For most of us, sooner or later, old age will bring frailty and chronic health conditions, making the task of living the life we wish progressively harder. We will want oncologists who know what different treatment options can offer people like us. Peter McIntyre asks: how can we do better for older patients?

“My mother believes she is immune to breast cancer,” says surgeon Riccardo Audisio. “That is because they don’t send screening letters to women older than 70.” He hopes his mother stays safe, but suspects that if she did develop breast cancer she would probably see it as the end.

“It is a general assumption that when you are old you don’t get cancer, and if you do get it, it is untreatable, which is the exact opposite of the truth. Age, per se, is the primary risk of developing cancer, and older cancer patients are as treatable as younger ones.”

In practice, older patients do not get treated as well as younger patients and they do not survive to the same extent. There is an increasing mismatch as older age groups in Europe have a growing proportion of cancers but are less likely to be treated with surgery, chemotherapy or radiotherapy. They are much less likely to be represented in research.

Nor do older people have a voice in policy discussions about cancer. There are few special advocacy services for older people; and this is the age group most likely to trust their doctors and go along with whatever treatment is suggested.

Worse survival

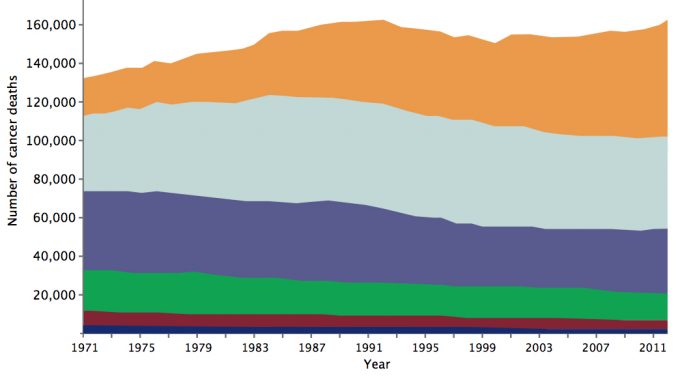

The EUROCARE 5 Study showed that five-year relative cancer-specific survival in Europe (2000–2007) decreased with older age for all cancers (Lancet Oncol 2014, 15:23–34). The age standardised death rate for cancer was more than 12 times higher among people over 65 than for younger people (Eurostat 2015). Data from England show the rising trend of cancer deaths in the 80+ age group has the steepest trajectory.

Older patients are more likely to be admitted for cancer as a result of an emergency and more likely to be diagnosed very late (stage 4) (Br J Can 2015, 112, S108–S115). A study comparing colon cancer patients in England, Norway and Sweden showed excess deaths in older age groups, and most occurred within three months of diagnosis (Gut 2011, 60:1087–93).

Most people accumulate health problems as they age. Cancer is often treated against a background of diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, stroke and hypertension. More than a third of people over the age of 80 are being treated for four or more medical conditions (Lancet 2012, 380:37–43).

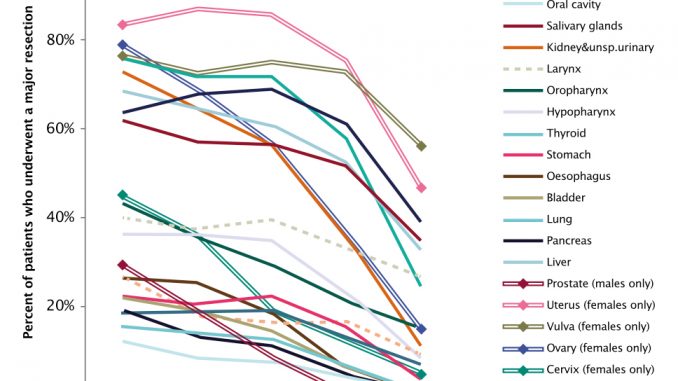

However, treatments most commonly associated with cancer cure are less commonly given in this age group. The National Cancer Intelligence Network in the UK says that older patients are less likely to receive surgery, radiotherapy or chemotherapy, and most specialists say that this is the case across Europe.

