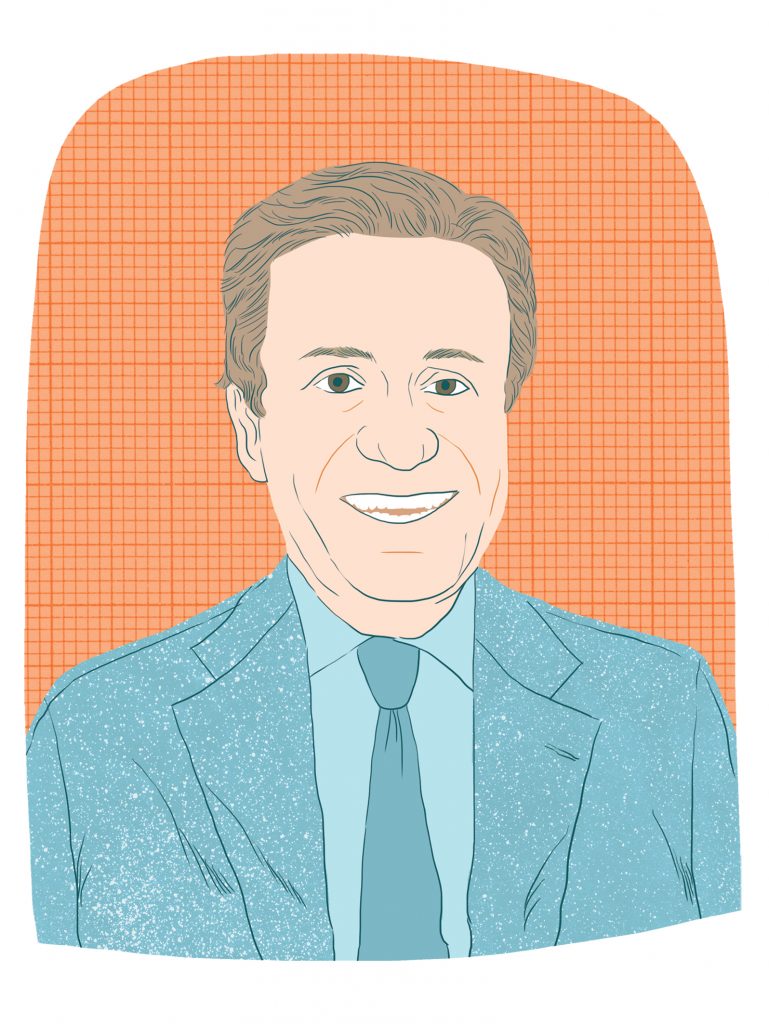

While holidaying on the Greek island of Ithaca, where the Odyssey ended, I met a man of my age and my country who had just finished his treatment for colorectal cancer. He now lives on Ithaca most of the year, returning home only in winter, and enjoys a simple life in a place where there is not a single traffic light, where appointments always have half an hour leeway, where you can ride your motorbike slowly, without a helmet, to enjoy the fresh air and the sun. He has reconciled himself with life – but he is still not happy with his experience of his cancer journey.

I am sure you always ask your patients if they have any allergies – patients certainly report that they are asked this question endless times. But do you ask what the person in front of you does, or used to do, in their life?

My new friend told me that he had never been asked about his profession, except on the first visit, to tick a box for the statistics.

“I was a senior pilot with Alitalia, and I was flying Rome–New York every week with my Boeing 747, and hundreds of people on board. But nobody seemed to be interested. For them I have always been simply ‘a cancer patient’.”

In effect, he was a file with imaging reports on his bowel, a nursing sheet with blood results, a name on the list of appointments at the day hospital, a dot on the graph that his doctor displayed on his poster at ESMO congress.

There is something wrong here, and maybe we should talk about it a bit more. A number of other issues seem to be much more important, of course, like this hammering topic of costs – the price of drugs, robotic surgery, proton therapy and – guess what’s next? – CAR T-cell therapy. But the fact that people feel that they lose their identity when they become ‘a cancer patient’ should made us think.

Firstly, because it could be our turn one day. Would we like that? I’m not so sure, particularly as we would inevitably start asking a lot of questions and have a lot of concerns arising from our own professional experience. But secondly, because it is impossible to be only ‘a cancer patient’. We would be a doctor or a nurse with cancer, or a Boeing 747 pilot with cancer, as my friend, or a farmer with cancer or a school dinner-lady with cancer.

Knowing more about our patients may not improve their survival rate, but it would certainly improve their experience of being a patient and survivor. Can we give it a try?