Should regulators insist on robust evidence that a new drug shows clear benefit to patients as a condition of approval, or are demands for such levels of certainty unrealistic, or even unethical? Marc Beishon reports on how ESMO’s new scale for scoring clinical benefit has added a new dimension to this long-running debate.

About 10 years ago, oncologists were confidently predicting that, by now, we would have a large portfolio of highly effective targeted drugs against cancer that would be the equal of the ones that kicked off the excitement – namely trastuzumab (Herceptin) and imatinib (Glivec). But that mostly hasn’t happened – although the latest immunotherapy checkpoint inhibitors are now being seen in this class.

There are just not many new cancer drugs that qualify as real game changers, particularly for solid tumours, although some are certainly huge money spinners for the pharmaceutical companies, owing to eye-watering price-tags.

There are though many recently approved cancer drugs, with more in the pipeline, and, while much has been said over the past few years about lack of effectiveness of many of the agents, we seem now to be reaching a tipping point. Certain oncologists are calling for at least a searching appraisal of the current regulatory model, which they say is sending too many agents of questionable value onto the markets of countries with hard-pressed health systems – and that now includes nearly all countries.

Meanwhile two of the world’s major cancer societies – ESMO in Europe and ASCO in the US – have launched tools to help oncologists to determine the ‘real world’ clinical value of cancer drugs. By providing scores for agents based in particular on overall survival (OS) and quality of life (QoL), it is hoped that health technology assessment (HTA) authorities, and also oncologists and patients, will be able to make better decisions about value and prescribing options – although offering value for money does not in itself mean that a drug is affordable.

ASCO has also launched Cancer-LinQ, a ‘big data’ initiative that is gathering information from oncology centres about the treatments they are providing, to feed into the picture of clinical value in patients seen in everyday practice – as opposed to those selected for clinical trials. There has also been a pipeline of papers and commentary about the shortcomings of the drug development process and the clinical trial system, with emphasis on highly costly phase III randomised controlled trials (RCTs) – often applied to a large population with little discrimination – and attendant issues such as regulatory burden, the declining proportion of research driven by academia versus pharma, and more generally the changing nature of cancer research, as drugs are targeted towards smaller ‘personalised’ groups.

In the middle of this highly complex debate is the regulator, principally the EMA in Europe and the FDA in the US. The regulatory system has been singled out as ‘broken’ by one high-profile commentator, Vinay Prasad, assistant professor of medicine at Oregon Health and Science University, who among his writing argued in the British Medical Journal last October that, at some point in the lifecycle of a cancer drug there needs to be demonstration of improved OS or QoL, if these were not demonstrated in the principal trials (BMJ 2017, 359:j4528).

Some say this should be before marketing authorisation by the regulator, others when surrogate measures turn out later to show benefit. But as Prasad says, the answer should not be ‘never’ – a point he makes by citing two studies from the US and Europe that show that a majority of drugs enter the market without showing OS or QoL, and only about 15% of these have since done so. It’s evidence, he says, of the breakdown in the regulatory system.

The study from Europe, published in the BMJ (BMJ 2017, 359:j4530), was picked up by the mainstream media, fuelling the debate about the cost and value of new cancer drugs. It used ESMO’s Magnitude of Clinical Benefit Scale (MCBS) to highlight that a majority of recently introduced agents fall well short of the highest levels of benefit. Other studies have shown no relationship between price and clinical benefit of FDA-approved drugs, and only 9 of 47 indications provided by the England’s Cancer Drugs Fund scored highly using MCBS.

“A majority of drugs enter the market without showing

OS or QoL, and only about 15% of these have since done so”

For Ian Tannock, another medical oncologist known for commentary on the cancer drug lifecycle, MCBS is a good example of a tool that could be used to improve the regulatory process – and in so doing could lead to drugs not being approved that otherwise would be. “Indeed, I am saying that certain drugs should not have been given marketing authorisation. I have no problem about approving a drug with a surrogate endpoint, provided there is follow up to show it helps patients live longer or better. But that isn’t happening with enough drugs. Even one that was withdrawn by the FDA, bevacizumab [Avastin] for breast cancer, is still in the NCCN [National Comprehensive Cancer Network] guidelines in the US. Approving drugs that do virtually nothing is very bad for patients and health systems. There must be connections with value and cost at the regulatory stage.”