Assessment

Siri Rostoft, a geriatrician at Oslo University Hospital, says that every older patient should have an assessment of some kind before treatment decisions are made. A comprehensive geriatric assessment takes about an hour, but simpler tests can be used when time is tight. The critical factor is to look at the person’s condition rather than simply counting the years, as older people show great differences in physical and mental resilience, and these differences increase with age and can be predictive of outcomes.

To illustrate the point, Rostoft mentions the case of a 94-year-old woman admitted to the acute geriatric ward with fatigue and dizziness. She was found to have anaemia and bleeding due to a right-sided, narrow passage, large colon cancer. At her age, she seemed a doubtful candidate for surgery.

After her condition stabilised, Rostoft conducted a simple Timed Up and Go test (TUG), asking her to get up from her chair, walk three metres, return to her seat and sit down. If this takes longer than 19 seconds, the person is classified as frail and a full assessment may be needed. The 94-year-old woman insisted she wanted to take the test starting from lying on the floor, as doing it from sitting would be too easy. She completed this much more demanding test, and was passed fit for surgery.

Rostoft accepts that not every elderly patient can have a gold-standard comprehensive geriatric assessment, but even simple gait speed tests have been shown to have strong prognostic power. She points out that a fit 85-year-old in northern Europe can expect to live a further 10 years – twice as long as the five-year survival gold standard used for clinical trials.

Cancer mortality is falling – but not if you’re over 80

“Oncologists may argue that there is no way they can spend one hour with a patient. But if you want to give someone chemotherapy which is extremely expensive and toxic, you have to spend enough time before you start treatment. The risk of delirium and becoming confused and not cooperating with the treatment is much higher if the patient has cognitive impairment, and you often have to do some objective tests to uncover that.

“I have experienced a few times when an oncologist calls me because the patient became confused in the ward and starts pulling out needles and refuses to do anything the doctors and nurses tell them to do. I think they should have called me before they started treatment, because maybe there were signs that could predict what would happen, and we have interventions that may prevent delirium.”

Pierre Soubeyran, a geriatric oncologist who coordinates the Geriatric Oncology Research Group at the Bergonié Cancer Institute in Bordeaux, agrees that assessing a patient’s overall condition is critical.

“The older you get the more comorbidity you have and these comorbidities interact, especially medications and side effects. There can be very negative outcomes for these patients if we do not treat them correctly, because oncology treatments are toxic.

“What oncologists find most difficult are what they call the geriatric syndromes that concern nutrition, cognition, mood, mobility and functionality, which make the patient’s reserves very limited. That may not be visible at first look.” For example, he says, it could be dangerous to give oxaliplatin, which can cause balance problems, to someone with colon cancer who already is unsteady on their feet.

Soubeyran and his team developed the G8 assessment now adopted throughout France, asking questions about food intake, weight loss, BMI, mobility, neuropsychological status, number of medications, and self-perception of health status.

They are now working on a slightly broader assessment that can be used by an oncology team. “Oncologists are always in a hurry and the tools that geriatricians propose feel too complicated. The objective would be a 15- to 20-minute assessment performed by a nurse. What we are proposing is to make the evaluation much more methodological, clear cut and defined.”

Soubeyran says that many oncologists work on the basis that if someone looks very old they should decrease the dosage, and this can lead to undertreatment. “Some patients look frail, but the evaluation shows they are not. My experience is that most of the time an evaluation leads to treatment at or close to a normal level.”

However, Siri Rostoft does come across some cases of overtreatment, particularly in very frail ‘young elderly’ patients in their late 60s and early 70s.

“I have seen a small number of patients where, once they have started cancer treatment, it is difficult to have the discussion on when to stop. In some cases it is obvious that the patient is not benefiting, as the treatment is too aggressive and the side effects clearly outweigh the benefits. The assessment has to be individualised to aid decision making, so as not to overtreat frail younger patients or undertreat the really fit older patients.”

