Clinicians around the world use NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology as a standard for clinical decision-making. The NCCN Harmonized Guidelines are targeted regional resources created as part of a collaborative effort to combat the skyrocketing cancer rates and unique care circumstances.25 new guidelines will be available by the end of the year 2018 to help fighting cancer in sub-Saharian Africa. Like it happened for HIV, experts hope to control the disease starting from well organized, appropriate low-cost intervention

When Gloria Orji Ishioma was diagnosed with stage 2 breast cancer in Abuja, Nigeria, in August 2010, she knew little about her disease. She was able to receive good support and, after a five year journey of chemotherapy, surgery and radiotherapy, she was able to overcome the disease. But it came at an exorbitant cost to her, and her siblings chipped in to help her pay the bills – which is not an option every patient has.

“When I found out about my disease, I felt my life has literarily stopped. I remember asking my doctor how long I had to live because I felt it was a death sentence,” says Ishioma. At that time, she knew very little about breast cancer or her treatment options.

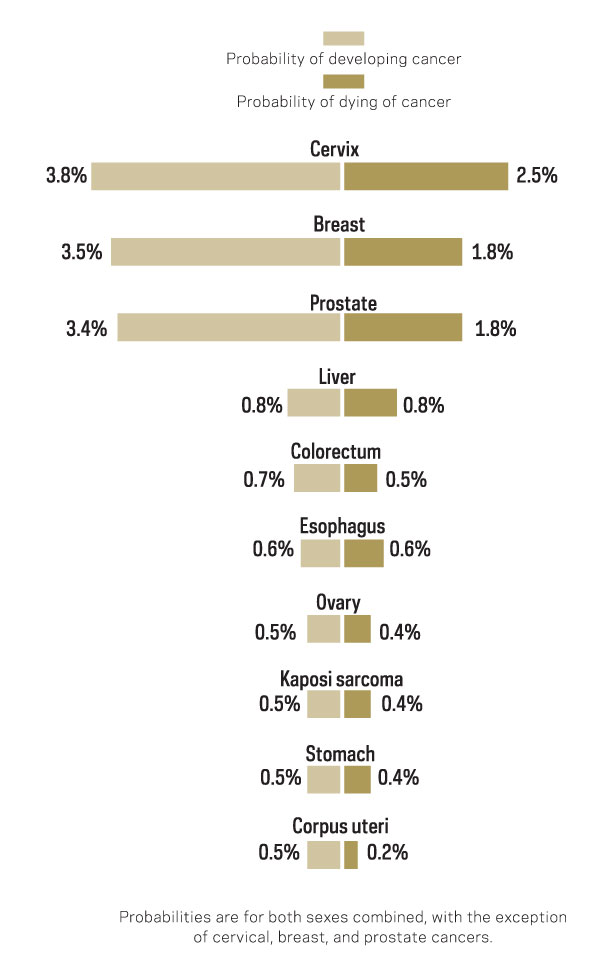

Traditionally, cancer was not really sub-Saharan Africa’s biggest healthcare problem. Communicable diseases, such as pneumonia, malaria, and HIV/AIDS, have always been the biggest killers. In 2015, these diseases claimed the lives of 5,2 million people in sub-Saharan Africa – compared to around 530.000 people dying from all the different types of cancer.

However, population aging and growth, economic growth and the increased prevalence of key risk factors have sent the number of cases of cancer rising sharply over the past decade. The resources-restrained continent is struggling to deal with this change. According to the International Agency for Research on Cancer, the annual number of new cases of cancer in Africa will grow to over one million over the next five years.

The lack of healthcare systems

Governments and aid coming to Africa has normally focused on communicable diseases – and have successfully reduced deaths from these – but the side effect is that they did not build healthcare systems able to effectively deal with non-communicable diseases. For example, according to The Cancer Atlas, 80% of people diagnosed with cancer across sub-Saharan Africa are already in advanced stages of the disease, and fewer than 10% receive pain relief, chemotherapy or radiotherapy.

According to a paper published in the Journal of Global Oncology (J Glob Oncol. 2015 Oct; 1(1): 30–36.), there are only 102 cancer treatment centres in Africa. This is far below the needs of the continent’s growing population.