A recent and “ridiculous” example, he says, is FDA approval for using adjuvant sunitinib for renal cancer. “Of the two trials, a larger one of 2,000 or so patients was totally negative, and a smaller one of 600 was only positive for progression-free survival but not for overall survival, and it has substantial toxicity.” There is a big difference between results such as this and those for clearly efficacious drugs, he notes, mentioning abiraterone for prostate cancer and the immunotherapy drugs for melanoma. Plots of the survival curves tell the story – those with little value show no significant overall survival benefit over time compared with the control, while effective drugs tend to show either a significant separation or no initial survival differences, but then a ‘tail’ for a small number of patients showing large effect.

“We do have some great new drugs,” says Tannock. “But I am concerned for patients who have little idea how to judge which ones are effective and end up selling everything to get them.”

He argues that the progression-free survival (PFS) findings from trials may be biased, citing the BOLERO-2 trial, which showed that adding everolimus – an mTOR inhibitor – to exemestane, doubled PFS in patients with advanced HER2+ breast cancer. “But toxicity was such that 25% of patients left the trial – and while the PFS was impressive, longer-term survival was negative. If you have an agent that improves PFS with minimal toxicity, such as aromatase inhibitors, that’s fine, but for those with high toxicity such as everolimus or sunitinib it is misguided to approve them.”

Tannock also notes that studies show a clinic that has run a trial and seen modest PFS can then see overall harm using the same drug in clinical practice on a mixed patient group that includes patients with comorbidities.

“I have no problem approving a drug with a surrogate endpoint,

if there is follow up to show it helps patients live longer or better”

In a commentary entitled ‘Relevance of randomised controlled trials in oncology’, Tannock and colleagues say the design and reporting of many RCTs can render their results of little relevance to clinical practice, and they argue that the bar for demonstrating clinical benefit should be raised for drug registration (Lancet Oncol 2016, 17(12):e560-e567). He feels that it should not be necessary to enrol thousands of patients to detect statistical significance if the drug is really of benefit compared with risk – and that using a certain ‘P-value’ to prove a hypothesis is a misreading of the statistical process – as the American Statistical Society has itself been at pains to point out.

Tannock is not going as far as to call the regulatory system broken, but says it needs to be revised. He argues that the EMA and FDA are too constrained by their current remit.

We’re doing our job, say regulators

Francesco Pignatti, head of oncology at the EMA, rejects the idea that the methodology they use for risk–benefit assessment is flawed or has too low a threshold for approval. “I do not think regulators need to change their regulatory value judgements about benefits and risks. But when we are recommending a conditional approval to bring early access to a drug for patients, there are uncertainties. We can sometimes assume that what looks like a remarkably high response rate will translate into a significant effect on OS, but this is still an assumption. We have the legal tools to take these uncertainties into account, but it needs to be understood that the expected benefits may not materialise. It does not mean the net risk–benefit is negative and that we should not have approved the drug, as there may be good reasons why such benefits are difficult to observe, or because there are other types of benefits, such as controlling the disease and associated symptoms for longer.

“That we are over-reliant on statistical significance is a myth. In our reports we go far beyond a tick box approach to approvals, carefully weighing all sources of evidence. But I believe that in specific situations there is room for patients’ choices and preferences about drugs, even if they may have a relatively low probability of success, and that our approvals should not be influenced by cost. We are constantly criticised for approving too many or too few drugs, but healthcare systems are stretched by cost – that should be the focus, not the regulatory threshold. If drugs were cheaper we wouldn’t be talking so much about it.”

Pignatti took the unusual step of responding to the BMJ paper – among his points are that OS can be hard to detect when patients switch to the test drug in an RCT, or when subsequent lines of drugs are used; and that, in specific situations, PFS is a valid efficacy endpoint.

