently seek patient input in drafting informed consent forms, to make them more accessible, and patient networks can be invaluable in spreading the word about which trials are recruiting.

However, patient advocates are increasingly questioning why they should act as cheerleaders for trials that have been designed without any input from the patient community.

Bettina Ryll, founder of the Melanoma Patients Network, challenges the assumption that all trials should be recruiting in the first place, because many ask questions of scant interest to patients, or ask them in the wrong way.

“It is in patients’ interests that only the good trials are recruiting, not the pointless ones,” she says. Indeed, she argues that “if we simply focus on making better and more relevant trials,” recruitment would take care of itself Ryll was key in organising the ‘Trials we want’ meeting in Brussels last year, which brought doctors, researchers, pharmaceutical companies, regulators and health technology assessors to a conference led by melanoma patient advocates (see the ‘The melanoma trial of the future’ documentary on YouTube).

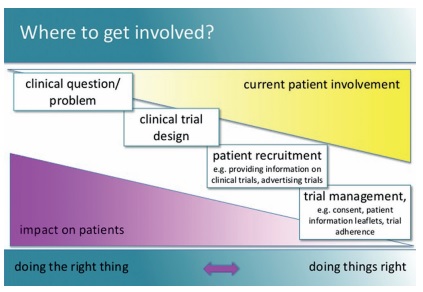

One of her slides (below) has been doing the rounds of cancer conferences, showing that the level of involvement of patient advocates is generally in inverse proportion to impact that they can have – by the time their advice is sought, all the important decisions have already been made. It calls on researchers not just to “do things right”, but to “do the right thing”.

Do the right thing

A good example of doing the right thing comes from the UK, where patient advocate involvement has been built into the structures of the UK’s National Cancer Research Institute, a strategic partnership of the main public and charitable bodies involved in cancer research.

One great advantage of the NCRI lies in its ability to promote a collaborative “portfolio” approach to setting research agendas, in place of the fragmented, competitive model that Liberati found so damaging. A commitment to train and mentor patient advocates to play a role at the heart of the process means that the patient voice is systematically heard in the identification of research questions and the development of trial proposals, often as co-applicants for research funding.

Mat Baker has been working as a patient advocate within the NCRI clinical studies group for lung cancer since shortly after his wife died of the disease five years ago. The group has responsibility for developing and managing the lung trials portfolio. Part of his role is to scrutinise trial applications, which he does from a patient perspective, ensuring they address relevant questions and are sufficiently attractive to patients to stand a good chance of achieving their recruitment goals.

“‘What would motivate someone to be part of this trial?’ is a question I often ask investigators. ‘What would engage them?’ Is it that they believe it offers an opportunity for them, or because they believe it would have the potential to improve the situation for those who come after them?

“The protocol, the purpose of the trial has to be clear and resonate and respond to the concerns of patients, either for themselves or for people who have the same conditions as themselves who will come later,” he says.

Issues around recruitment are also often underplayed, he says, and sometimes not fully understood by clinical researchers. “They don’t always appreciate the demands that are being placed on patients to participate or the issues that participation presents to patients. Those sorts of problems are very real, very obvious on occasion.”

Mat Baker now supports other patient advocates and took the lead in developing a toolkit – a collection of resources designed to help patients and lay advocates have an impact and add value to the clinical research process (http://tinyurl.com/consumertoolkit). The expertise accumulated by the cohort of advocates like himself, who have been involved in the clinical research process for many years, is now seen as indispensable to development of the NCRI cancer trials he says.

Since the NCRI was established in 2001, recruitment to cancer clinical trials has shot up from fewer than 1 in 25 patients to more than one in five. Mat Baker says patient advocates are now a major force trying to push those rates up further.

“My personal view is that we should be aiming to double that, to a figure approaching one in every two patients,” he says, adding that the 2013 National Cancer Patient Experience Survey findings show that patients who participate in research record higher levels of satisfaction with their care. “We must therefore also have regard to the further extension of the opportunities to the benefits of participating in research.”

Expert patients for Europe

Although patient advocacy groups across Europe are keen to have more say in research that affects them and the in regulatory and health technology assessment processes that determine the therapies they can access, what they lack is the opportunity.

Some major cancer charities, such as the French Ligue contre le cancer and the Dutch Cancer Society, are helping to train expert patients to have an input into the research they fund. Governments outside the UK, however, have done little to encourage or facilitate patient involvement, and advocates continue to face scepticism and about the value they can add to research, if not outright resistance.

Into the breach has stepped EUPATI, the European Academy on Therapeutic Innovation, the brainchild of the European Patients’ Forum, and funded to the tune of €10 million through the Innovative Medicines Initiative – an EU–pharmaceutical industry partnership. EUPATI aims to boost the capacity of patient advocates across Europe to play an effective role with clinical trials, on ethics committees and within regulatory processes.

