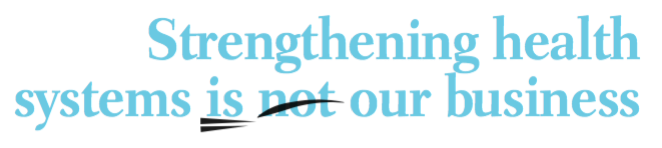

A narrow focus on cancer prevention, detection and care can only succeed as part of wider efforts to strengthen public health systems.The cancer community needs to

start playing its part in that effort.

Health systems strengthening (HSS) has become the new focus for global health. The strategy is enshrined in the Sustainable Development Goals and calls for universal health coverage, but it dates back to the 1978 Alma Ata Declaration of Health for All.

Since 2005, resources and attention have shifted from disease-specific approaches to strengthening health systems. HSS is described by the World Health Organization as a single framework with six ‘building blocks’: service delivery; health workforce; information; medical products, vaccines and technologies; financing; and leadership and governance (stewardship).

These sorts of ‘building blocks’ for health are much loved by academics and policymakers. There are as many variations on HSS as there are stars in the sky, from diagonal approaches to complex investment models. Whilst a great deal of the HSS discourse is, frankly, ‘ploughing the sea’, there is a serious issue. This is the conceptual framework around which funding for global health now fits – be it research, official donor assistance or structural funding from bodies like the IMF. So the question is, how does cancer fit into this ‘new’ paradigm?

“Cancer control can only be built

on strong existing health systems”

Firstly it’s worth pointing out that cancer control (prevention, early presentation, affordable high-quality control, cure and palliation) can only be built on strong existing health systems. I’ve made this point before (Cancer World Jan–Feb 2016): health systems that are not properly funded and structured de facto will never be able to deliver affordable, equitable cancer control.

The cancer fraternity tends to get somewhat wrapped up in its own world, but we also need to advocate for better public health for all. It’s clear that, as a global community, cancer has not been universally good about building resilience into nascent and emerging cancer control systems, to help them weather political unrest, economic turmoil and man-made disasters such as the conflicts in Libya and Syria (Lancet 2016, 388:207–10).

Serious investment as a public good by wealthy countries and research funders can and does pay dividends in building the health and cancer workforces of tomorrow (Lancet 2013, 381:2118–33). We need to do much more of this, and not treat it as exceptional.

Real improvements in cancer outcomes are composite endpoints of systems – social systems, which determine when and how patients present, and health systems, which are only as good as their weakest component. It’s easy to see why approaches to cancer control have predominantly been technocentric and specific to particular modalities (medical oncology, surgery etc). That’s the way the money flows.

“It’s time for the cancer community

to stop being parochial, and focus

on building pathways of care”

If public and industry funding were rational and followed patient outcomes, then they’d only ever fund through multidisciplinary structures. Looking from the outside, it defies rationality to advocate for access to cancer medicines in countries unable to deliver the most basic system for cancer surgery.

When disease-specific funders such as the GAVI vaccine alliance are investing in HSS, it’s time for the cancer community to stop being parochial, and focus on building cancer systems and pathways of care. So how do we go about this?

First we have to recognise that there is a real-politik to cancer systems, and that is their breathtaking complexity. Moreover the concept of health systems strengthening for global cancer remains vague, and there is a weak evidence base for informing policies and programmes for strengthening health systems generally (Health Policy Planning 2013, 28:41–50). But both these hurdles are surmountable.

Funding could and should be directed at cancer systems research, and we need to recognise that health services research is not a poor cousin, but the lifeblood for evidenced-based cancer control plans. The disciplinary approaches also need to breach the orthodox boundaries to embrace political economy, social science and all manner of disciplines capable of shedding light into the darkest recesses of cancer systems.

We also need to recognise that the discourse we have in high income countries about HSS and cancer are of limited relevance to many countries that have fragmentary, low-capacity and discontinuous health services. Radically different thinking and approaches are needed here to get cancer into the mainstream of HSS. John Kingdom, one of the doyen’s of public policy, argued that issues get onto policy agendas when three independent streams – problems, policies and politics – flow together (Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies 1984; Little, Brown).

Defining cancer as a systems problem would go a long way to neutralising onco-tribalism, and make cancer a more cohesive global force in health systems. So too would embracing policies relevant to social determinants, as well as the structures and organisation of cancer care. The slavish adherence to cancer as a technical problem puts it at odds with a lot of the conceptual underpinnings of HSS.And finally, the politics of cancer needs to move away from the non-communicable diseases ‘box’ and into the areas that really matter to HSS, such as development and the equality agenda.

Richard Sullivan – Director of the Institute of Cancer Policy, and Conflict and Health Programme, at Kings Health Partners Comprehensive Cancer Centre, London

Leave a Reply