If detected early, 80/90% of head and neck cancers can be cured. Yet lack of awareness means that two out of three cases are picked up late. The Make Sense campaign takes a message of hope to the streets and subway stations and to the media and politicians.

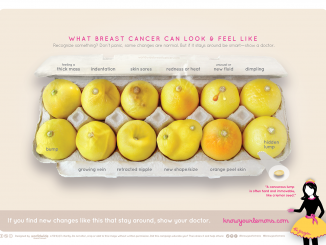

Advocacy and awareness campaigns have transformed public attitudes to cancer in recent decades. By challenging the silence and taboo associated with the disease, they have promoted life-saving messages about risk factors and symptoms and put access to prevention, screening and high-quality care onto the political agenda.

The breast cancer lobby, with its ubiquitous pink ribbon, was first and the most successful. Other advocacy networks followed, such as for prostate cancer, leukaemia, and brain tumours. Conspicuously absent from the list has been head and neck cancers, although they seem ideal candidates for advocacy. The sixth most common cancer in Europe, they have recognisable symptoms, and if detected early can be cured in 80–90% of cases. Yet lack of awareness among the public and primary healthcare professionals means that two out of three cases are currently picked up at a late stage.

Patients treated for head and neck cancer have a pressing need for help to rebuild their lives after treatment, when disfigurement to the face and loss of ability to speak or swallow normally can leave them feeling isolated and unable to pick up the strands of their lives.

Jean-Louis Lefebvre, president of the European Head and Neck Society, has been preoccupied with the question of why head and neck cancers have remained in the shadows for so long. Last summer he spoke to Cancer World about his efforts to promote greater awareness, especially among those most at risk (Breaking Boundaries, July–August 2012). The fruits of his labours were realised this September with the launch of Make Sense (www.makesensecampaign.eu), a Europe-wide campaign, led by the European Head and Neck Society and supported by Merck Serono, Transgene and Boehringer Ingelheim, that aims to raise the profile of head and neck cancers.

Make Sense has three target audiences:

- The public – to raise awareness about head and neck cancers, risk factors, symptoms, and the importance of getting symptoms checked early,

- Health professionals – to improve early detection, treatment, care and rehabilitation,

- Policy makers – to advocate for governments to ensure equal access to high-quality services.

The foot-soldiers of the campaign are members of national affiliates of the European Head and Neck Society, who helped to launch the “First European Awareness of Head and Neck Cancer Week”, with five days of action coordinated across 13 countries.

Into the streets

For Ana Castro, a medical oncologist and member of the executive board of the Portuguese Head and Neck Cancer Society, the week offered an opportunity to get the message about early detection across to some of those most at risk, and to persuade them to attend a free check-up.

“Most of our patients are people who drink and smoke a lot, and many are extremely poor,” she said. “Our dentists are good at referring patients with suspicious symptoms, but these people never go, partly because they can’t afford to, so they tend to be referred by their GPs when they have a lump in their neck.”

The best way to reach this target audience, she says, is through the media, or by “going into the streets”. In Porto and Lisbon, doctors, patients and volunteers handed out leaflets to people passing through subway stations, inviting them to attend a free screening day if they felt they had reason to be concerned.

The campaign was supported by articles on head and neck cancers in national and regional newspapers and radio and television interviews with leading doctors.

Two days later, 28 institutes across the country opened their doors to people who wanted to be screened, overwhelming some centres. Though precise figures are not yet in, Castro says that around 10% of those who attended were referred for further tests. Media interviews with some of the men and women who turned up to be screened reinforced the message about awareness of risk and symptoms and the importance of seeking medical advice.

Castro’s one regret is that most of the people who came to be screened were not smokers or drinkers, meaning they probably didn’t reach their target audience. “Next year we will think about actions for special groups, like taxi drivers or people who go out at night.”

Later the same week, Castro and her Make Sense team organised for doctors to visit two high schools in Porto and Lisbon, where they showed a cartoon. Rastreio do cancro da cabeça e pescoço, available on You Tube, tells the story of a typical young man who is into smoking, drinking and many girlfriends, exposing him to the three big risk factors (HPV infection from oral sex is estimated to account for almost one in three throat cancers). The young man changes his lifestyle after the death of his father from head and neck cancer.

The cartoon has had well over 2000 viewings. “The message is about moderation,” says Castro, and she believes it was very helpful in getting students to think about their own risk behaviour. An offer to screen students, she says, also led to a number of HPV-related lesions being picked up. She is now planning to organise similar sessions in other schools throughout the coming year.

Castro insists the results of this hard work were worth “every minute of it”, especially conducted as a pan-European event.

Standardising quality of care

The policy agenda was addressed with the launch of a White Paper at the European Parliament (makesensecampaign.eu/white-paper). This was a chance to show policy makers the devastating impact of head and neck cancers, and the need for high-quality care and rehabilitation. The White Paper highlighted the need to involve not only medical and radiation oncologists, head and neck surgeons, and radiologists, but also oncology nurses, speech therapists, social workers, psychologists, plastic and/or reconstructive surgeons and dentists specialised in these types of cancer.

It called on the European Commission to promote policies which ensure that all patients across Europe have access to care from specialised multidisciplinary teams – currently delivered as standard practice in only a handful of countries.

It also proposed that patient advocacy groups should be involved in providing assistance and support to patients, from diagnosis through to rehabilitation, as well as being involved in awareness campaigns, and providing updates on new treatments, research programmes and clinical trials.