The communications officer, Rob Camp, comes from the world of HIV/AIDS patient advocacy, which pioneered engaging with research thirty years ago. He explains the EUPATI strategy. “There are three levels. The first is to educate and train 100 patient experts from all over Europe in the intricacies of the research process – everything from basic research in molecular development through to post-marketing and health technology assessment.”

This is done through 13-month online courses in two consecutive years, including two sets of four days spent in face-to-face meetings with the trainers, the first of which took place in Barcelona at the end of March.

These 100 ‘expert patients’ will be the ‘go-to’ people for other advocates from around Europe, says Camp.

The second level of training comes in online resources that national patient advocates can use in their own countries to help patient organisations to learn more, for instance, about specifics of trials, and apply the knowledge to their needs. These resources will be available in seven languages and fine-tuned at a local level for the needs of the 12 countries involved. Though designed primarily as “training of trainers” material, says Camp, it will ultimately be accessible to anyone who registers on the site.

The third level is aimed at the largest group. “Our goal is to reach 100,000 members of the general public who are interested in one way or another about health – their own or maybe someone in their family – and want information.

“There will be a toolkit available as well as news stories and so forth, which we hope will be interesting for them as they start to negotiate their own health systems on a local level.” These resources, aimed at the wider public, will also signpost people to the national advocates – the second level. “If they want to know more, they can go to the patient advocates in their countries to get more in-depth and specific information on any of the subjects they are interested in.”

A cultural revolution

Knowledge is power. However, while many patient groups will find the information and training invaluable in their quest to have a say in decisions about new research and treatments, Rob Camp accepts that information by itself is no guarantee that patient advocates gain access to the places where decisions are made. He says that this will mean opening doors on a case by case basis.

“People are still going to have to fight and knock really loudly to be let in. But at least once the door is open they will be somewhat equipped with information that will be useful for them. I think when patients start getting involved they will really become an added value to the process.”

Drawing on his experience in the UK, Mat Baker advises that changing the culture to accept the full involvement of expert patients in research requires a process of learning and confidence building, which can take time and determination on all sides.

When government policies started insisting on greater public and patient involvement, he says, many in the research community were yet to be convinced, and played along with varying degrees of enthusiasm. “As the confidence and expertise of lay people has gained ground, the contribution that they make has become valued and recognised. There has been some tokenism, but also I believe there has been a process of genuine collaboration that has evolved, and where it has evolved well, the benefits are very obvious and researchers are very positive about it, and would not consider pursuing further research without having that public and patient involvement.”

A shared approach to setting the research agenda

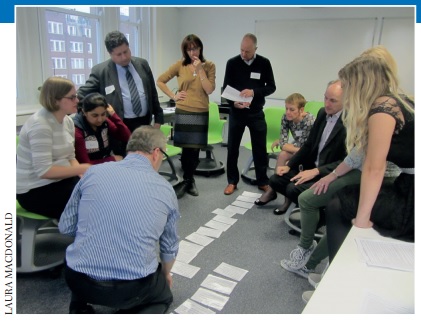

Last September a group of around 20 people including patients, carers and advocates as well as clinicians, researchers and other health professionals met in London, to define the 10 priority research questions for brain and spinal cord tumours. Participants were asked to rank their top and bottom priorities, from a shortlist of 25, explaining their reasons. The combined ranking that resulted was then fine-tuned into a consensus ‘top 10’ during a plenary discussion (see below).

The shortlist of 25 questions had been chosen by online voting from several hundred questions that had been gathered through surveying members of the professional and patient communities, and had been screened, using a Cochrane review-style process, to discard any that could be answered by existing evidence.

An equal voice

Kat Lewis (far left in the picture), a speech and language therapist, was impressed at how effective the priority setting process was at giving each participant an equal voice.

“It’s very rare that you get patients and their representatives, family and friends in the same room as quite senior and very experienced medics, and are able to get that level of consensus,” she said. “That’s the real testament to the process. It doesn’t always work as smoothly as it did on the day.

“There was a lot of respect for everyone else’s opinion. The views of someone who is currently facing cancer or has seen someone die from it are just as valid as the view of the neurosurgeon, who is usually held up as the pinnacle of medical knowledge.

“It did get a little heated towards the end, but everyone still kept to the task of ‘Let’s look at the bigger picture and think about what we need here, what questions are we asking, what are we looking to get funding for?’”

She attributes the success of the exercise in large part to having clear guidance and ground rules. “Where I’ve seen patient involvement fail is where the remit of the patients’ involvement hasn’t been clear, neither side is clear about what is meant to be happening, the meeting or group has no clear directions, and everyone ends up getting frustrated because they feel that it is not really changing anything.”

The process was facilitated by the James Lind Alliance Priority Setting Partnership and led by Robin Grant, lead for the neuro-oncology section of the Association of British Neurologists. Patient advocates were represented in the Core Group by Kathy Oliver, co-director of the International Brain Tumour Alliance.

