Patients look for the best treatment centres, says this leading voice in European urology. So theyll go where the specialists involved in their care work together, not where they are constantly battling over who is in charge.

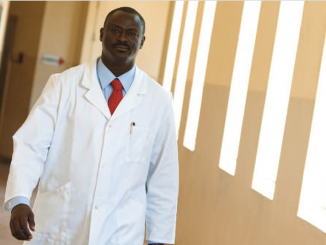

Per-Anders Abrahamsson is too modest to claim that, over his 11 years as Secretary General of the European Association of Urology (three as adjunct), he has succeeded in establishing urology as a specialty in Europe. That was certainly his aim, he says.

Per-Anders Abrahamsson is too modest to claim that, over his 11 years as Secretary General of the European Association of Urology (three as adjunct), he has succeeded in establishing urology as a specialty in Europe. That was certainly his aim, he says.

But the numbers tell a story. The EAU now has 17,000 members and the number of urologists attending the EAU’s annual congress has risen threefold, to 15,000, representing all European countries. Its members now come from not just Europe, but Latin America, Oceania and South East Asia. Its journal now has the top impact factor in the field of urology and nephrology.

Abrahamsson has also been responsible for collaborative cancer initiatives – for example setting up an annual European Multidisciplinary Meeting on Urological Cancers with the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) and the European Society for Radiotherapy and Oncology (ESTRO). He has been an influential researcher and opinion leader in prostate cancer.

But the territorial disputes of the cancer world have never been far away. When I meet him in Malmö – the bleak but hypnotising industrial city in southern Sweden that formed the setting for Stieg Larsson’s novels and hit TV drama ‘The Bridge’ – the politics of cancer is much on Abrahamsson’s mind.

He is quick to point out to me – as he has many times to European politicians – that urological cancers (including prostate, kidney, bladder, testicular and penile cancers) together constitute one-third of all cancers. In a world of scarce resources and scarcer attention spans, every form of cancer must make its case for primacy.

And when I start our interview in his office at Skåne University Hospital by asking him what he’d like to talk about, he tells me that he has just returned from a meeting of the European Cancer Organisation (ECCO) in Brussels, and is worried about ESMO’s recent decision to hold its own congress every year rather than continuing to collaborate with ECCO on the organisation of the biennial European Cancer Congress.

“We have to work as a team,” says Abrahamsson, who is Professor of Urology at Lund University and Chairman of the urology department at Skåne. “It has been a major task for me at EAU to try and help bring all the people in cancer under the same roof.”

For Abrahamsson, building a strong ECCO and getting all disciplines to work together in the interests of patients are synonymous. But the cause is made more difficult by tensions created by the increasing role of organ-specific specialties in cancer.

Turf wars between medical oncologists and urologists are a particular source of vexation for Abrahamsson. In some European countries, urologists – normally surgeons by training – play the central role in treating urological cancers, even though more and more specialise in oncology. Many see little benefit in handing control of cancer patients to medical oncologists who have less knowledge of, say, the prostate. Medical oncologists, they say, should be brought in at their request rather than co-ordinating care.

So although “working together” is an Abrahamsson mantra, achieving it in urological cancer has been fraught with difficulty in Europe. “In some countries, there is a major battle,” he says.

“In Germany for example urologists are pretty well handling everything including chemotherapy, and they are not much working together with medical oncologists,” he says, adding that there are urologists within EAU who want to be independent of all other specialties – not just medical oncology but areas such as imaging too. But Abrahamsson is adamant that this is not the way forward. “It’s not going to happen,” he says. “You cannot do everything.”

“We organ specialists have to work closely with all the other specialties involved in cancer – imaging people, radiation oncologists, medical oncologists, basic researchers, nurses – which is why I think the multidisciplinary outlook of ECCO is so important,” he says. He asserts that most urologists within the EU are indeed working in a multidisciplinary fashion. “It is the only way forward, because it is what patients want.”

“It is clear that surgery cannot cure everything. In urological cancers, it’s all about using adjuvant and neoadjuvant radiation, and in some cases, such as testicular cancer, chemotherapy. I remember a medical student on my course dying of testicular cancer in the 1970s, but now in Norway and Sweden we cure 99% of our testicular cancer patients. This is a wonderful example of why we need to work together, and I cannot understand this on-going fight between different organisations.”