He also defended single-arm trials, saying that in some cases they are justified as evidence instead of RCTs, and argued that QoL is often hard to measure. “It just is not the case that the only way to show that a drug has benefits is to show a significant improvement in OS – in certain cases doctors have for years been convinced by other types of evidence such as high response rates and response duration, or long time to progression of the disease,” he says.

“Healthcare systems are stretched by cost. That should be the focus, not the regulatory threshold”

Of course, some cancer drugs are rejected by the EMA owing mostly to lack of efficacy from RCT evidence: “When I last looked it was about one in four,” says Pignatti, adding that it is important for the regulator to help improve the drug lifecycle at both ends. He mentions refining tools for studying drugs for rare cancers, where a single-arm study may be the only option, and taking into account other research such as real world observational studies. Closer collaboration with HTA organisations to build an understanding of real world effectiveness is also underway, and national HTA organisations are also advancing in European harmonisation among themselves.

Pignatti points out that the EMA has been transparent in guidelines and reports in discussing the scientific and organisational issues involved in, say, early access to cancer drugs and the challenges of setting thresholds for new agents, and how careful planning of development and study design can help regulatory and post-marketing follow up.

It is critical, he stresses, that all actors in the drug lifecycle have clarity about what the objectives, roles and boundaries are, and that there is transparent debate about these issues, as the picture is getting yet more complex – and costly – with treatments such as CAR-T cell immunotherapy on the horizon. “We make complex decisions and choices in other fields, such as education, all the time with stakeholders that have different objectives that are sometimes conflicting. Healthcare is no different,” he says.

Markus Hartmann, a consultant who works with both pharma and academic clinical researchers, argues regulators are right to approve drugs even if the benefit–risk equation is small. He says that oncology is multimodal and proceeding in a multitude of small steps, and it is interdisciplinary action that mostly makes the best steps. “We also have much better understanding of genetic oncology and the subtypes in cancers – it may seem we have a lot of drugs approved for some cancers, but do we in fact have enough to get the best response rate across the subtypes?”

He agrees, however, that the current system is not sustainable, “…where we see countries such as some in Eastern Europe that cannot afford to give drugs such as the new immunotherapies, and in the UK up to 40% of approved novel drugs are not making the final step on their way towards clinical routine use.”

But he argues that high drug prices are in part the result of the high costs of meeting regulatory demands, which he says used to be far less stringent in the days when most clinical trials were run by cooperative groups rather than commercial enterprises.

He sees regulatory moves towards greater use of conditional and accelerated licensing – and more recently adaptive licensing – which allow phased approval through what the FDA calls “progressive reduction of uncertainty”, as signs of a rollback.

Is initial uncertainty really being reduced?

Adaptive licensing has though come under fire, again in the BMJ, where authors say that it “seems to be poised to weaken many of the regulatory changes that thalidomide produced”, and “phase II studies do not provide enough data to make good decisions about efficacy and safety; post-marketing studies are often delayed for prolonged periods and even when these studies are done regulatory authorities are slow to act on negative evidence; reliance on real world data is not a substitute for well-done RCTs; and once drugs are on the market abandoning them is extremely difficult” (BMJ 2016, 354:i4437).

In a short paper in 2017, Pignatti and colleagues recognise the challenges in designing confirmatory studies that follow on from approval and could offer HTA agencies some of the information they need to make decisions (Clin Pharmacol Ther 2017, 101:577–9). “We as regulators too rarely meet well-planned, well-powered, and well-executed exploratory studies.” By this they mean studies that complement the usual data on exposure/adverse events/tumour response with, for example, “use of functional imaging and tumour and liquid biopsies, with the aim of stratifying drug development, and an early confirmatory approach with respect to predictors of patient benefit.”

