A new model for caring for depression in cancer patients shows how much can be achieved even on a tight budget.

That being diagnosed with cancer carries an increased risk of depression is perhaps not unexpected. What comes as a surprise to many people, however, is how effectively even major depression in cancer patients can be treated, provided it is done in the right way.

That being diagnosed with cancer carries an increased risk of depression is perhaps not unexpected. What comes as a surprise to many people, however, is how effectively even major depression in cancer patients can be treated, provided it is done in the right way.

This was demonstrated most recently with the results of a randomised controlled trial that showed impressive results for a new approach to treatment that integrates care for depression with the other aspects of the patient’s cancer care (Lancet 2014, 384:1099–1108).

The SMaRT Oncology-2 trial randomised 500 outpatients with cancer, diagnosed with major depression, to the new integrated “depression care for people with cancer” or to usual care.

Using a primary outcome measure of 50% or greater reduction in depression severity, scored on the self-rated Symptom Checklist Depression Scale SCL-20, almost two-thirds of patients (62%) randomised to the new approach responded to treatment.

This compared with a response rate of fewer than one in five (17%) of those randomised to the control arm. Treatment for these patients was left in the hands of the patient’s oncologist and general practitioner (GP), who were informed that their patient had been diganosed with major depression, and were asked to treat them as they normally would.

A smaller, parallel, randomised controlled trial – SMaRT Oncology-3 (Lancet Oncology 2014, 15:1168–76) – looked at the effectiveness of the same intervention specifically in cancer patients with a poor prognosis. It found a significantly better response among patients randomised to the integrated treatment, even in this more challenging group, using average depression severity over the patient’s time on the trial as the primary outcome measure.

The results are important because they show policy makers the value of including psycho-oncology within cancer services, and they challenge nihilistic attitudes about the potential for successfully treating depression in cancer patients.

“We have got rock solid evidence now, and believe this is the way forward in ensuring people with depression are treated effectively,” said Mike Sharpe, a professor of psychological medicine at the University of Oxford, and joint first author of the two studies.

Delivery of the treatment programme relies heavily on specialist cancer nurses, who are given intensive 12-week training in depression care for people with cancer. They work in a team with supervising consultation liaison psychiatrists, working in collaboration with the patient’s oncology team and GP.

The study authors attribute the success of the model to a number of factors. It was intensive – a combination of regularly reviewed drug treatment together with psychological therapy delivered in up to 10 sessions, mainly face-to-face, over a period of four months. The training and delivery was done systematically, with regular supervision of sessions using videorecordings, and regular monitoring of patient outcomes. And it was integrated with the patients’ cancer and primary care to promote acceptability and adherence.

They also draw attention to the surprisingly poor results in the control arm, where more than four out of five patients failed to respond to “usual care”.

A welcome approach

The principle of delivering psychological support as an integrated part of patient’s cancer care has wide support among the patient advocacy community. Europa Donna, the European Breast Cancer Coalition, has long been campaigning for all breast care to be delivered by certified specialist units or centres, with access to psycho-oncology services among the criteria for certification.

Stella Kyriakides, a former president of Europa Donna and a member of the House of Representatives in Cyprus, says: “It is vital that psycho-oncology is part of a multidisciplinary approach from day one,” but she recognises that for many patients this simply isn’t happening.

“It is true patients don’t get the help they need at the moment. Very few centres have this multidisciplinary approach and not all countries have units which allow for this type of care.” The situation for people with rarer types of cancer is far worse, she points out, as they are even less likely to be treated within a multidisciplinary team.

There are wider problems too, she argues, particularly in southern Europe, where mental health care is often seen as a luxury and is ignored. “It is not a luxury for patients, but a right,” says Kyriakides.

The German model

In some countries, such as Germany, integrated approaches similar to the one proposed in the SMaRT studies are already up and running. Guidelines published in January this year on diagnostic and treatment approaches recommend a three-step system, which involves screening, counselling and treatment.

Treatment can involve relaxation techniques or psycho-education where the distress is not severe, and psychotherapy combined with antidepressants or anti-anxiety pharmaceutical treatments in cases of severe depression. “If the patient is over the threshold then they are referred to see a psycho-oncologist. If they are under the threshold they will simply get basic information about their cancer,” explains Joachim Weis of Department of Psycho-oncology at Freiburg University.

