Competitor drugs entering the market are opening opportunities to make important savings on an increasing number of biological anticancer agents. But, as Rachel Brazil reports, many countries, including those with the most stretched health budgets, could do a lot more to reap the potential rewards.

The promise of cheaper biological drugs is now coming to fruition in oncology. Biosimilars for supportive therapies used in oncology have been available in Europe for over a decade. Over recent years, biosimilars of key monoclonal antibody (mAb) anticancer treatments have also become available, including for trastuzumab, used to treat HER2+ breast cancer (reference drug, Herceptin), bevacizumab, used to treat colon and lung cancer, as well as glioblastoma and renal-cell carcinoma (reference drug, Avastin), and rituximab, used to treat some B-cell lymphomas (reference drug, Rituxan).

At least a further eight oncology biologics will come off patent in the next four years, bringing cheaper prices, with the hope of investing the savings in treating more patients and increasing access to other therapies.

So far biosimilar take-up has not been uniform across Europe. Some countries are already reaping the benefits, whilst others ‒ including many countries with the most stretched health budgets ‒ are yet to do so.

Switching has led to big savings

In September 2019 the UK’s National Health Service (NHS) announced it had saved £294 m (€340m) from its drug budget in 2019 and a total of £707 m (€820m) over the two-year period 2018‒2019. The biggest saving (£110m ‒ €127m) came from switching to biosimilars of Humira (adalimumab) ‒ a medicine used to treat inflammatory conditions.

In another recent analysis, looking at the economic impact of switching to trastuzumab and rituximab biosimilars, an Italian team evaluated five phase II trials including 2,362 patients being treated for advanced breast cancer or follicular lymphoma. They found the economic advantage of biosimilars amounted to €274 per month for rituximab and €3,283‒€6,310 per month for trastuzumab, up to the time of treatment failure, which represented a 40% saving on the cost of the originator drugs (Anticancer Res 2019, 39:3971‒73).

A recently published analysis suggested that Europe as a whole could save between €0.91 bn and €2.27bn over the next five years by switching to trastuzumab biosimilars (BioDrugs 2019, 33:423‒36). A separate budget impact analysis, focused just on Croatia, showed that switching to a trastuzumab biosimilar could save between €0.26m and €0.69m ‒ representing a saving of between 15% and 35%. Reinvesting this amount, the study found, would make it possible to give the treatment to an additional 14‒47 patients per year (Appl Health Econ Health Policy 2017, 15:277‒86).

Switching has increased access in some cases

Decreasing prices has in some cases brought increased access, says Adrian van den Hoven, Director General of Medicines for Europe, the organisation representing Europe’s generic and biosimilar medicines industries. Use of filgrastim, the growth factor that stimulates white blood cell production, was heavily restricted in Europe until the arrival of biosimilar. You really had to be diagnosed with severe neutropenia before you could get access to this product.” Today in the UK, he says, with access to biosimilars costing around 30‒40% less, “they [have] allowed doctors to prescribe this for preventive use.” In some countries, such as the southern healthcare region in Sweden, use of filgrastim has increased five-fold (Future Oncol 2019, 15:1525‒33). Increased use of almost 435% in Hungary and 515% in Slovakia was also reported by industry sources at the 2019 Biosimilars Commercialisation Summit.

Savings are also being invested

in providing access to novel,

more expensive treatments

In some countries savings are also being invested in providing access to novel, more expensive treatments, which may partly explain why oncologists, in the experience of van den Hoven, have been generally more open to switching than were clinicians working in the more chronic diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, where biosimilars were introduced earlier. “The acceptance and the willingness of clinician to use biosimilars has been much faster in the area of oncology, for first-line and second-line treatments,” he says.

Big differences in take up across Europe

That rapid take up applies to some countries much more than others, however, according to Paul Cornes, an oncologist from Bristol, in the UK, and part of the Comparative Outcomes Group ‒ a research cooperative interested in healthcare value. And it is some ‒ but by no means all ‒ of the richer countries that seem to be leading the way. “The biggest uptake [and] the greatest economic benefits appear to be in the UK and the Nordic countries, and increasingly Germany.”