The last four years of Abrahamsson’s term as Secretary General, which came to an end in March, has seen him turn his attention more and more to politics, and he jokes that his next role will be Secretary General of the United Nations. But he is hopeful the battles will end soon.

“There are dinosaurs fighting to maintain what they have on both sides, but I’m optimistic that within five years it will be history.Patient organisations like Europa Uomo are getting better organised and asking for everyone to work as a team, and we have asked politicians in Brussels to look at the same thing.”

“There are dinosaurs fighting to maintain what they have on both sides, but I’m optimistic that it will soon be history”

Abrahamsson doesn’t have much time for dinosaurs, hierarchies or those who insist on being named as ‘in charge’. He is from the Scandinavian school of open-necked informality, and proudly explains that everyone he works with at his hospital and the EAU headquarters in Arnhem, in the Netherlands, calls him Per-Anders – or even Papa Pelle, a family nickname that somehow spread. When he took over as EAU Secretary General in 2007, he changed its military-style top-down management model to a more level, consensual structure, with four team leaders who he “trusts with everything”. It was based on the structures at his own hospital. “It’s more time consuming, but I totally believe in it because it’s about mutual trust.”

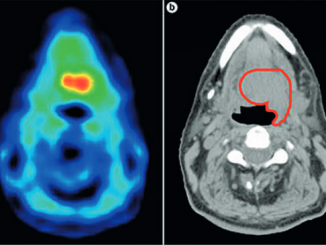

So consensual working in urological cancer makes total sense to him. And in the field of prostate cancer, it extends to supporting the spread of specialist multidisciplinary prostate cancer units – along the lines already well established for breast cancer. In 2011, the European School of Oncology promoted the concept of prostate cancer units in an article in the European Journal of Cancer, and set out what was involved in terms of professional education and experience. The concept revolves around two principles: every surgeon and radiotherapist who treats patients with prostate cancer must specialise in the disease; and volume equates to quality.

EAU met with ESO to discuss prostate cancer units at the EMUC meeting in Lisbon last November. “We are working together on this, and I am convinced we will sign a partnership with ESO because we have the same goals. We are definitely behind the concept of units. In many countries already, for example the UK, you now have to operate a certain number of cases a year and demonstrate follow-up and outcome to be allowed to carry out a procedure. I am convinced this is what will happen in all European countries, but it will take some time. In Germany, for example, you currently have at least 120 centres carrying out radical prostatectomy, which is not acceptable.

“If you don’t have on hand a whole range of other people – including qualified pathologists, imaging people, specialised nurses, and those who can help with the side effects of treatment such as incontinence – you shouldn’t be allowed to perform surgical procedures.”

Again, it is pressure from patients for evidence of good outcomes that will be the main force for creating centres of excellence. “Of course they are heading for the best centres, and that’s going to happen in Scandinavia, as well as the UK. That’s why, in centres like our own, we are working like brothers and sisters with other disciplines.”

Research into prostate cancer has been a central plank of Abrahamsson’s career, continuing alongside his work as clinician and teacher. His innovative research in the 1980s and early 1990s identified new kinds of prostate cancer neuro-endocrine cells and the peptides produced by them, and these were subsequently identified as promoting progression in some types of aggressive cancer. Today, there is increasing interest in neuroendocrine differentiation as a marker for prostate cancer aggression.

But it might never have happened if he’d been faster on his feet. Born in 1949, the son of a farmer and a nurse, he knew from his teens that he wasn’t going to take over the family farm by the Baltic Sea, 150 km north east of Malmö. He was determined to be a Swedish version of German footballer Franz Beckenbauer, and played for a Swedish second division team. He had good ball skills and was a good header of the ball – and even today, he would be a commanding presence on a football field.

But he soon realised he wasn’t fast enough to reach the top level. Influenced by his mother’s vocation, he decided to enter medicine. He started medical school at Lund University, just north of Malmö, in 1970, and then in 1977 started training as a resident surgeon at a small hospital in Trelleborg on Sweden’s southern tip.