Access to surgery

There are also concerns that elderly cancer patients are often excluded from surgical treatment. Riccardo Audisio, who is President of the European Society of Surgical Oncology and professor of surgery at Whiston Hospital, Liverpool, says that low rates of surgery for old patients in the UK reflect what is happening across the world.

“Surgery is the curative option for cancer, and there is evidence that surgery is not routinely offered to older cancer patients on the grounds of their age. There is a substantial discrimination that starts from the very beginning. A woman has had peri-rectal bleeding. She is now noticing blood in the stool but she does not tell the family. When told, the family does not tell the GP and the GP does not send her for a proper investigation because she is old.

“The most shocking thing is most older patients come with the assumption they are not fit for surgery. You have to spend a little bit of time with your patients and clarify that surgery is not as dreadful as they expected.

“You explain that half the patients we deal with or more are their age, and anaesthesia is very safe. And surgery can be performed. In some cases I tell them, if I take the breast cancer out you can go home the same day and you can walk your dog.”

Surgeons need face-to-face contact to build trust with the patient. “This is a very delicate moment. When they sign a consent form you are telling the patient ‘I bet money we will get out of here quite easily’ or you are telling them ‘It is going to be a challenge and the risks are high’. I cannot expect a geriatrician or nurse to discuss these delicate issues for me.”

Geoff, 66 – surprised by ageism

“What surprised me most was a discussion about my treatment options. I was told that I could have surgery to remove the tumour if the cancer hadn’t spread. But they explained that if I was over 70, they may not have o ered to operate at all. I thought that was discriminatory, and clearly ageist. The role of the medical profession is to prolong life, no matter what age.

Surgery could give someone another 20 years.Macmillan Cancer Support. (2012) Age Old Excuse: The under treatment of older cancer patients

Audisio says that one reason why surgeons become cautious is because they are judged on operating mortality rates. “If you are on call over the weekend and you have three older very frail patients admitted as an emergency for bowel obstruction and you know that mortality is three times higher for an elderly emergency colorectal patient, do you operate or say, ‘they are too old and too frail,’ and just leave it?”

A 2016 survey by the Surgical Task Force at the International Society for Geriatric Oncology (SIOG) shows that 90% of surgeons operate for cancer regardless of age; but half would not operate on a patient with impaired cognitive status. Less than half think preoperative frailty assessment is essential, and only a third regularly collaborate with geriatricians. Quality of life and functional recovery were regarded as the most important endpoints. The study team concluded that age is not seen as a barrier to surgery, but there is a need to focus on ‘prehabilitation’ to achieve better functional recovery. The survey may present an optimistic picture, since the 250 surgical oncologists who responded make up only 11% of those who were asked, and possibly have more positive attitudes.

What does the patient want?

Lower rates of treatment do not seem to be due to a reluctance on the part of the patient. A 2014 report by NHS England found that older people are more likely to have confidence in doctors and nurses. Research carried out by a polling organisation for Macmillan Cancer Research in the UK, published in 2015, shows that the proportion of patients refusing cancer treatment actually falls slightly amongst older patients, with 12% refusals among patients over 75 compared with 15% amongst 55- to 64-year-olds.

It also showed that older patients are more likely to feel they can ‘cope’ with cancer, and this may be driven by the desire to maintain independence. Overall, maintaining health is listed as the most important priority for most people living with cancer, but in the older retired group continued independence (44%) is just as important as maintaining health (43%).

Hearing the patient voice is especially important given the increasing understanding that patient-reported outcomes can be a very reliable indicator of how a cancer patient is progressing.

Siri Rostoft says that the only way to find out patient priorities is to ask them. “A basic thing that is often not done is to talk to the patient and to discuss it. Some patients have really strong opinions and say ‘no way that I want to go through any treatment’. My impression at least is that older patients still have some paternalistic idea that the doctor knows best, and say, ‘do what you think is right.’ Others say, ‘talk to my son or my daughter – she will know better than me.’”