They also mention defining factors for resistance and tumour heterogeneity after treatment and, on immunotherapy checkpoint inhibitors specifically, they say that it has been “futile” to expect cooperation among companies in developing candidate assays. They even suggest that a “payers’ cooperative” in the EU to investigate cost-effective combinations in immune-oncology may be feasible.

This could also feed into efficient mechanisms of withdrawing ineffective drugs from the market, which Hartmann agrees is needed as a balance. “If we have that, we can take more risks, and it could also cut prices.”

Indeed, it is the rigour of post-marketing surveillance and regulation that seems to be the major concern of oncologists such as Tannock and Prasad, as they do recognise that surrogate measures are valid means of approving some drugs.

ESMO’s clinical benefit scale

This is also where ESMO’s Magnitude of Clinical Benefit Scale comes in (one of a number of tools for measuring clinical benefit of cancer drugs – the other main one being ASCO’s Value Framework). Elisabeth de Vries, a Dutch medical oncologist and chair of ESMO’s MCBS working group, says the scale was developed to address decision making in accessing relevant drugs, especially given limited budgets in certain European countries. “Not everyone was excited about this initially – the outside world was not sure what would happen if oncologists grade drugs and whether it would be good for patients,” she comments. But she says it has received largely favourable attention, as most countries have affordability problems.

“The scale’s methodology is transparent and anyone can use it to grade cancer drugs”

The scale relies on data from the clinical trials that led to drug approval, and can take into account a range of factors – OS/PFS, hazard ratio, long-term survival, response rate, prognosis, QoL and toxicity. Serious toxicity can downgrade the score, but fewer effects that bother patients can upgrade it. As de Vries says, it is unrealistic to expect all medical oncologists to be on top of the latest papers on all new drugs, so scores from MCBS give them a way to synthesise information for decision making (and Tannock praises the scale as being easy to use).

It is also the case, she adds, if there is additional data from subsequent publications regarding a given drug – on quality of life or on side effects, for example – the drug is graded again. ESMO is sufficiently confident with field testing to now incorporate the grades into its guidelines, but so far these only include drugs approved since 2016. New data can then mean drug scores can be up- or downgraded.

De Vries says there are misunderstandings about the scale. For example, in the BMJ paper that turned the spotlight on approvals (and which used the MCBS to score 48 drugs the EMA approved between 2009 to 2013), she and colleagues say in a reply that it is incorrect to say that the MCBS sets a “threshold for clinical meaningfulness”, and that only the highest scores matter (these are grades A and B for treatments of curative intent and 4 and 5 for non-curative). They point out that those with a grade 3 score are mostly approved for example by the Israeli HTA body, but those below mostly not. She adds that what is clinically meaningful also depends on the oncologist and patient. “Three more months may be extremely valuable if you want to see your first grandchild or to attend your daughter’s wedding.”

ESMO is in discussion about the MCBS with the HTA agencies in Germany and France, to see how it can be used in their healthcare systems. Countries outside Europe, including India (for its National Cancer Grid), are also considering adopting the scale, says de Vries. The European Hematology Association is currently testing the MCBS in the non-solid tumour field. As she adds, the scale’s methodology is transparent and anyone can use it to grade cancer drugs, while current HTA methodologies tend to be more proprietary.

Could pharma use tools such as MCBS to improve drug development? “We hope it will lead to more relevant clinical trials,” says de Vries. An example, although investigator-driven, is the SONIA trial in the Netherlands – an advanced breast cancer study on the CDK4/6 inhibitor palbociclib. “They want to see at least a grade 4 according to MCBS for 1st vs 2nd line therapy, QoL and OS.”

But the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations (EFPIA) have lined up with the EMA in criticising the BMJ paper, saying that the study predominantly focused on clinical trials, rather than on real world data on patient outcomes, and quoting Pignatti saying, “Restricting approvals of cancer medicines only to situations where there is indisputable evidence of improvement in OS or QoL will not improve the outlook for cancer patients in the EU. On the contrary, such an approach may deprive patients of early access to effective medicines for patients in urgent need.”

A greater role for clinicians and patients?