The German system of psycho-oncological care, he says, is mostly based around psychology and psychotherapy. There are very few psychiatrists working in this field. More importantly, there is a big difference between inpatient and outpatient care. Most cancer patients are treated on an inpatient basis, within certified cancer centres, where integrated psychosocial care is obligatory.

Here patients may see a psycho-oncologist, psychotherapist, psychologist or even a social worker with further education in that field. The nurses in Germany, particularly those who are highly educated in psychosocial competency, are mostly engaged in screening rather than diagnosis.

Germany is unusual in offering cancer patients three weeks at one of the country’s 130 specialist rehabilitation centres after their last oncological treatment, where they have access to interdisciplinary teams including psycho-oncologists, social workers, physicians and nurses.

Around 30–40% of all German cancer patients choose these aftercare programmes, which provide high-quality care, says Weis. “During this period we often have a better opportunity to identify if they have a high level of psychosocial distress or psychiatric disorders… It is often in this early rehab phase where patients are identified as having depression or problems coping,” he says.

But like everywhere else, health budgets are being squeezed and reimbursement for psycho-oncology services is becoming an increasing issue. There are ongoing discussions with the insurance companies and the Ministry of Health to ensure that it can be paid separately, says Weis, because it is more than the basic budget allows.

“In Germany the focus of the medical system tends to be more on technical aspects, so there is never any problem finding money for high-tech equipment. Since the recession, however, we are struggling to get the money for psycho-oncology, because it comes quite low on the shopping list of cancer treatments.”

The European picture

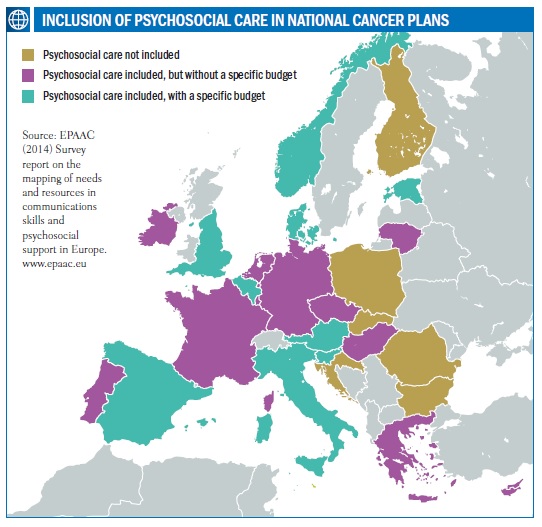

In other parts of Europe the picture is very different. A recent survey conducted by the International Psycho-Oncology Society IPOS, as part of the European Partnership for Action Against Cancer (EPAAC), mapped the needs and resources in communication skills and psychosocial care in 27 countries across Europe.

“Whilst many European countries have integrated psychosocial care into their national cancer plan it is clear there is still much to do in terms of allocating resources and delivering the care equitably,” says Luzia Travado, the newly elected head of IPOS.

Travado was a key player in developing the survey and believes there is still huge resistance to recognising mental health or distress as a major component of oncological care, despite intense national and international campaigns by professional organisations.

The slogan “distress is the sixth vital sign,” has been a focus of campaigns for better psychosocial care across Europe. IPOS has now enshrined in its International Standard of Quality Cancer Care the requirement that cancer services must integrate the psychosocial domain into routine care and that distress should be measured as the 6th vital sign after temperature, blood pressure, pulse, respiratory rate and pain.

“To improve patients’ outcomes it is necessary to integrate psycho-oncology into standard routine cancer care, from diagnosis, across treatment and all phases of disease and survivorship as a vital part of comprehensive high-quality cancer care,” says Travado.

Although 21 of the 27 countries in the EPAAC survey already have psychosocial services as part of their national cancer plan, only half of them actually have a budget for the treatment.

21 of the 27 countries include psychosocial services in their national cancer plan, but half have no budget for it

The survey threw up other barriers too. Many psychosocial services in Europe are only available in cancer centres, university hospitals and cancer rehabilitation centres and only rarely in general hospitals. Referrals to these services have been reported as inconsistent, and in some countries the availability of these services is still scarce or completely absent.