Uncovering patient priorities is challenging if there is cognitive dysfunction. “Cognitive function affects physical function, and physical function is an extremely important predictor of life expectancy. It is more demanding when they cannot say clearly what they want and they don’t understand. We talk to them about the cancer and treatment options, and the next day they don’t remember that they have cancer.”

In these cases it becomes increasingly important to include the family and care givers and take more time over explaining the options.

Pierre Soubeyran says that some older people are very skilled at hiding their confusion. He recalls a 95-year-old woman becoming very upset when asked questions designed to test her memory. “Initially when I saw the lady I did not see any cognitive problem because she was very clever and cultured and was able to circumvent the cognitive problem and answer questions. In the end, we realised that she was deeply impaired, and it was important to know that. It may change the way the patient understands what we explain.”

Francesco De Lorenzo, President of the European Cancer Patient Coalition (ECPC), says there are virtually no specialist advocacy groups in Europe for elderly cancer patients, and condition-specific cancer organisations are generally not geared up to represent them. He sees as crucial providing support to family or other caregivers, who in Italy support eight out of ten older cancer patients. ECPC will be pressing the European Parliament to introduce new rights for carers and elderly people with comorbidities, who are often very severely affected by reductions in home and social care.

Jim 73 – independence threatened

Jim has lived alone since his wife died. After he was diagnosed with cancer of the throat, he had a tracheostomy. Hospital sta wanted to send him to a nursing home as they said he could not cope at home.

“I was getting very angry because I was told that the district nurses could help me with this but none of them had been trained to do so.” He was found an advocate, Richard, who talked to sta at the hospital with him. “He understood that I wanted to go home and be independent. I am not quite sure how much Richard had to do with it, but the district nurses were given a rapid training course in tracheostomy management and I was allowed home.”OPAAL (UK) and Macmillan cancer support case studies. (2014) Every Step of the Way

One of the few advocacy services for elderly cancer patients and their families is showing results, from improved clinical communications to reduced financial anxiety, improved hope for the future and enhanced self-respect. Cancer, Older People and Advocacy was launched in the UK by the Older People’s Advocacy Alliance (OPAAL), with funding from the national lottery and Macmillan Cancer Support.

Operations manager Marie McWilliams says that advocates can attend hospital consultations with cancer patients and help them to understand their choices. “Sometimes people feel they should make decisions on the spot. The advocate will reassure the older person that they do not need to make a decision there and then. They might want time to digest the information. The advocate is the calm level head who will take detailed notes.

“A lot of people who come to us are also the main carer for somebody else and put their own care and treatment to the side. We need to be aware that the person who gets the cancer diagnosis has the same issues and worries in their life they had before the diagnosis. Cancer happens to be something they add on to everything else they have in their life.”

Beryl 84 – Left alone to cope

“Iwas shocked to be diagnosed with bowel cancer, as I’d had no symptoms or pain. I was told I’d need surgery to remove half my bowel.

I’m a widow and live on my own, so after the surgery my son came to give me a lift back to my at. After I was discharged from the hospital, I was left to look after myself – I didn’t even get a wheelchair to get down to my son’s car. I wasn’t o ered hospital transport or help to cover the cost of taxis to and from appointments.

When I got home the rst week was awful. I lost a lot of weight as I couldn’t eat after the

surgery. I couldn’t wash myself or clean the at, which made me feel very depressed. I had no idea who to speak to for help, and no support when I needed it the most.”Macmillan Cancer Support. (2012) Age Old Excuse: The under treatment of older cancer patients

OPAAL is seeking sufficient funding to extend the service around the country to ensure that older people do not face discrimination in treatment. McWilliams says: “Those who discriminate should realise they can come become victims of discrimination too. If I am lucky I will live to be old enough to face age discrimination. Something needs to be done about it.”

Left out of research

Older cancer patients are largely excluded from research. The National Cancer Patient Experience Survey in the UK showed that, while a third of patients aged 51–65 were invited to take part in research, this dropped to around 20% for those aged 75 plus. Of those who were asked, half agreed to join a research project, but only half of those who agreed were enrolled.