Under the guidance of Arne Weiber, then President of the Swedish Society of Surgery and “a living legend” in Swedish medical circles according to Abrahamsson, he gained experience of every-thing from neurosurgery to delivering babies.

Work at Trelleborg also allowed him to pursue his obsession with football. He became team doctor for Trelleborg’s football team – then in the Swedish third division – and stayed with them as the part-timers rose to the first division and then in 1994 defeated the British champions, Blackburn Rovers, in the UEFA Cup. He is a board member for the club, was appointed President in 2003, and is still completely obsessed: a team shirt hangs framed outside his hospital office.

But in 1980 he decided he wanted to be a urologist, not a general surgeon, and he began another residency, this time at Malmö University Hospital.

“At that time I had no clue about the technologies and new surgical techniques that would transform my specialty,” says Abrahamsson. “In the early ’80s, we couldn’t have imagined performing shockwave or laser lithotripsy for kidney stones, and we wouldn’t have dreamed about performing radical prostatectomy to cure prostate cancer. We were using oestrogens for disseminated disease, and if you were diagnosed with penile cancer it was simply amputated.”

It was the urology chief at Malmö, Lars Wadström, who gave Abrahamsson the ambition to enter research, and it was his own doctoral thesis, completed in 1988, that established Abrahamsson’s work on prostate neuroendocrine cells. On the basis of that, he was invited to the urology department at Rochester Medical Center in New York, becoming its laboratory director in 1991 and adjunct professor in 1993.

During his three years there, he brought in molecular biologists from all over the world, finalised 45 papers and – thanks to the influence of the department chief Abraham T K Cockett – made wide contacts in the urology world. Since then, Abrahamsson has become known for his skills as an international networker.

Returning to Malmö, however, he became dissatisfied that he could not get an appointment as a departmental chief, so began using his networking skills and giving talks about his research. At a talk in London in 1995, he met Frans Debruyne, then Secretary General of the EAU, who told him: “You are going to be Secretary General one day.” Shortly after, he was asked to become a member of the scientific committee – and that is how his involvement with EAU began.

In 1998 he became chairman of the urology department at Malmö and Lund university hospitals, and then full Professor of Urology at Lund University in 2000. The two university hospitals have now merged, into Skåne University Hospital. “Now we are no longer competing against each other and we can cover all fields of expertise.”

After 20 years, he is due to step down as urology chief later this year. His perspectives on the challenges of the past and the opportunities ahead have been moulded over 40 years of clinical, research, management and political experience.

In the field of prostate cancer, perhaps most striking is his view that universal screening for prostate cancer is a realistic possibility – based on taking early and, if necessary, repeated PSA readings, but not normally intervening quickly with biopsies or surgery if raised levels are found (as has become the norm).

His view is founded in research from his own department, using stored blood serum samples from 20,000 men aged 35 to 45, 900 of whom were later diagnosed with prostate cancer at the hospital. Detailed analysis indicated that low PSA levels at age 45 indicated a very low risk of prostate cancer, but levels higher than 1.5 brought increased risk later in life.

“It shows clearly that you should have a baseline reading taken when you are fairly young. If it is low, then you can wait five years before you have it again. If it is higher, you have more tests on a more regular basis,” says Abrahamsson. An international randomised trial with 18 years follow-up, being coordinated from Erasmus Medical Centre, Rotterdam (the European Randomised study of Screening for Prostate Cancer or ERSPC) indicates that such procedures reduce the chance of dying from prostate cancer by up to 50% – “that’s more than any breast cancer screening study has shown.”

Those wary of PSA testing say that it is an inaccurate indicator of prostate cancer, and that raised readings are often the result of other conditions or indolent tumours. It can lead to unnecessary anxiety, harmful biopsies, and unnecessary treatment, leading to incontinence and impotence. Supporters say it should be used widely because it is a better cancer marker than we have for any other type of cancer and can lead to life-saving early interventions.

Abrahamsson straddles the two camps. He wants national screening programmes that use PSA tests in a more considered way, alongside active surveillance. But he acknowledges this will require a change in attitudes to test results among clinical staff, as well as patients.