One consequence, says Travado, is that doctors feel more reluctant to tell their patients the truth about a cancer diagnosis. She cites Bulgaria, as an example: “Here where there are no psychosocial cancer care services available, doctors tend to be more silent about the diagnosis. Doctors have more confidence in disclosing a diagnosis to a patient where there is a psycho-oncology service in place to refer to.”

The EPAAC survey also showed that only 16 European countries have a national psycho-oncology society affiliated to IPOS, which may in part account for the lack of specialist professionals and low levels of interest in fostering psycho-oncology in those countries.

“There is a clear need for improving training and certification in psychosocial cancer care as well as developing a national policy which recommends the use of existing clinical guidelines,” says Travado.

In 2013 IPOS piloted training workshops in Romania as part of its EPAAC activities. These included demonstrations of best practice in communication skills and psychosocial care, using a stepped model that matches levels of interventions to different levels of need.

“There is a clear need for improving training and certification in psychosocial cancer care”

“We ran this programme nationally with the help of local government. We included training for the trainers, including psychologists and oncologists, who were then able to cascade this training into regional areas. We also invited nurses to participate, but their English was not good enough so we realised it was important to have Romanian people providing the training,” says Travado.

Funding psychosocial care

The worry is that pressure on health budgets is making it harder to secure the funding to ensure all cancer patients have access to the psychosocial services they need – or even to defend existing services, as in the case of Germany.

Aware of this problem, the team behind the SMaRT trials included an analysis of the cost of delivering the proposed integrated approach to treating depression in cancer patients, which came out at a surprisingly low £600 (750 euros) per patient.

Mike Sharpe, principal investigator, argues that this represents very good value for money. “If you don’t treat depression in cancer patients you get cancer care that is painful, hugely disruptive, expensive and people come out of that care and say, ‘I wish I had died.’ That can’t be a good outcome can it?” he says.

On top of the benefit to the patient’s quality of life, there could also be savings for the health service and the economy if better mental health helps patients engage more effectively with decisions about their care, adhere better to their treatment, and function better in terms of their work and family lives.

Certainly the proposed integrated care model has been warmly received by the Chief Medical Officer in England, and there is even talk of a pilot scheme starting at a large teaching hospital in London.

Whether other countries will be as keen to embrace such a model remains to be seen. Key to keeping the costs low is the prominent role given to specialist cancer nurses, who tend to be paid less than psychologists and psychiatrists. But many countries do not educate and train nurses for such specialist roles.

Kyriakides believes such a central role for nurses is a sensible way to go. “Nurses are at the frontline with cancer patients, not the oncologists, and it makes sense that they are part of any integrated approach to cancer care,” she says. “In the case of breast cancer in Cyprus and other parts of Europe, we already have breast cancer nurses and they are key to the emotional care of the patients. I think that nurses have already become such an important part in support and treatment in many areas of health including mental health. A well-trained nurse would make a huge difference to cancer patients, and I do think it would translate to Europe,” she said.

Securing funding for this type of care to be delivered across cancer services will, however, require taking the argument to policy makers, particularly in countries that currently have no budget at all for psychosocial services.

“Surely we are all agreed in 2014 that people’s outcomes should not be measured just by length of life but also by quality of life. So it seems quite obvious to switch some of the budget from prolonging life to making life more tolerable,” says Sharpe.

“It seems quite obvious to switch some of the budget from prolonging life to making life more tolerable”

Travado agrees. “We need to make a case to the politicians that it is more worthwhile to them to have better adjusted citizens that are survivors of cancer than just not pay attention to their needs. When you introduce a psycho-oncological dimension to a patient’s care you actually reduce costs, because fewer people drop out of work as a result of their psychological suffering,” she says.

But it’s not just policy makers who need convincing, says Sharpe. Introducing this integrated approach to care will also require cancer professionals who want to pick up the idea and run with it, and are willing to change their practices and champion new ways of working. Travado agrees. “We cannot simply parachute into other countries in Europe with new ideas without having champions on the ground there who are willing to drive it forward,” she says.