A recent study on the take-up rate of rituximab biosimilars for treating patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma, for instance, showed big differences across the so-called EU5 countries (France, Germany, Italy, Spain, UK). Approved in Europe in early 2017, prescription rates averaged across the five countries increased from 7% to 35% between July 2017 and September 2018. But there were important differences between countries. For patients treated with a rituximab-including regimen, prescribing of any EMA-approved rituximab biosimilar in the third quarter of 2018 was 72% in Germany and 63% in UK, while France, Italy and Spain reported 47%, 32% and 30% respectively (JCO 2019, 37:15 suppl, e19054).

In Scandinavia, where biosimilars are strongly promoted by health authorities, the fast uptake contrasts with countries like Italy, where health authorities have had a more conservative approach. Cornes believes it’s the result of entrenched differences in attitudes to healthcare and the extent to which it is seen as a communal responsibility that must be nurtured. “[In the UK] there’s a kind of awareness that you have to save where you can,” says Cornes. “They do revere their health services and they joke that the NHS is a religion.”

Where we have the biggest problems is actually

in the poorest countries of Europe

“Where we have the biggest problems is actually in the poorest countries of Europe ‒ Romania [and] Bulgaria,” says van den Hoven. “They have been very slow to get their machinery in order to incentivise the use of biosimilars, and so they don’t benefit from the competition. Those are probably the countries that need this the most. A lot of patients don’t have access to those biologics today.”

He mentions the example of the hospital tender for trastuzumab in Romania, where he says, “the incumbent [i.e. Roche, which produces Herceptin] was able to get a tender issued one month before the biosimilars entered the market. So obviously, it was the only supplier and so it won a tender before the biosimilars could even compete… until the next round of tenders.”

Medicines for Europe has set up a task force to help these countries improve their uptake.

Clinicians need confidence in biosimilars

Part of the issue is clinicians’ attitudes to biosimilars, and their willingness to prescribe them. A 2017 survey on knowledge and use of biosimilars, conducted by ESMO (the European Society for Medical Oncology) amongst 393 oncologists, showed that only 49% of them used biosimilars in clinical practice (ESMO Open 2019, 4:e000460). “It’s difficult to say why only half are using them, given what we know… I hope the rate is higher now,” says Giuliani, one of the co-authors.

Uncertainty about the safety of switching was certainly a factor contributing to initial reluctance with some oncologists. But, as Cornes says, “These are not under-tested drugs. The European regulators spend a year reviewing 60‒100 tests of comparability, and we hear that they’re reviewing 10,000 pages of data, and the volume of data and the time they take to review it is exactly the same as a brand new drug.”

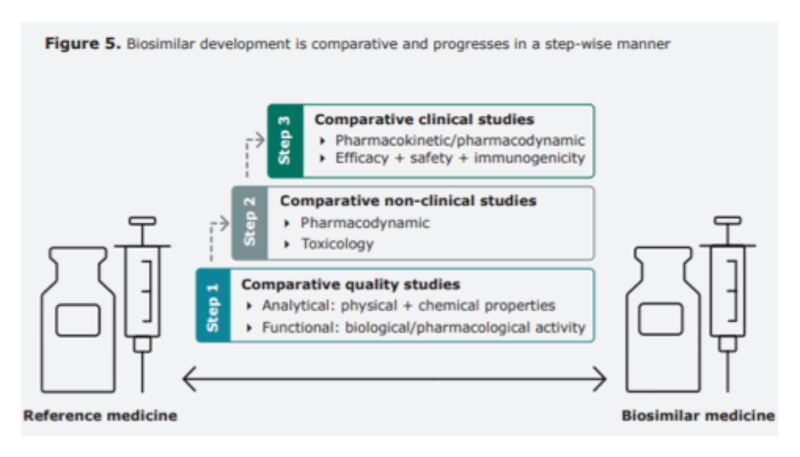

The different drug registration pathway for biosimilars

could be one reason for hesitation

The different drug registration pathway for biosimilars could be one reason for hesitation among some clinicians. “We are used to phase I, II and III clinical trials ‒ we need to move our ‘angle of observation’,” says Giuliani. The ESMO survey showed that clinicians were still paying a lot of attention to clinical data rather than the evidence demonstrating biosimilarity to the reference drug. Hillel Cohen, executive director of scientific affairs at Sandoz in Princeton, New Jersey, agrees that lack of familiarity with the biosimilar regulatory pathway, is an issue with some practitioners, “especially the reliance on analytics, and not large-scale, clinical safety and efficacy studies that physicians have been trained to look at.” He believes, however, that this is changing over time “We’ve seen that as clinicians are getting more experienced using biosimilars, and it’s certainly true in Europe, these concerns seem to diminish.”