The idea of putting oncologists and patients much more at the centre of how treatments are developed and deployed is perhaps the most important theme that is emerging from the focus on clinical benefit. As de Vries says, there has been the view that doctors take care of patients, and others decide which drugs are available to them. She notes though that in the Netherlands, there is a longstanding committee where oncologists, especially, can decide that certain drugs are not relevant to give to patients.

This may become more usual – oncologists at Sloan Kettering in New York, for example, made the news when they decided they wouldn’t use an expensive new colon cancer drug, although cost was a key factor.

This may well have prompted current moves in the US to follow Europe’s lead in investigating value-based pricing for drugs – the more a drug proves effective for a patient, the more a company can charge. Hartmann, for one, says he is glad that de Vries and colleagues are “bringing back oncologists into the story”.

Involving patients is harder, but a key goal. Pignatti says his main reservation about the current MCBS is that it needs validation with patients to take it forward as a clinical decision-making tool, apart from use in the HTA field. “This scale was never designed for the purpose of clinical decision making and was mainly constructed on the basis of oncologists’ views rather than a systematic evaluation of patient preferences,” he has said.

De Vries says the scale has been welcomed by patient advocacy organisations, and that help from patients will certainly guide future versions of the scale, and cautions that it is still early days – “We only launched the first version in 2015.” The EMA is also investigating whether patients could be part of the regulatory process – for example in a pilot study on patient preferences (Clin Pharmacol Ther 2016, 99:548–54).

Patient advocate, Bettina Ryll, founder of Melanoma Patient Network Europe, who also chairs ESMO’s patient advocates working group, is another who takes issue with the BMJ paper and the general sentiment that too many drugs are poor. “The absence of evidence is not the evidence of absence,” she says.

“In my experience people misunderstand the EMA’s remit, even in the oncology community,” adds Ryll. “It is not about approving drugs that are necessarily better than before, but drugs that are safe and do what they claim to do. We have HTA bodies to decide on their cost-effectiveness.”

Ryll has strong words for the criticism that using surrogate endpoints in trials is not good enough. “These drugs save patients’ lives while on trials. If you go back to the Helsinki Declaration, no interest can take precedence over that of a single research individual, so our first premise for any trial must be to save patients’ lives. This is the reason why we look at PFS or any other surrogate marker, especially in oncology. However, this does not relieve us of the obligation to collect OS data afterwards and in the real world, not in an idealised trial population. There is an ‘ivory tower’ debate about the ‘ideal’ data set, independent of the human cost associated with it, which I find entirely unacceptable.”

“There is an ‘ivory tower’ debate about the ‘ideal’ dataset, independent of the human cost associated with it”

She also points out that the QoL measures are currently too unreliable to draw firm conclusions about lack of benefit (and if there is one point that everyone agrees with, it is that measuring QoL is hard and needs much more work – see also, ‘PROMs put patients at the heart of research and care’).

New drugs such as checkpoint inhibitors do not necessarily behave like the blockbuster chemotherapy drugs of old, she adds, and it is not appropriate to use basic median measures of survival, when a drug such as ipilimumab has big effects in a small group (as Tannock also points out). “The best drugs can look bad if we don’t treat them differently.” She also cautions against judging drugs in isolation: “We need a long-term strategy for survival, as we see now in melanoma where patients cycle between different therapies. Taking a drug out of a treatment landscape can risk the entire enterprise.”

Collecting real world data is the answer

The critical stage for Ryll is generating data on drugs when they are in the clinic. “It’s an evidence collection problem – the regulators won’t fix that for us,” she says, adding that she supports the adaptive approach and a move away from traditional RCTs – “We need an approach that enables both access and systematic learning, especially in situations of high unmet need.

“Also, I have people in my melanoma group who simply can’t believe it is even ethical to randomise people; today’s patients are way better informed and less willing to passively accept what is considered as ‘research’ by others.”

A good example of the way forward, she comments, is the Dutch Melanoma Treatment Registry, set up in 2013 to track the treatments given to all patients with advanced melanoma in the Netherlands (see EJC 2017, 72:156–65).

