When we talk about advances in cancer care patient advocacy groups tend to focus on the development of new drugs, immunotherapy being the latest flavour. This is encouraged by the pharma industry, keen to gain traction for new treatments wherever it can. It means that we find it easy to overlook the arrival of new technology in other areas of treating cancer and the benefits that these developments can create for patients.

As someone who has had more than 20 CT scans and 6 MRI scans this is an obvious place for me to start. My first CT when I was diagnosed in 1999 was chest/abdomen/thorax. I recall several “take a deep breath and hold your breath” moments. That same diagnostic scan done today takes less than five seconds. Similarly with MRI. Not only has the speed increased but the level of image detail has improved immensely and the techniques of analysis which radiologists can employ have been extended and enhanced.

IT developments mean that x-rays and scans are on my oncologist’s desktop screen before I have left the radiography department. The full radiology report may not be available for a few more days but any ‘red light’ signs can be spotted immediately.

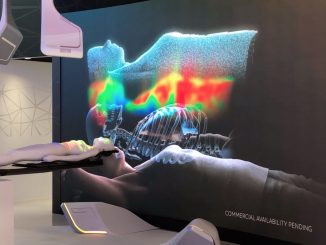

The changes in radiotherapy have been even more dramatic. From a single simple beam, to a shapable beam, to beams which conform to complex shapes, to tighter focus and intensity modulation. Couple imaging within the therapy control system and we now have SABR – stereotactic ablative radiotherapy – and its various versions. This has taken radiotherapy into new potential as an effective first-line therapy in some situations which could only previously be addressed by systemic approaches or by complex surgery with greater morbidity.

Ablative therapies use other technologies as well. Laser, radio frequency and microwave are now in relatively general use by interventional radiologists. Metastatic tumours in particular can be very effectively treated in liver and lung. Because the techniques are minimally invasive hospital stays are significantly lower than for traditional surgery and the nature of the technology makes access to them by older patients easier.

Lasers are also more widely used in surgery correcting eye defects, removing skin tumours and colon polyps for example. They are also used to stimulate drug activity in PDT (photo-dynamic therapy) using anti-cancer drugs which are responsive to light. The surgeon who operated on my lung metastases in 2013 used a laser-knife which offered the advantages of greater accuracy, shorter anaesthetic time and faster recovery, as well as automatic cauterisation of severed blood vessels.

Isolated limb perfusion (ILP) can be used on limbs with large sarcomas or melanomas, with the aim of avoiding the need for an amputation. The blood system in the limb is isolated from the body and extremely toxic drugs circulated around the limb. A radio-marker is inserted so that any danger of leakage into the body can be quickly detected. Tumours can be completely destroyed and surgery simplified. ILP is also being developed to use viral therapies, delivering them accurately to a localised tumour.

Other new technologies are appearing. HIFU (High Intensity Focussed Ultrasound) is very good with some single tumours, although less suitable for more widespread situations. Proton beam therapy has been treating eye tumours for some time and now high power proton beam systems are opening at many European centres. These are big systems and large investments, but at the same time nano-particles are arriving, with the ability to carry drugs accurately to a tumour while protecting healthy tissue.

Understanding all these technologies is a challenge for patient advocacy groups which advise patients. It is true that any single patient may only need to understand a small number of them at any one time but an advice-giver will need to know what might be applicable for any patient they are supporting and know where it may be available to them. These technologies are not everywhere yet and for some the clinical trial evidence of efficacy, especially long-term outcomes, is slow in coming. The fine detail of clinical techniques can take time to evolve and in some cases randomised controlled studies are not possible. This can make healthcare systems slow to respond to their potential. We can be certain that other technologies are also appearing, its just that I have not got to hear of them yet, further evidence of the problem.

For a patient advocate this area is a challenge but it should not mean that because it is easier to focus on drugs that is all we should do.