The final top 10

1. Do lifestyle factors (e.g. sleep, stress, diet) influence tumour growth in people with a brain or spinal cord tumour?

2. What is the effect on prognosis of interval scanning to detect tumour recurrence, compared with scanning on symptomatic recurrence, in people with a brain tumour?

3. Does earlier diagnosis improve outcomes, compared to standard diagnosis times, in people with a brain or spinal cord tumour?

4. In second recurrence glioblastoma, what is the effect of further treatment on survival and quality of life, compared with best supportive care?

5. Does earlier referral to specialist palliative care services at diagnosis improve quality of life and survival in people with a brain or spinal cord tumour?

6. Do molecular subtyping techniques improve treatment selection, prediction and prognostication in people with a brain or spinal cord tumour?

7. What are the long-term physical and cognitive effects of surgery and/or radiotherapy when treating people with a brain or spinal cord tumour?

8. What is the effect of interventions to help carers cope with changes that occur in people with a brain or spinal cord tumour, compared with standard care?

9. What is the effect of additional strategies for managing fatigue, compared with standard care, in people with a brain or spinal cord tumour?

10. What is the effect of extent of resection on survival in people with a suspected glioma of the brain or spinal cord?

DIFFERENT PERSPECTIVES, EQUALLY VALID

Dr Stuart Farrimond can testify to the added value of including the patient perspective. He was diagnosed with a low-grade glioma midway through his training to be a general practitioner. When he was invited to participate in the priority setting exercise for brain and spinal cord tumours, he could therefore see each question from both a professional and patient perspective, and had to decide on his priorities. “The thing I was torn between is what is the most important from a clinical point of view, i.e. those things that are going to prolong people’s life the most, and those things that affect you on a day-to-day basis,” he says. In the end he opted to give highest priority to some of the questions that he felt would be most valuable to him.

“One of the questions was: how often should we scan people who have low-grade gliomas like I have. On the surface it doesn’t seem that important: Do you scan people every six months? Every year? Do you not scan? Is there another way to monitor them?

“From a doctor’s point of view the answer seems obvious. The more often you scan people the better it is, because you will be able to pick up any changes sooner, so you can act sooner. But from a personal point of view, having six-monthly scans is very emotionally draining. If someone told me: ‘Well actually if we only scanned you every year it would just make let’s say 5% or 2% difference to your overall outcome,’ that would be very useful for me to say, ‘Well on balance I think I’ll go down to annual scans.’ “You have the whole emotional thing that affects my wife, it affects me, it affects my family, waiting on the end of the phone to find out if it’s another all clear or if your life will be turned upside down.” He also chose to prioritise the question about whether lifestyle choices can influence tumour growth.

Thinking as a medic he understands that the effects of these choices are likely to be relatively small. “So I’d say actually it’s far more important that we research cutting-edge treatments, how to improve the chemotherapies that we are giving now, those will ultimately lead to a much better prognosis.” As a patient, however, he sees things differently. “When you are first diagnosed, you feel very out of control, and for many people in my situation you want to do something actively to improve your health and prognosis.”

In the absence of any proper evidence, he says, he spent months looking for things he could do that might make a difference. However, eating a lot of supplements, eating certain foods, avoiding others, impacted heavily on his family’s life as well as his own – and didn’t stop his tumour recurring.

After that he took a more pragmatic approach. “If somebody could say, for instance, there was a supplement that has evidence for being effective, that would be a very useful thing for people in my situation to know.”

He feels that the final list of 10 questions gave a fair representation of the priorities of all the groups who were there. “I thought the process was brilliant. The way you can get such a diverse group of people who all have their own agendas to come down to a list that everybody agreed on, or mostly agreed on, and that people compromised to get to, was an incredible thing.”

EUPATI – Training 100 expert patients

The first cohort of 100 patient advocates who will receive training via the EUPATI project are now more than halfway through their 13-month course. They come from 21 European countries and cover a wide spectrum of conditions and diseases. Among them is Véronique De Graeve (pictured below).

A few years ago she founded NET & MEN Kanker (net-men-kanker.be), a Belgian group for people with neuroendocrine tumours and multiple endocrine neoplasia, after doctors had failed for three years to correctly diagnose a NET in her mother. She says she found the course invaluable. “As a young patient group we have to learn so much, and are confronted with such a variety of issues that all need specific knowledge.

“Because of the complexity of those diseases and the need for new and better treatment options, this course is very beneficial to me. EUPATI trains you to be a competent stakeholder, to be able to communicate and engage on an equal level with all those involved in research and development.”

Getting your voice heard is a particular challenge for people with rare diseases, she says. “A better informed and educated patient group gives you more power: knowledge and education opens the door to so many things. You can become a voice for what you are standing for.”

Leave a Reply