He wants national screening programmes that use PSA tests in a more considered way, alongside active surveillance

There’s a danger that, as soon as a PSA result presents a red flag, everything starts. The patient gets scared and things move very quickly. We don’t want that to happen, so you need to educate patients, relatives, healthcare providers on how to proceed in a considered way. That will take time, and we cannot introduce mass screening programmes straight away. But eventually, in the future, I am convinced that testing decisions will be made on the basis of a PSA test in your 40s – unless, of course, you have a family history, in which case the need for regular testing is clear.”

Abrahamsson is waiting for more results from the European randomised trials before taking the idea to policy makers. But he is about to present an award lecture on the subject at the American Urological Association meeting in New Orleans this May. The response will be interesting, given the fact that American doctors have a long history of responding to an early diagnosis of cancer with surgery rather than active surveillance.

In terms of treatments for prostate cancer, Abrahamsson has mixed feelings about the progress made. Remembering the “bloody mess” of radical prostatectomy when introduced into Sweden in 1987, he marvels at the precision of the Da Vinci robots on which surgeons today perform 500 prostatectomies a year in Malmö – and the resultant reduction in incontinence and impotence.

But for all the technological advances, progress in prostate cancer treatment is still slowed by some basic and gaping holes in research.

“Those treating prostate cancer always have the problem that there is no randomised trial comparing radiation therapy with surgery. But we have started one here in the department, genuinely randomising patients to radiation or radical prostatectomy. It has to be done. Generally, around the world, people look to Scandinavia for the best randomised trials, the landmark studies – because of our health system, but also because our patients are historically more willing to be randomised. It’s almost impossible to randomise patients in the United States.”

Abrahamsson won’t contemplate complete retirement. He will continue as a clinician at the hospital, and is hopeful that new-found time will allow him to pursue new research. He wants to investigate the stem-cell characteristics of cancer cells, test new combinations of treatments including chemotherapy, and find better ways of identifying the most aggressive cancers and tailoring treatments to them. His team has already begun the stem cell work in collaboration with Norman Maitland, Director of York University’s Cancer Research Unit in the UK, and Jack Schalken, Director of Urology Research at Radboud University Medical Centre, the Netherlands.

But he’s wondering how he’s going to cope without travelling. His role with EAU takes him tens of thousands of miles each year, and he wonders whether he might be addicted to travel. He started establishing international links early in his career, traveling to Poland on several medical relief missions during martial law and the economic crisis in the 1980s (he was awarded a Red Cross medal for his work). Since then, he has travelled regularly to central and eastern European countries to give lectures – not just Poland but Russia, Serbia, Ukraine and Romania. He has been awarded honorary professorships in most of these countries.

“I probably spent more time in these countries than some western European countries, because they wanted to catch up. It also helps that I speak Russian. But I’m always curious and I have been traveling like crazy. But I haven’t seen all the countries in the world. I haven’t been to Moldova!”

He got engaged to his Swedish wife – a nurse he met while teaching at a nursing school during his medical training – when they were on their first Polish relief mission together. “She has supported me all the way.” Their three boys used to tell him as children that he worked too much and didn’t earn enough money. One became an international lawyer, presently in Shanghai, China, another went into IT in Spain. And the other became a Swedish urologist. Abrahamsson keeps in touch with them on Skype, and there’s a big screen on the wall in his office for their conversations. But twice a year, the families still get together for a week in the Swedish archipelago, sailing a Nordic ‘Folk’ boat, and skiing in the Alps.

“The only real challenge in my career has been lack of time,” he says. “Now, I think, if there’s anything I could do in the next few years, it would be to continue to work in the international arena and offer them my experience and networks – I know so many opinion leaders in urology and oncology.”

“There are too many super-egos among doctors, politicians, CEOs. You find them everywhere”

And it’s here that he may need to take on the role of a United Nations-style peacemaker. “Time is so short, it’s crazy. There are too many super-egos among doctors, politicians, CEOs. You find them everywhere. They have to downsize their egos. We need to sit down peacefully together, not fight each other.”