Ten years ago Soubeyran was part of a SIOG team who met with pharmaceutical companies to discuss how to include more elderly patients in trials. “They said it was good idea, but I did not see any changes. Probably they don’t want to have frail patients who may encounter more side-effects and complications.” However, he says that industry is waking up to the increasing number of old patients, and that they will benefit from a more positive approach.

The European Medicines Agency is putting pressure on industry to make clinical trials more representative of the population to be treated. The summary of product characteristics (SmPC) for each new medicine should give specific safety information and dosage considerations for elderly patients. Post-authorisation, companies will be expected to present separate information about adverse effects on patients by age band for those over 65, 75 and 85 years.

The International Society for Geriatric Oncology has been developing its own guidelines on treatment of solid tumours and haematological malignancies, which are posted on its website (www.siog.org).

Matti Aapro, a founding board member of SIOG and a Director at the Swiss Genolier Cancer Centre, says that oncologists need more guidance on risks and benefits when treating frail elderly patients. “Regrettably most studies that include elderly patients address those I call the ‘Olympic champions’ of oncology, as they fit all the criteria for inclusion. We need studies that look at patients who have restrictions to see how best to apply treatments without guessing on what is the best way to go.”

He too sees signs of change. “In the past 20 years we have seen a steady growing interest and people have become more aware of the need for studies. Industry is now very receptive to the need for specific guidance for elderly patients.”

Prehabilitation: going the extra mile

Zohra Khan, aged 71, had breast cancer in her 60s and was treated with surgery and radiotherapy. This year she was diagnosed with a neuroendocrine cancer and was assessed at the Churchill Hospital, Oxford, as a candidate for whipple surgery to remove the tumour from the top of her pancreas. To take a cardio-pulmonary exercise test, she had to get on a bicycle for the first time in her life and pedal. The test showed that her physical condition was poor, but her surgeon urged her to take some exercise and try again. For three months she has been walking every day and using an exercise bike that her daughter Jabeen installed in her front room. In September 2016 she was reassessed and was declared fit for surgery. Zohra Khan is nervous about the operation, but is delighted that the surgeon helped her to get fit.

The SIOG annual conference in Milan this November will include special sessions in collaboration with industry, to put some of these issues under the microscope. There will be a special focus on immunotherapy. Aapro says: “The question that everyone is asking is: Can we apply the new immuno-oncology drugs to the elderly? and the answer is a clear ‘yes’. We have evidence that elderly patients can benefit from these types of approaches without undue toxicity.”

Research is also needed to show the impact of pre-treatment assessment. Soubeyran is recruiting 1,200 patients for a randomised trial based at Institut Bergonié, supported by the French Ministry of Health, to see whether a full geriatric assessment by a geriatrician and nurse before treatment results in improved outcomes. Endpoints for this PREPARE trial will be one-year survival and quality of life. “We will consider there is a benefit if we improve survival without decreasing quality of life or if we improve quality of life without decreasing survival,” says Soubeyran.

Audisio is doing something similar in the surgical field. The Go Safe trial is recruiting 360–400 cancer patients who are candidates for surgery from the UK, Italy, Netherlands, US, Canada, Germany, Switzerland and Austria. Following an initial assessment of frailty, nutrition and psychological wellbeing, they will be treated according to the judgement of their surgical oncology team and followed up at six months and a year to see if there is an association between outcomes, the original assessment, and the treatment they received.

Audisio says: “The hypothesis is that by optimising the patients’ weaknesses and frailty, nutrition, depression, anaemia, cardiac and so on, we will end up with a shorter hospital stay and reduced costs, less mortality and so on.”

For geriatrician Siri Rostoft, research must include cognitive function, comorbidity and functional status, both as predictors and as outcomes. “It is not only five-year survival or progression-free survival that counts; maybe functional status counts more. The new cancer drugs are extremely expensive, but maybe less toxic and we have this huge population of older cancer patients who should get them. Who will make those decisions?”