Reaching out to health professionals

The final day of the awareness week reached out to healthcare professionals, with a meeting at the ECCO cancer conference, where delegates were invited to hear about Make Sense. In participating countries information about detection and best practice for care and rehabilitation was distributed to GPs, community dentists, pharmacists, maxillofacial specialists, ear/nose/throat doctors as well as all those directly involved in care and rehabilitation.

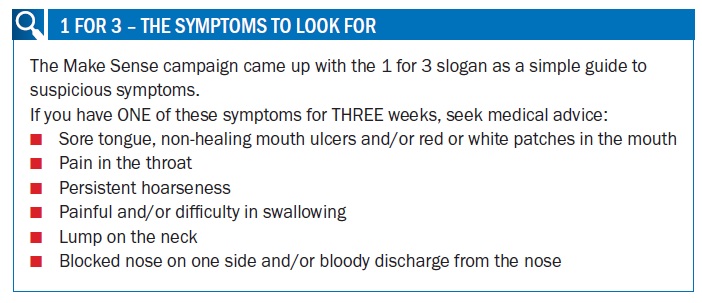

Wojciech Golusiński, head of the department of Head and Neck Surgery at the Greater Poland Cancer Centre in Poznań, was responsible for the professional education work of the Make Sense campaign. He is particularly proud of the “1 for 3” slogan (see box), which describes the symptoms that should prompt patients to get checked out, and alert professionals to refer patients for further examinations. “We selected the six main symptoms for head and neck cancers,” says Golusiński. “If you have any one of these symptoms for more than three weeks you should seek medical advice. It is very easy to understand, not just for the public but for healthcare professionals.”

In Poland, 150,000 leaflets were distributed in the 16 administrative regions, where each local Make Sense campaign was led jointly by a surgeon and a medical oncologist or radiotherapist.

In Poland, 150,000 leaflets were distributed in the 16 administrative regions, where each local Make Sense campaign was led jointly by a surgeon and a medical oncologist or radiotherapist.

Some of the best responses came from the nurses and medical students, who were eager to participate in the campaign. Dentists and GPs – key to early detection – were far less responsive. In Poland, says Golusiński, dentists accept no responsibility for the wider health of a patient, and most see their job purely as a way to earn a living. “They don’t examine the oral cavity, and they see themselves responsible for the teeth only.” GPs on the other hand don’t always have the necessary expertise, they don’t receive specialist training, and they deal with a lot of other problems. The result, says Golusiński, is that “they often spend months treating patients for dysphagia, hoarseness or other symptoms, while the neoplasm is rapidly growing.”

This problem cannot be resolved by a one-week campaign, he says. The next step must be to present Make Sense at all the national and international conferences of the GPs, dentists and other health professionals. Ultimately, he hopes to see the key information incorporated into curricula at medical, dentistry, pharmacy and nursing schools. He believes it will take at least two years of hard work to make real progress.

“GPs often spend months treating patients for hoarseness or other symptoms, while the neoplasm is rapidly growing”

A partnership with patients

Lisa Licitra, chief of the Head and Neck Cancer Medical Oncology Unit, at the Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori, Milan, agrees that Make Sense must be a long-term campaign. She has taken responsibility for developing a sustainable partnership with European patient advocacy groups, and believes that patients are very powerful. “It is really very impressive when you speak with a patient who has been rehabilitated, who has no voice, but just a stoma.”

In Italy active groups have taken on the task of helping people with voice rehabilitation, “which takes hours, and hours and hours, and is not always successful.” They are also lobbying on things like prostheses and medical benefits. However, across Europe, she has found patient advocacy groups to be “very dispersed and poorly coordinated.” Building a strong advocacy partnership will take time and negotiation, as some groups are wary of being expected to provide support and advocacy, without being given a say when it comes to key decisions that affect patients.

This is certainly the view of Henrike Korn, who founded the German Head and Neck Cancer Foundation (khts.org) after her husband died from tongue cancer. She has more reason than most to welcome the efforts of the Make Sense in educating health professionals on early detection. Her husband might be alive today if one of the five doctors he visited – including a GP, dentist, maxillofacital specialist, dermatologist and ear/nose/throat specialist – had recognised the gravity of any of the symptoms that she now knows to be typical of tongue cancer.

She also welcomes efforts to promote access to care by specialist multidisciplinary groups. Germany, she says, has been very slow to move towards this way of working, and as a consequence patients often find themselves on their own after leaving hospital. Henrike spends much of her spare time “substituting” for the role of outpatient nurse or case manager, helping patients who have no voice and don’t leave their homes.

Enablement and empowerment is what she feels patients value. “Give them the tools to be able to live alone, let the nurses go out and tell them how to deal with all these things they have at home, the tubes and everything, so they are enabled to get along with their illness without a nurse or physician as far as possible.”

Only when patient groups are given a say, for instance, in deciding the quality indicators by which head and neck centres are evaluated, will she see the relationship with professionals as a true partnership.

In Milan, Licitra agrees that patients must be given a say. “What the Make Sense campaign was trying to do was to put together a partnership between them and us, and ask them the direction we should take in this disease. I would also advocate that they should participate in research planning, because we know that there may be very different opinions in terms of outcome from research.”

These are early days for the campaign, and participants are thrilled it got off to such a good start. Golusiński describes the media response as “amazing”. “In Poland, like the rest of Europe, campaigns on head and neck cancers did not exist until now.” Licitra also sees it as a big step forward, “I’ve been in head and neck cancers for 25 years and I’ve not seen anything like this. It’s good to be part of a pan-European project.”

Leave a Reply