As a journalist, I often wonder about the exact location of the fine line that separates justified enthusiasm from self-serving hype, especially when it comes to clinical trials.

Last week, I asked the question of an excellent physician and researcher I was interviewing, specifically showing him a story just published by STATnews that announced a “major blow for immunotherapy combination treatment”: he agreed with me that it is important not to convey to the public – and especially to cancer patients – an excessively optimistic image, but still reaffirmed that in his view being enrolled in a clinical trial is totally worth, for a patient with few and modest available choices. In that specific instance I have many reasons to believe that he is in good faith when he says that the “blow” only affects the specific approach used in that trial, and not the whole field, but still I was not fully satisfied by that part of our conversation.

One of elements that helped me make up my mind on his unquestionably good faith is that he works in a public hospital, and attracting more patients implies more work and trouble, without financial rewards.

This of course doesn’t mean that there are no other interests potentially in conflict with the patients’ best interest, but the situation is likely much simpler than it is elsewhere – and particularly than the one described in a recent article published on Jama Oncology by ethicists Alex John London and Jonathan Kimmelman (“Clinical Trials in Medical Center Advertising”).

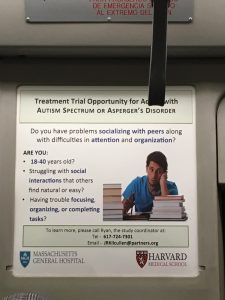

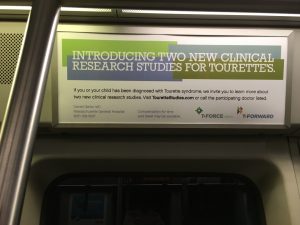

Of course I know a lot about medical research in the United States, but I had a first-hand surprise when I started to notice so many advertisements related to clinical trials in the metro of Boston/Cambridge (where I spent a year as Research Fellow at the Knight Science Journalism program of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, last year). Some of those ads – displayed in this page – felt to me like a mixture of overselling and disease mongering.

Now the analysis by London and Kimmelman provides a detailed explanation for my gut feelings, listing a long series of questionable practices that appear to be common in the US: “Such portrayals of trial participation involve a 2-way transfer of associations: the prestige of research is marshaled to elevate the reputation of the medical centers and the therapeutic mission of medical centers is invoked to bolster participation in clinical trials. Although this reciprocal branding of clinical trials and medical centers may increase trial participation in the short term, the therapeutic branding of studies perpetuates misconceptions that distort patient expectations and nourish movements that would weaken the research enterprise” they write.

One of the classical “tricks” (in good faith? Who knows!) goes like this: “Every improvement in cancer treatment has been the result of rigorous clinical trials”. It is self-evident, right?

Well, only in part, argue the ethicists, since the statement invokes the inverse fallacy: “The probability that lottery winners purchased tickets from convenience stores might be high, but the probability of winning the lottery if you buy tickets from convenience stores is very low”.

Their conclusion is strong, and I think we should all keep it in mind when discussing about the value of clinical trials: “A core mission of academic medical

centers is the generation of scientific knowledge that advances patient care. Using trials to attract patients undermines that mission in pernicious ways. Such messages imply that persons accessing unproven treatments are at a medical advantage over those who cannot access those treatments. This same claim animates movements such as the ‘right to try’, advocates of less-stringent drug regulations, and clinics that market unproven cell-based interventions directly to patients. In using their commitment to science to attract patients, many medical centers ironically reinforce the message of those who would diminish the role of clinical trials in drug evaluation” they conclude. “Meeting the demand for clinical trials that such advertising generates also potentially encourages medical centers to offer trial options even where scientific rationales are weak. Although on its face, more research is better, not every clinical challenge has hypotheses of sufficient maturity to justify the expenditures of time and capital required for testing”.

Of course, we also have to keep in mind that when we adopt such a critical approach to medical research we – journalists, ethicists, patient advocates and even medical professionals – risk being tarred and feathered by some as anti-science. It’s weird, but I ended up accepting this among the risks of my profession.