“There’s a dramatic shortage of specialist oncology caregivers in Africa,” says Robert Carlson, MD, CEO of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN). “Those who are there are very bright and dedicated, but do not have access to the latest equipment and technologies.”

Guidelines for low resource countries

The NCCN regularly produces and updates treatment guidelines for the different types of cancers, and they are widely adopted around the world as standards for treatment. They are, however, developed mainly for high resource cancer centers. This means they may not be relevant in the sub-Saharan Africa context, where the average total health expenditure per capita amounts to only US$82.

While granting doctors and patients access to the latest advancements in treatment may not be a realistic option, sub-Saharan African countries need to address this rising danger quickly and make sure citizens have a basic level of cancer care. That is why NCCN produced a new set of harmonized guidelines specifically tailored for the on-the-ground realities in this region.

“We want to make sure that even if resources are limited, people can still get the best possible care. I don’t look at this as limiting care for Africans, but as aspirational – how can we best use what resources we have to maximize effect and care” says Carlson.

In order to come up with this special version of the guidelines, the NCCN worked closely with African clinicians and oncology experts from the African Cancer Coalition, a group of oncologists from 12 African countries, to make sure they are relevant to their and their patients’ needs. “We not only involved experts, but also health ministers, research centres and other NGOs so that what we have is comprehensive” adds Carlson.

Tailored treatments for each area

The experts from NCCN also work with their sub-Saharan counterparts to try to identify what areas of development would have the biggest effect on improving care, in order to create some direction for the future growth of cancer care in the region.

Ishioma says that, living in the capital, she was able to get the treatment she needed fairly easily. In rural areas, however, it is a different story. “Diagnosis is often delayed due to ignorance and misdiagnosis is common. This accounts for the high rate of cancer deaths in the country”.The high costs of treatment often force poorer people to resort to herbalists or faith healers instead of seeking medical care.

Carlson is hopeful the special guidelines for sub-Saharan Africa can solve many of these problems. The guidelines use a colour-coding scheme in order to denote the best treatment options based on the availability of resources, acknowledging there are large differences between capitals and far-flung villages in sub-Saharan Africa when it comes to healthcare resources.

For example, the most effective treatment for cervical cancer is radiation therapy, but it is not widespread in Africa due to the lack of equipment in cancer centers. “Instead of no treatment, in select circumstances, we recommend chemotherapy followed by surgery as the second best option through the guidelines” says Carlson.

The most common cancers in sub-Saharan Africa are breast, cervical and prostate cancer. The NCCN harmonized guidelines offers two tiers of treatment recommendations for these diseases, depending on access to resources like radiation equipment or specific surgical tools.

Spreading the word about guidelines

Developing these guidelines is only the first step. Unless they are spread and adopted in cancer centers in the region in order to bring the best possible care to as many people as possible, they will never really be useful.

The harmonized guidelines are freely available for anyone to access and download, and IBM is developing an app to make it more accessible, especially in Africa where internet access is mainly through mobile phones.

But Carlson and his team are counting on the sub-Saharan African individuals working with them to really take on the responsibility of spreading the guidelines. There are already around 60 practitioners from the region involved in the project, which is a substantial percentage of the total in sub-Saharan Africa. They are best positioned to act as advocates for the harmonized guidelines.

“We do know that cancer care practitioners around the world are aware of the NCCN guidelines, so we hope these guidelines will eventually spread around” adds Carlson.

So far, NCCN has produced eight of these special guidelines, and roughly another eight are expected to be published within the next month or two. By the end of the year, this number should have increased to a total of around 25 guidelines especially formulated for sub-Saharan Africa and regions with limited resources. Each of the guidelines looks at either one type of cancer or one area of care.

“Within my support group, we are always getting complaints about how expensive treatment is. This is our biggest challenge” says Ishioma. “Also, after proper diagnosis, patients in rural areas often have to move to a different region with facilities for cancer treatment exists”.

These are the challenges that HIV/AIDS treatment in Africa faced about a decade and a half ago. Since then, care providers and pharmaceutical companies have been able to bring the cost down significantly and identify the best interventions to control the disease, which had brought treatment to tens of millions of patients in Africa.

By modeling their efforts to control cancer to that successful approach, these cancer care experts are hoping they can achieve the same results before cancer gets out of hand across sub-Saharan Africa, as it is poised to do over the next 10 years.

Leave a Reply