“It’s an evidence collection problem – the regulators won’t fix that for us”

Ryll and advocate colleagues have run a workshop on the MCBS – she likes the tool as it provides a systematic way to evaluate clinical benefit independent of price. But, as she points out, it works best with mature data sets. “So it is weakest when we need it most, namely in situations of uncertainty, as it is reliant on RCTs. Patients often have to make decisions before that data becomes available, and don’t have the luxury to wait. It is still a valuable way of thinking, but I believe we need different approaches to bridge this evidence gap.”

De Vries points out that a recent MCBS revision does include single-arm studies aimed at orphan diseases and diseases with high unmet need. She notes also that MCBS can be used as educational tool to help oncologists interpret data from clinical trials and in journal club discussions regarding the efficacy of new treatments. (One of the big issues in the drug debate is indeed about understanding the clinical applicability of the trial results – if most oncologists don’t understand hazard ratios, what chance for patients?)

There is probably no solution to all of the problems in trying to rank clinical benefit, as Alberto Sobrero, an Italian medical oncologist who has been on the MCBS taskforce, notes in an ESMO Award presentation (ESMO Open – 2017, 2(1):e000157). For example: “A prohibitive task in oncology is finding equivalences between extent of benefit in terms of OS and … other endpoints such as PFS.” Clinical benefit is also an integration between efficacy, toxicity and what he calls ‘convenience’ – trips to hospital, ability to work, etc. Above all, tools need to have a “sound scientific basis, something as close as possible to what patients value most and something easily understandable by all other stakeholders.” But he believes the MCBS and other tools are a good start.

If it is true that the current system is not sustainable, the way forward seems to be for a much more open debate about the uncertainties and choices among all parties, as Pignatti advocates, while bringing tools such as MCBS to bear, with the eye on improving trial design and biomarkers.

“The way forward seems to be for a much more open debate about the uncertainties and choice among all parties”

But the key tension between the regulators and their supporters, and critics such as Prasad, looks set to continue. “It is only because regulators are lax that payers have had to wield the stick,” Prasad has said. “The default path to market for all cancer drugs should include rigorous testing against the best standard of care in randomised trials powered to rule in or rule out a clinically meaningful difference in patient-centred outcomes in a representative population.”

At stake though is also speed. It can’t be right that abiraterone, for example, took some 20 years to enter clinical practice, and as an academically developed drug it could – and should – be far cheaper, which implies a different sort of regulation or industrial policy.

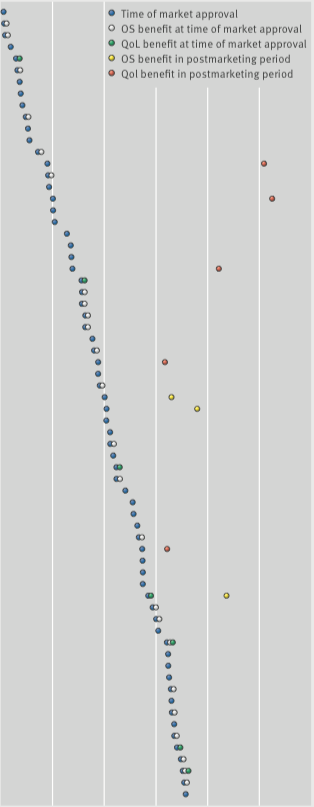

Overall survival and QoL: what we know

From 2009 to 2013, the European Medicines Agency approved 48 cancer drugs for 68 indications. Of the 44 drug indications that did not show a survival benefit at time of approval, and with a median of 5.4 years’ follow up (3.3–8.1 yrs), three (7%) were subsequently shown to extend life after market entry, and five (11%) were associated with some improvements in quality of life.

The figure was adapted (details of agents and indications excluded) from C Davis et al. (2017) BMJ 359:bmj.j4530, and reprinted under a Creative Commons licence. Details of the agents and indications referred to in this figure can be found in the original (open access) article.

Leave a Reply