Biosimilars ‒ pathway to regulatory approval

Early in their history, the potential safety and efficacy impact of switching a patient from a reference product to a biosimilar was heavily debated, but as the drugs have been used by more patients and for longer, confidence has grown thanks to convincing evidence from large number of studies.

In 2018 Cohen and co-authors published a review of more than 90 studies looking at this evidence. “These enrolled over 14,000 patients, seven different molecules, including oncology products, in 16 different disease locations,” says Cohen. “It provided reassurance to healthcare professionals and the public that the risk of immunogenicity-related safety concerns or diminished efficacy is unchanged after switching… no review today has revealed any reason to be concerned after switching from a reference product to a biosimilar.”

Extensive education campaigns carried out by many organisations have helped convince the clinical community. “Peer-to-peer initiatives in education are very influential,” says Cohen. Cornes agrees that education initiatives carried out in preparation for the release of oncology biosimilars has had a big impact, and he credits the European regulators with playing a crucial role in supporting and explaining their process.

The approach taken by patient advocacy groups has generally stressed the importance of ensuring patients are fully informed about any changes in their prescriptions from reference drug to biosimilar, or between biosimilars, and that they are able to discuss changes with their clinicians and know what to ask (see for instance the biosimilars toolkit of the International Alliance of Patients Organizations www.iapo.org.uk/biosimilars-toolkit).

Clinicians need an incentive to switch

Take-up of biosimilars is not down to education alone, however. “[Physicians] have to have an incentive to do so,” argues Cornes. Different countries have used a variety of carrot and/or stick approaches, he says.

Denmark used an aggressive approach to push physicians to prescribe the first biosimilar, infliximab, used since 2014 to treat a number of autoimmune diseases. “They basically said you will use the biosimilar unless the doctor can produce clinically supportable evidence as to why that’s the wrong action.” While that approach had the intended effect, says Cornes ‒ “In a matter of a few months, Denmark switched more than 80% of their patients,” ‒ it also caused “some friction between managers and healthcare professionals,” according to ESMO’s Giuliani.

Sweden, meanwhile, adopted a slightly more consensual approach, which also worked. Clinicians faced no initial obligation, and early uptake was slower. But by 2016, when confidence had been built, patients were informed of a switch by letter, and within four months 90% of them were using a biosimilar (ESMO Open 2018, 3:e000420).

The savings were invested back into clinical services,

creating a win‒win situation

In the UK incentives have been offered whereby the prescribing authorities benefit from the savings made from switching to biosimilars, using a ‘gain share’ model. A well-publicised example relates to University Hospital Southampton and their local Clinical Commissioning Group. When they switched to infliximab biosimilars, the cost savings were divided between the hospital and commissioning group, which then invested the money back into clinical services, creating a win‒win situation.

To achieve this switch, says Cornes, they invested in specialist drug optimisation pharmacists. “An investment in a year’s salary for a pharmacist was paid back in about a month with the money generated by saving. And [it] indicated that people with knowledge of [biosimilar] drugs, who had the time and ability to talk to patients, could give them the confidence to swap.”

The NHS now aims to have 90% of new patients being on the best-value biological medicine within three months of product launch, and 80% of existing patients within 12 months. The first UK oncology biosimilar, rituximab, launched in April 2017, reached this target within 5 months.

Savings vary according to payer purchasing mechanisms

Another factor that varies between countries is the payer purchasing mechanisms used. A report commissioned by Pfizer from IQVIA Institute for Human Data Science found evidence that, at a hospital level, the use of single-winner contract tenders led to rapid biosimilar uptake, with biosimilar volume share reaching 80% in less than six months bit.ly/IQVIA-Biosimilars. However, it also points to evidence that multiple-winner contract tenders may result in lower costs at a regional level (measured by average net molecule costs per defined daily dose), because reductions are obtained on multiple products, often including the originator drug (ibid).

Balancing savings with ensuring a sustainable supply

The UK model is praised by van den Hoven for encouraging competition, but avoiding the pitfalls that in some instances have led to drug shortages. “They’ve organised the tendering for biosimilars to ensure that they have at least three or possibly four different suppliers, including the incumbent maybe in some cases, and that way, they make sure that they always have a guarantee of supply,” he says.

Patent expiry dates for oncology biologicals

Biologic Approval date (EU) Estimated patent expiry date (EU) Catumaxomab (Removab; Neovii) Used to treat malignant ascites, a condition occurring in people with metastasising cancer.

April 2009

May 2020

Trastuzumab emtansine (Kadcyla; Genentech) Used to treat HER2+ breast cancer that has come back or spread to other parts of the body.

November 2013

June 2020

Alemtuzumab (Lemtrada; Sanofi) Used to treat chronic lymphocytic leukaemia and multiple sclerosis. In CLL has been used as both a first-line and second-line treatment. In MS it is generally only recommended if other treatments have not worked.

September 2003

May 2021

Ipilimumab (Yervoy; Bristol-Myers Squibb) Used to treat advanced melanoma

July 2011

December 2021

Denosumab (Prolia/Xgeva; Amgen) Used to treat osteoporosis, treatment-induced bone loss, metastases to bone, and giant cell tumour of bone.

May 2010

June 2022

Pertuzumab (Perjeta; Genentech) Used in combination with trastuzumab and docetaxel for the treatment of metastatic HER2+ breast cancer; also used in the same combination as a neoadjuvant in early HER2+ breast cancer.

March 2013

March 2023

Ramucirumab (Cyramza; Eli Lilly and co.) developed for the treatment of solid tumors. December 2014

May 2023

Brentuximab (Adcetris; Takeda) Used to treat relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma and systemic anaplastic large cell lymphoma

October 2012

August 2023

Maintaining a healthy biosimilars market may not be down to Europe alone, however. The US regulators, the FDA, approved their first monoclonal antibody biosimilar in 2016, and now there are two or more biosimilars on the market for each of the cancer therapies bevacizumab, trastuzumab and rituximab. But some are questioning how sustainable the US biosimilars market will be, with drug companies creating ‘patent thickets’ to protect their monopolies through new formulations and delivery methods.

This year Pfizer announced it had abandoned five of its pre-clinical biosimilar programmes. “There’s a lot of pessimism,’ says Cornes. ‘I can see that a lack of traction in the American market, for whatever reason, is going to cause trouble for Europe.”

Speaking from the perspective of the European biosimilar medicines industry, van den Hoven warns that, “There is a concern from our side of the industry with the sustainability, longer term, because as the prices are pushed quite low, there’s an issue of how sustainable this is… We’re concerned that companies will focus more on [high-volume]biologics and less on some of the niche biologics for orphan diseases, because there’s no real incentive.”

“Do we just take the lowest [price],

or do we think what does it take to nurture a market?”

Biosimilars certainly need considerably higher levels of investment than generics ‒ one estimate is that it takes seven to eight years to develop a biosimilar, at a cost of between $100m and $250m, making them very vulnerable to low or anti-competitive pricing (Am Health Drug Benefits 2013, 6:469–78). Cornes says purchasers have got to consider the issue of sustainability: ‘Do we just drop the price and take the lowest one, or do we think what does it take to nurture a market so these companies will be here in 10, 20, or 30 years from now?”

One area that adds to the cost is the large amount of data required by the regulators, which van den Hoven says could be streamlined. ‘We’ve been saying for some time now, we need to look at what is the purpose of all these clinical studies. There have been some small improvements. For example, in Europe, they have reduced the number of animal studies that the industry has to do.” Currently clinical studies also have to be carried out separately for each regulator, rather than being able to use the same data, which all adds to development costs. “We’ve made incremental progress[in discussions with the EMA], but I think we could do a lot more,” he says.

Cohen is still positive about the future for biosimilars. “There’s no question that the number of biosimilar oncology drugs will increase, has increased, and is increasing, both in supportive and treatment settings,” he says. Certainly lessons have been learned since the first oncology biosimilars were introduced ten years ago. “The difference is nowadays communication is better and we understand the scepticism and can explain [biosimilar regulation pathways],’ says Giuliani. The question is how to turn those lessons into policies across Europe that can maximise the benefits for all.

Leave a Reply